Mayan Blood and Mayan Victims October 8, 2010

Author: Beach Combing | in : Medieval , trackback

Beachcombing has had a bad week and so to perk himself up a little he thought that he would resort to the last strategy of the truly desperate: pity someone who is worse off than himself.

Beachcombing has had a bad week and so to perk himself up a little he thought that he would resort to the last strategy of the truly desperate: pity someone who is worse off than himself.

In this spirit and in continuance of his wcih (‘worst careers in history’) series he has decided to rememeber the misfortunes of the Mayan sacrificial victim, typically enemy soldiers captured in battle.

Of course, the Mayans, as many other peoples, sacrificed victims to their gods. But there was something about Mayan procedures that made the Aztecs remove-heart-from-screaming-victim technique seem like a gently given nip and tuck.

For one thing the Mayans had a thing about blood. Spilling blood was a way of reconnecting with the fertile essences of the universe. It, therefore, made sense to shed blood as often as possible.

This was, in fact, a people – unique in Beachcombing’s knowledge – who actually treated the blood-letting lancet as a sacred tool!

However, if blood was so precious then it also made sense to ration its use.

Say for the sake of argument that a Mayan king, let’s call him Jaguar Big Tooth, caught in battle or ambush another Mayan king, Jaguar Little Tooth.

The blood of Little Tooth was particularly precious and killing Little Tooth in an instant would have been foolish. After all, you get more protein from a cow if you milk it for four or five years before slaughtering it and eating its flesh. In the same way it made sense to torture a Mayan sacrificial victim gradually for months on end.

Of course, it would all end in death: often in the case of enemy warriors in the Mayan basketball courts. But in the intervening period the victim might be expected to give his blood and pain in ritualised meetings with the captor priests and nobles.

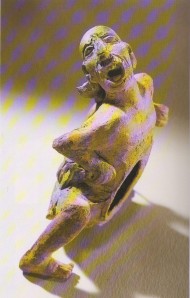

The illustration that Beachcombing has put above is perhaps the most eloquent proof of just how much Mayan victims suffered.

The colour photograph shows the front of a man who is living an orgy of agony. His nose is swollen and broken, presumably from repeated beatings: his face is bloodied. His hands and feet have been knocked out of joint. His scalp has been removed and is hanging off his nape. The hole in his stomach presumably held some Mayan artefact but also represents disembowelling.

The black and white photograph shows the back of the same individual. The scalp is now clearly visible. But there is also tinder tied behind that would have been lit to add to the victim’s misfortunes.

Other statues suggest slicing, breaking of fingers and even castration as variations.

Yikes.

How long did this death of a thousand cuts actually last? Well, there were different categories of prisoner and presumably different rules depending on class and spite.

But in a worse case scenario…

King Paw Jaguar was captured by his enemies in 735. He seems to have been finally killed at a ball game twelve years later: typically he would have been bound into a ball-shape and rolled down a high set of stairs (250).

The intervening decade cannot have been pleasant…

Beachcombing is always open to human sacrifice stories: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

***

Next came a remarkable email from Daniel S – author of an important new blog on Mesoamerica. Daniel gently took Beachcombing to task for his interpretation of disembowelling. ‘During my research with Olmec culture, I came across an interesting phenomenon with their statues. Some Olmec statues (preferably children and women it seems) were made with oversized navals that sometimes went completely through the body. For an example of this, and a direct comparison with a male statue, please have a look at the following pictures: 1, 2 and 3. I couldn’t but remember your pictures of the poor fella with the big hole in his belly, and I wondered if there could be a common symbolism. From what I saw of Olmec figurines, women are sometimes also presented with very wide hips. Naval and wide hip, representing the birth and culture giving power? I know of course, that Olmec and Maya symbolism are very far away from each other, both in time and style. I was wondering, if that element of the naval distributing power however could have passed to the Maya figurine, that you showed us. It would fit to the power-giving blood rites.’ Thanks to Daniel and good luck with your blog!

4 Dec 2010: Daniel over at the Complete Mesoamerica sent in this further email about bellybuttons on Mesoamerican statues – that Beachcombing had originally and probably wrongly understood as disembowelling. ‘Little follow up on our theory, which I told you last time with the Olmec figurines. In the Museum of Anthropology of Xalapa in Veracruz, you can find the sculptures that I’ve attached to this male. watch the Navals, especially the one of the woman to the right… Unfortunately we can’t see the man’s navel here. I have yet to find out to which culture they belong exactly. The form of the eyes look very Olmec to me again.’ Thanks Daniel!!

sent in this further email about bellybuttons on Mesoamerican statues – that Beachcombing had originally and probably wrongly understood as disembowelling. ‘Little follow up on our theory, which I told you last time with the Olmec figurines. In the Museum of Anthropology of Xalapa in Veracruz, you can find the sculptures that I’ve attached to this male. watch the Navals, especially the one of the woman to the right… Unfortunately we can’t see the man’s navel here. I have yet to find out to which culture they belong exactly. The form of the eyes look very Olmec to me again.’ Thanks Daniel!!