Ten Thousand Romans in Turkmenistan September 19, 2010

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient , trackback There are many reasons for which individuals have travelled a long way from home in history: money, love, fear… But a vitally important and generally overlooked motive is imprisonment. Soldiers taken in battle have often (and very sensibly) been moved from where they were captured to the furthest possible point from their own country to avoid escape attempts.

There are many reasons for which individuals have travelled a long way from home in history: money, love, fear… But a vitally important and generally overlooked motive is imprisonment. Soldiers taken in battle have often (and very sensibly) been moved from where they were captured to the furthest possible point from their own country to avoid escape attempts.

Now if a free-fighting Dutchman was caught by the Belgians in the early nineteenth-century then he would have been marched a couple of hundred of miles south to the borders with France. But if a German tribal warrior was caught on the Rhine in the second century AD by the Romans then he could end up being walked thousands of miles into captivity to guard, say, a tower on the Red Sea.

It happened… Beachcombing has a bulging file.

Certainly, the mechanics of prisoner displacement explain our best evidence for Romans in deepest Asia. In 53 B.C. the Romans met the Persians at the Battle of Carrhae. There a Roman army numbering over forty thousand was pinioned by Persia’s archers and slowly annihilated in the terrible deserts of northern Syria.

‘When Carrhae battle fatally was struck, And all our princes captiv’d by the hand’, as Shakespeare might have put it.

The Romans’ leader, the insufferable Crassus, had molten gold poured down his throat – or so a suspiciously Roman-sounding legend tells us. But several thousand other Roman soldiers were captured – perhaps ten thousand – and marched off to the other side of Parthia where they paid for their lives with service to the great Surena, defending Parthia from her eastern enemies.

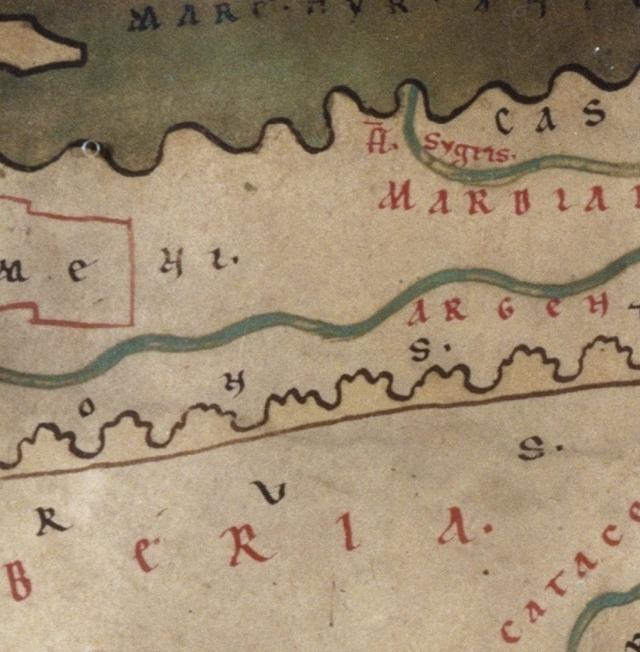

More specifically, Pliny the Elder tells us (NH 6,18) that the prisoners were herded to the country of Margiana (the Persian territory of Margu) ‘well-known for its warm sunny weather’ and fortified by the surrounding Karakum deserts: in modern terms we are in Turkmenistan aka ‘the back of Asian beyond’. It was in this same general area that earlier Persian kings had exiled unreliable Greek elements.

Margiana was not though as barren at it might at first sound. The ancient geographer Strabo, 2,1,14 for one defended it against the charge of lying outside the inhabited world: Strabo may even have relied for his description on returning Roman prisoners.

‘Who, pray, would venture to maintain this, when he hears of men of both ancient and modern times telling about the mild climate and the fertility, first of Northern India, and then of Hyrcania and Aria, and, next in order, of Margiana and Bactriana? For, although all these countries lies next to the northern side of the Taurus Range, and although Bactriana, at least, lies close to the pass that leads over to India, still they enjoy such a happy lot that they must be a very long way off from the uninhabitable part of the earth… And in Margiana, they say, it is oftentimes found that the trunk of the grape-vine can be encircled only by the outstretched arms of two men, and that the cluster of grapes is two cubits long.’

The great sinologist Homer Dubs argued (on one of his rare off days) that Romans from Margiana had ended up in nearby China as mercenaries. Beachcombing will return to this claim, with sceptical relish, towards Christmas: another post another day. But Margiana was certainly a junction on the Silk Road and our brave legionaries from Spain, North Africa and Italy will have come face to face with Han travellers. They also, according to the Roman poet Horace, married local women – though the line may be formulaic.

Beachcombing knows all about Li-kien but if anyone can supply him with any archaeological or other textual evidence for a Mediterranean presence in Margiana he would be most interested. Above all, he seems to remember a Latin sentence on a Roman prisoner exchange programme in the time of Augustus? Drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com