Elizabeth Siddal: poets behaving badly October 19, 2010

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackback Beachcombing has a distant day almost constantly in mind – one that he fears tremendously – when little Miss B will arrive home from school prom or a disco or a walk in a wood with an ear-ringed possibly nose-ringed man on her arm, only to announce in dulcet tones: ‘Mum, Dad this is John, he is a poet’. For some reason the profession worries Beachcombing more than the name or the details of his future son-in- law’s hair-style. But, honestly, is there any more career more odious, more appalling, more full of spite than that of the ‘word-smith’? Neurology, mobile phone salesman, post-modern novelist… all pale in comparison.

Beachcombing has a distant day almost constantly in mind – one that he fears tremendously – when little Miss B will arrive home from school prom or a disco or a walk in a wood with an ear-ringed possibly nose-ringed man on her arm, only to announce in dulcet tones: ‘Mum, Dad this is John, he is a poet’. For some reason the profession worries Beachcombing more than the name or the details of his future son-in- law’s hair-style. But, honestly, is there any more career more odious, more appalling, more full of spite than that of the ‘word-smith’? Neurology, mobile phone salesman, post-modern novelist… all pale in comparison.

In any case, in tribute to his daughter’s likely future choice and with his recent review of Edwin Murphy’s After the Funeral in mind [nb EM’s book offer now pasted up there], Beachcombing thought that he would tell the reprehensible story of the poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti (obit 1882) and his ‘muse’ Elizabeth Siddall (obit 1862 and he’ll come back to that spelling in a moment…) Beachcombing should immediately note that it is always a bad sign when the muse dies twenty years before the mused.

DGR was an artist first and a poet second, a man who brought self absorption and morbidity to the levels required by these professions. In his role as an artist he regularly trolled for alluring East End girls to play at being his models. Some of his most striking illustrations include these women, though as the northern ‘dialect’ painter L.S. Lowry noted – Beachcombing would get out the champagne if Little Miss B. came back with Lowry on her arm – Rossetti did not paint women, he painted dreams.

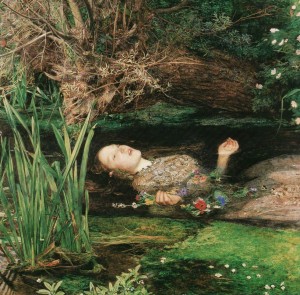

Now Elizabeth. She was a milliner who fell into the clutches of the pre-Raphelite brotherhood, the suspect band of painters and medievalists (ghastly word) which Rossetti had founded. An American member, Walter Deverell discovered her working in a nook of central London and then used her as a model. Later she was paid by Everett Millais to pose as drowned Ophelia. Millais, to his credit, tried to keep her warm in the bath in which she floated with lamps heating it from below. But she nevertheless almost froze and her father later sought compensation for medical bills. It was to be an inauspicious beginning for Elizabeth’s time in the world of high art.

Elizabeth was passed around the pre-Raphelite brotherhood like a piece of merchandise and eventually ended up in DGR’s studio and bed. DGR played Henry Higgins to her Eliza Doolittle and soon she was writing poems and painting pictures herself, works that were admired in rather patronising tones by the illuminati. Beachcombing has never read Elizabeth’s poetry but her pictures are certainly savage and unusual: they suggest a woman who knew herself and rarely compromised.

Sometime around the beginning of her relationship with DGR ‘Siddall’ became ‘Siddal’ perhaps because DGR, an arbiter of taste, decided that it looked more ‘medieval’ or more ‘Anglo-Saxon’? In any case, what DGR had done to the poor girl’s name he was now going to do to her soul.

DGR met Elizabeth in 1850 but only finally got round to marrying her in 1860 after years of living on and off with her. Routine today but downright evil in Victorian times when an unmarried ‘hussy’ was a social pariah in middle class circles. In DGR’s defence (kind of) his family disapproved. The horror!

In any case, in 1861, aged 32, she committed suicide: she had just given birth to a still-born daughter.

Now Beachcombing is obliged to describe DGR’s worst histrionics. In a moment that comes straight out of acting 101, as Elizabeth’s coffin was about to be sealed no less, he placed, in the strands of her long red hair, a notebook of his with many manuscript poems. It took DGR until 1869 to realise that he had made a fatal mistake having lost poems that were both good – some were – and that he could not possibly reproduce from memory. And here the courage which he had lacked to defy his family, he suddenly found to defy the canons of good taste as defined by every human society since the beginning of time: he decided to raid her tomb.

Of course, if this had been Earnest Hemmingway his faux machismo would have demanded that he personally dug up his beloved to retrieve what was his. But – even if there would have been a good poem or two in the experience – the snivelling DGR went by legal routes and had friends exhume the body in the dead of night while DGR was on the other side of capital. The book was retrieved though we learn that a worm had eaten its way through some of the poems making them difficult to read: the crosses that poor DGR had to bear…

Well, Beachcombing feels so much better after getting this off his chest and excuses himself with his readers who turned up wanting the merely bizarre and got the bizarre plus poeisogyny, but it is black day here – rain, the tortoises are still unhappy, Little Miss B insists on watching bad Disney… – and DGR was, let’s face it, a fairly pitiful individual. In fact, the only good thing that Beachcombing can find to say about him was that later in life he adopted some wombats (as you do). The first was called Top and did not live very long. Go figure.

Beachcombing is still looking for unusual corpse stories and anything about poets behaving badly: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com