German Crusaders lost in Central Asia? June 29, 2010

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary, Medieval , trackback Beachcombing often stretches himself pretty thin in covering the centuries and sometimes he just doesn’t have the languages to check up properly on a story. With these caveats he offers his readers the following tale that reads like a late Victorian or Edwardian boy’s own adventure.

Beachcombing often stretches himself pretty thin in covering the centuries and sometimes he just doesn’t have the languages to check up properly on a story. With these caveats he offers his readers the following tale that reads like a late Victorian or Edwardian boy’s own adventure.

The text comes from Richard Halliburton’s Seven League Boots, a fun collection of essays on the author’s jaunts in various countries in the 1930s. Things start getting a little trippy on p. 162 with a chapter entitled ‘The Last of the Crusaders’. Beachcombing wants to know: can there be any truth in what the Tennessee author has written here? drbeachcombingATyahooDOTcom For the record, he’s betting on serious misperception or, just possibly, a practical joke on Halliburton’s part. Was Halliburton even trying to cover up for sexual dalliances with his friendly German photographer Fritz in an out of the way corner of the Soviet Union? A pocket size Russian dictionary to anyone who can get to the bottom of this.

…in the spring of 1915, some months after Russia’s declaration of war against Turkey, a band of twelfth-century Crusaders, covered from head to foot in rusty chain armour and carrying shields and broad-swords came riding on horseback down the main avenue [of Tiflis]. People’s eyes almost popped out of their heads. Obviously this was no cinema company going on location. These were Crusaders – or their ghosts.

The incredible troop clanked up to the governor’s palace. ‘Where’s the war?’ They asked. ‘We hear there’s a war’.

They had heard in April 1915 that there was a war. It had been declared in September 1914. The news took seven months to reach the last of the Crusaders…

One of the most curious and romantic legends of the Caucasus tells the story of the origin of this armoured tribe. And as yet no historian has found any reason to believe that the legend is not based entirely on fact. The story declares that this race came, eight hundred years ago, from Lorraine, more than two thousand miles away. The argument is borne out by the fact that their chain armour is in the French style, while their otherwise incomprehensible speech still contains six or eight good German words.

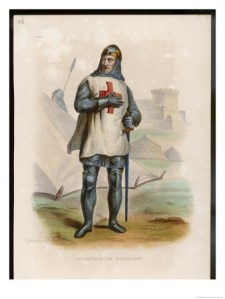

When they left Lorraine, so goes the legend, the last thing they had in mind was the colonization of the frosty peaks of the Caucasus Mountains, for they were followers of Godfrey de Bouillon and planned to wrest the Holy Sepulchre from the Moslem infidels.

But during thee thousand-mile march across what is now Asiatic Turkey, this particular band of Crusaders somehow got detached from the main army, and were prevented by the Saracens from rejoining it. Whether they took a northern course of their own accord, and continued on across Armenia and Georgia to the Caucasus as pioneers, or whether they were fleeing for the lives with Moslem scimitars swishing around their ears, the legend does not say. But we do know that they called a halt in one of the most rugged and unapproachable corners of the Caucasus… and didn’t emerge again in force till 1915 when the rumours of a worthwhile war brought them wearing their ancestors’ coats of mail into Tiflis.

These strange people, called Khevsoors [Ed. Khevsureti], have continued to occupy their hidden corner for over eight centuries. But not one inch have they advanced in general culture. In fact, they have lost whatever of the arts they brought with them from Lorraine, and nearly all the crafts.

Only the Crusader chain armour, more or less indestructible they still have, and the letters A.M.D. – Ave Mater Dei, the motto of the Crusaders – carved on their shields, and the Crusader crosses which adorn the handles of their broadswords and are embroidered in a dozen places on their home-made garments…

Halliburton goes to stay with the Khevsureti and describes a – Beachcombing hopes that any Khevsureti readers will forgive him – rather anti-social, violent Caucasus people who had suits of armour hanging around their houses and liked duelling, drinking and feuding. None of the proof that Halliburton offers apart from perhaps the suits of armour is particularly crusader-like though.

As to the Khevsureti’s fate… Well, if this is not all a great April Fool from Halliburton, and Beachcombing wouldn’t put it past that renegade, then there is a clue at the end. Halliburton dreams of waking up in the Khevsureti village to find Godfrey of Bouillon or Richard the Lion Heart. However, soon after dawn the author bumped into the local ‘agent of the Bolsheviks, who had been established here to save the Khevsoorians from Capitalism’.

‘[The agent] said it was a lot of nonsense looking for Godfrey de Bouillon and King Richard – they were counter-revolutionary Christians and would be liquidated if they set foot in Sovietized Caucasia… and anyway the Holy Sepulchre wasn’t at Jerusalem any more. It was a red granite tomb beside the Kremlin wall in Red Square at Moscow… He said he planned to collectivize these Crusaders on one big farm where they could learn to recite Karl Marx.

Siberia anyone?

***

Beachcombing was incredibly lucky to get two extensive emails from Alexander Bainbridge (30/6/2010), a Caucasus expert whose site is running over with embarrassing quantities of Caucasus material and fabulous photographs – thanks Alex!.

