The Name ‘America’ and Amerigo Vespucci March 22, 2013

Author: Beach Combing | in : Medieval, Modern , trackbackThere are perhaps a score of different theories as to where the word ‘America’ comes from. These range from various Amerindian etymologies to a Bristol-based merchant with the surname Ameryk! The theory which enjoys the greatest prestige though is that America is based on a feminised Latin version of Amerigo, as in Amerigo Vespucci, the Florentine navigator of the late fifteenth, early sixteenth century. The argument for Amerigo as the origin of America is strong, so strong that it is perhaps surprising that anyone else has managed to get their voice heard. We rehearse it here by way of a challenge in case anyone out there would like to make a contrary case: drbeachcombingATyahooDOTcom Breezing through the internet this morning the lack of a full description of the case for Amerigo has also been striking.

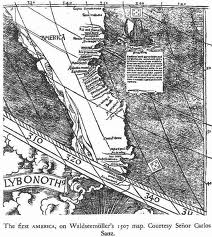

In 1507 in Waldseemüller’s Universalis Cosmographia, one of the first world maps to include the Americas (as opposed to attempts to assimilate the newly-discovered territories with Asia), the word America appears hovering over what is apparently Brazil (see above). In fact, in a later edition of this map ‘Brazil’ would actually take America’s place. Of course, the appearance of ‘America’ on a map in 1507 need not lead us directly to Amerigo Vespucci, though he had been active in the previous years. But consider the following four facts that do closely tie Amerigo to Waldseemüller’s map.

i) The map is headed by two heroes of exploration. Ptolemy the antique Greek geographer whose rediscovered world map had excited so much Renaissance speculation and map-making; and Amerigo Vespucci himself (below), who is credited with having understood that there was another continent between Europe and Asia. Vespucci may or may not have deserved that credit – Beach tends to think that he did, not least on the evidence of Waldseemüller – but here he is offered up to us as a navigator hero.

ii) There is the hint here that one of the authors had special knowledge of AV. Next to Vespucci’s portrait is a wasp flying in the background: Vespa in Italian (as in Vespucci) is ‘wasp’. Some German scholar, one of Waldseemüller’ team, is punning on Italian in exactly the same way that Vespucci’s family did: the Vespuccis included the wasp on their coat of arms. Unfortunately this is not visible on any version of the map online. It is there though, we’ve seen it with our own eyes on a facsimile.

iii) Between Central America and Argentina Waldseemüller includes a series of Italianate names that come from one of Vespucci’s trips into the ocean. Scholars are uncertain as to how many trips Vespucci made but there is no question that Waldseemüller is borrowing from Vespucci’s work: though possibly at third or fourth hand. There is much debate about how Vespuccian some of Vespucci’s letters actually are.

iv) In the Cosomographiae, a printed work accompanying the publication of the map, there appears the following sentence: ab Americo Inventore …quasi Americi terram sive Americam. From its discoverer Amerigo… so it is the Land of Amerigo or America. All other theories butt their heads hard against this very explicit Christening of the Americas (or rather Brazil).

So we have a map written within five, perhaps within three years of Vespucci’s last voyage across the Atlantic: there is much debate about how many voyages Vespucci undertook hence the uncertainty. That map puts Vespucci at its very centre, in terms of the portrait it includes and in terms too of the name ‘America’.

Is there any way, even out of sheer perversity, to argue that the word America did not actually come from Amerigo? The only way forward would be to claim that the name America had already been adopted by sea-goers to describe the new lands (or part of the new lands) to the west. Waldseemüller and his team knew this and they decided to explain the name in such a way as to honour Vespucci, who coincidentally had a similar first name. If this had been the case though, it would have been difficult to get rid of the name America, hovering over Brazil, from a later edition of said map. Yet that is just what Waldseemüller does…

Two final thoughts. First, Vespucci died in 1512 in Spain: his grave is now lost. He may never have seen the Waldseemüller map (produced on the other side of Europe) and he very likely had no idea that a part of the globe was being named after him: not least because it took a couple of decades for the name to become established.

Second, the Americas desperately needed a European name and it was only a matter of time before Europeans stopped saying ‘the New Lands’. What else was on offer? Well the Columbas was one obvious possibility. However, what about the solution of the Maggioli map of 1504/1505 which suggested the Terra di Gonsalvo Coigi (the Land of Goncalo Coelho)? Coelho had been the commander of one of Vespucci’s voyages. How does the Coigs sound for what we today call the Americas?!