Rhyming Violence in Early Medieval Ireland October 23, 2010

Author: Beach Combing | in : Medieval , trackback Ireland, the early seventh-century. It is a cold, cold day in late autumn and the monastery is buzzing with excitement. ‘The faminators are coming. There is to be a duel’.

Ireland, the early seventh-century. It is a cold, cold day in late autumn and the monastery is buzzing with excitement. ‘The faminators are coming. There is to be a duel’.

As soon as the master of studies hears the news he waddles off to tell the abbot. It takes him half an hour, but after badgering both from him and the monastic librarian the abbot grumpily agrees. A special holiday is announced and the brothers excitedly leave the holy confines to enjoy the spectacle. Beachcombing can’t resist tagging along too.

Many of the faminators who are arriving for this fight are Irish, but many too are foreign, coming from England, from France even from Spain. However, whatever their nationality, they are all immediately identifiable by their dress; the long red gowns that they wear on their travels through the Irish countryside.

As normal the faminators – the ‘speakers’ literally: wandering scholars that made the most of Ireland’s ancient learning – pay little attention to the monks. Instead, their eyes rest on the contestants. These two men square up to each other, staring fiercely. The master of ceremonies coughs and announces in Latin the reasons for the duel. (The faminator on the left had let it be known that he was a better faminator than the faminator on the right. The faminator on the right could not let this pass and so issued a challenge.) The crowd nods. The master of ceremonies steps back. The ‘famination’ will begin.

It ought to be noted at this point that nothing would have horrified this seventh-century audience more than that one of the faminators should have hit or kicked the other. Violence was practised with alarming frequency in seventh-century Ireland, but faminating was an altogether more subtle art. It was the ‘elegant’ – we will soon see that the faminators had a very strange idea of ‘elegant’ – use of poetic Latin, aimed at your opponent.

The challenger stands up and begins his assault:

I do challenge the adroit wrangler to a verbal duel,

To engage in rhetorical gymnastics with eagerness

For previously I contended against three athletes:

I slaughtered helpless warriors,

Punished powerful peers,

And brought down stouter giants in the fray.

In simple modern English we would write ‘I challenge you to a fight with words. I have already beaten three others in such a fight.’ But the faminators did not believe in saying a ‘fight with words’ when they could instead show off by saying ‘verbal duel’ or ‘rhetorical gymnastics’ – all, of course, in perfect Latin. And it is in this pretentiousness that their special charm is to be found.

The manuscript, in which a record of this duel is recorded, continues in a similar vein:

When [my opponents’] cruel darts [i.e. words] begin to prick me,

Straightaway I unsheave my dextrous sword,

Which hacks up sacred pillars;

I take my wooden shield in hand,

Which compasses my meaty limbs with protection;

I brandish my iron dagger,

Whose deadly tip torments the wheeling archers;

Hence I summon all my peers to the contest.

Then just in case there could be any doubt whatsoever.

This elegant effusion of phrases dazzles,

Since it does not pile up words on a faulty foundation,

But checks its forceful vigour with careful balance.

Do you produce with equal skill a mellifluous flow of Ausonian speech from your vocal chords?

Or let Beachcombing sum up the whole poem so far: ‘I challenge you to a fight with words. I have already beaten three others in such a fight. Your words will not hurt me. Instead I will speak against you with my beautiful phrases. Now do you have such beautiful phrases?’

In Beachcombing’s English it takes forty words: in the faminators we come close to one hundred and fifty. So much for the economy of poetry.

Unfortunately, we have no idea how this particular contest ended. All that is left is this poem in a manuscript and some other similarly convoluted poetry from other competitions between faminators. We cannot even be sure of the English translation of many of these poems. The Latin that the faminators used was extremely Byzantine – passable syntax, absurdly difficult vocabulary – and modern translators admit that many doubts remain.

What for example does ‘the dextrous sword which hacks up sacred pillars’ mean? Beachcombing guesses a pen or tongue that analyses holy scripture.

Then, of course, the literal translation above can do no justice to the poetry in the Latin, a poetry that the Italian medievalist and novelist Umberto Eco has described as being ‘like the sea’. Beachcombing would say that is more like air escaping from a flatulent radiator, but anyway…

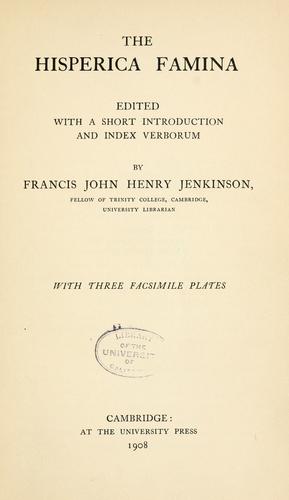

In fact, most of the information that Beachcombing has amassed about the faminators comes not from the brief, few, deliberately difficult poems that survived them in a collection called the Hisperica Famina, but rather from other writers. Our most important source is the English historian Bede who refers to the many foreign scholars who flocked to Ireland in the seventh century in search of wisdom and learning. These scholars, it seems, walked around the island, travelling from teacher to teacher. And these scholars, or at least groups of them, united with a strand of native learning, became the faminators with their word jousts in almost incomprehensible Latin.

However, as learning grew in England in the course of the seventh century the groups travelling to Ireland fell away and the culture of the faminators died. All that is left now are their silly but strangely poignant poems, written on a why-use-only-one-word-when-ten-will-do basis for deadly earnest duels between scholars the details of which we have long since lost.

Any other examples of medieval flyting? drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com