’I seem to remember that both Lev Nussimbaum’s Twelve Secrets of the Caucasus (Nash & Grayson, 1931) and George Milkomane’s Valley of the Forgotten People (London, Faber & Faber, 1941) relate the romantic legend of the Khevsurs being descendants of European Crusaders. (Lev Nussimbaum published his book under the pseudonym ‘Essad Bey’, and George Milkomane under the pseudonym ‘George Sava’.) The legend is, however, pure nonsense, but nonetheless very fun to read. The link between the Khevsurs and the Crusaders seems to have begun with the arrival of the first European travellers and scientists in the Caucasus in the nineteenth century, and is based upon the (perfectly true) fact that the Khevsurs went into battle wearing chain-mail hauberks that went down to their waist and that their clothes, weapons, homes, &c. were decorated with crosses. The curious and romantic, picturesque-seeking nineteenth century took care of the rest, and the Khevsurs were introduced to readers as the descendants of Frankish Crusaders who somehow ended up settling in several valleys of the central Caucasus after having lost their way during their journey to the Holy Lands (despite the fact that the Caucasus is most certainly not on the way to Jerusalem, and that there never was any evidence to support this outlandish affirmation). The Khevsurs’ religion is a blend of Caucasian mountain paganism and (Orthodox Georgian) Christianity, and these Georgian tribesmen though of themselves as the Christians par excellence, guarding Christian Georgia’s northern mountainous border against the predations of the Muslim North Caucasian tribes. The Cross (Georgian: ჯვარი, “jvari”) remains a powerful and respected symbol among the Georgian mountaineers to this day, and its symbolism has permeated their societies and environment. (Many toponyms, for example, include the word “cross” – such as the “[Mountain] Pass of the Bear-Cross”, &c.)’

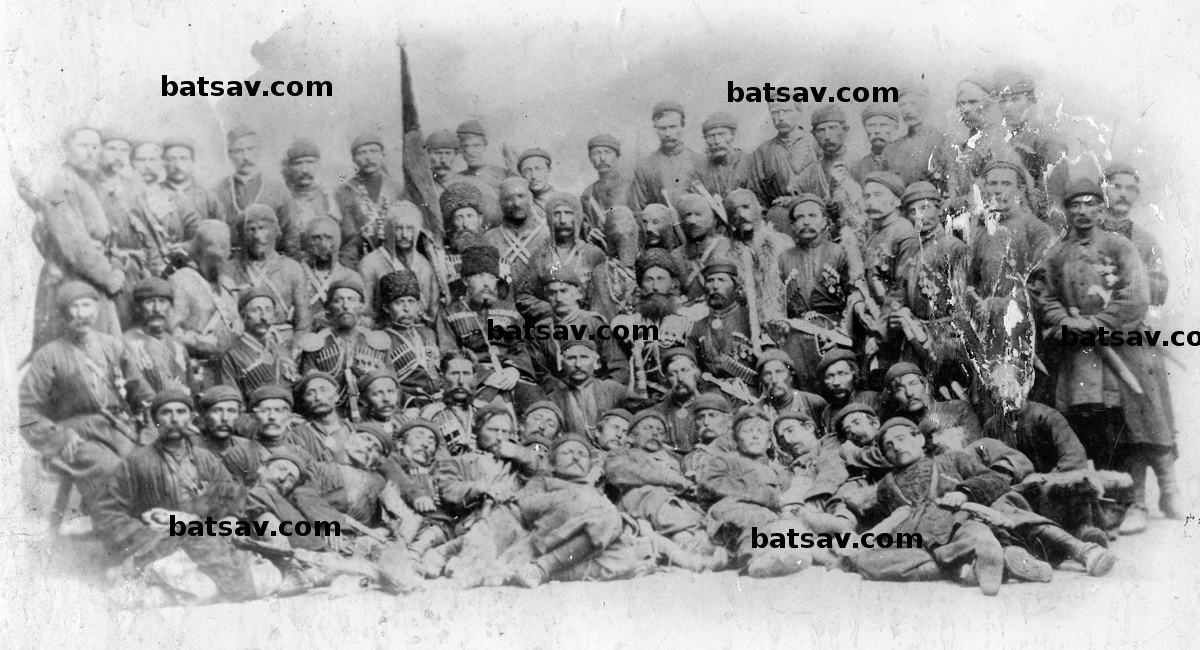

Then as far as the idea of the Khevsurs turning up in Tiflis, AB writes: ‘It strikes me that it is quite possible that this event really took place. Many Georgian mountaineers – whose forefathers had been fighting against Muslim tribes for centuries, and whose descendants were therefore keen to aid the Russians in their fight against the Turks – did actually fight alongside the Russians. The Khevsurs, Pshavs and Tush certainly did, as numerous testimonies and photographs prove. Given that the first motorable road up the remote valleys of Khevsureti was only built in the early 1930s and that the region is still largely inaccessible in winter to this day, news of the declaration of war of September 1914 would indeed have had to wait until the Spring of 1915 to reach the Khevsurs. To my mind it is perfectly possible (and indeed quite likely) that such news would have galvanized many Khevsur warriors into riding down to the Russian viceroy’s palace in Tbilisi [BC’s Tiflis] to offer their aid in the fight against the Turks.’

And if this wasn’t enough AB generously sends some quite superb photographs along. The first shows the Khevsurs wearing chain-mail over their traditional costumes. The second a Khevsur military set up. The third photograph, meanwhile, shows another Caucusus people, the Tush, in battle order in the Russian army! Extraordinary.

Beachcombing has to admit that he was over-sceptical here. He is ashamed now to remember that he actually played around with the word Khevsoor to see if it was an anagram created by Halliburton! He feels, in fact, that his comments about Halliburton were quite unworthy. Apologies to the Tennessee journalist and particularly to Fritz (though Beachcombing still has his suspicions about their ‘dalliances’…). What we have here is a Caucasus people realigning their identity along the lines suggested by European visitors. The Falasha of Ethiopia (‘Africa’s Jews’) are arguably another case of this and one that Beachcombing hopes to visit in the not so distant future.