Review: Creative Malady December 13, 2010

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary, Modern , trackbackGeorge Pickering (obit 1980) was, when he wrote his three-hundred-page essay Creative Malady (George Allen and Unwin 1974), a retired Professor of Medicine from the University of London and Master of Pembroke College (Oxford). In his younger days he had worked on headaches, hypertension and peptic ulcers – all illnesses then linked to mental states. And if Beachcombing can hear in his prose a classic NHS mandarin with the smattering of knowledge and arrogance that characterises that type, this unusual background meant that GP was particularly open to the mood-induced aspects of illness. Early on in the book, for example, he describes his encounters with Soldier’s Heart (De Costa’s Condition) a classic anxiety condition that, for too many years, was seen as a straightforward physical disease.

Pickering joined, in his work, the long line of doctors and medical historians who have enjoyed trying to give historical illnesses names: what or who killed Napoloeon/Tutankhamon? Etc etc. He had though a slightly different take, believing that he had traced a larger pattern, in particular the way that many ‘sensitive’ over-achievers in history suffered from self-induced illnesses.

Beachcombing doesn’t normally have much time for ‘mind over matter’. Yet when it comes to the question of the body’s power over itself he has to confess that he is, despite himself, impressed. Take the extraordinary cases of ‘spontaneous healing’ in some forms of cancer. Take the evidence of illness following on from grief and tragedy. Or take the cases of young women with phantom pregnancies lactating.

Even doctors – and not just those with the right background such as Pickering – are aware that mental state is important, slipping in seemingly innocuous questions about ‘how-are-you-feeling’ and holidays.

The placebo/nocebo effect amounts to mind over matter, as do psychosomatic conditions and these are among the pillars of modern medicine.

Yet the mind’s ability to influence the body is difficult to pin down: the intellectual equivalent of nailing jelly to a wall. People working in health care agree that it matters, but no one is quite sure why or how to study the question. Our great, great grandchildren will likely look back and see our fledgling attempts as hopelessly premature, the equivalent of measuring falling objects from Renaissance towers by counting the chiming of a church bell.

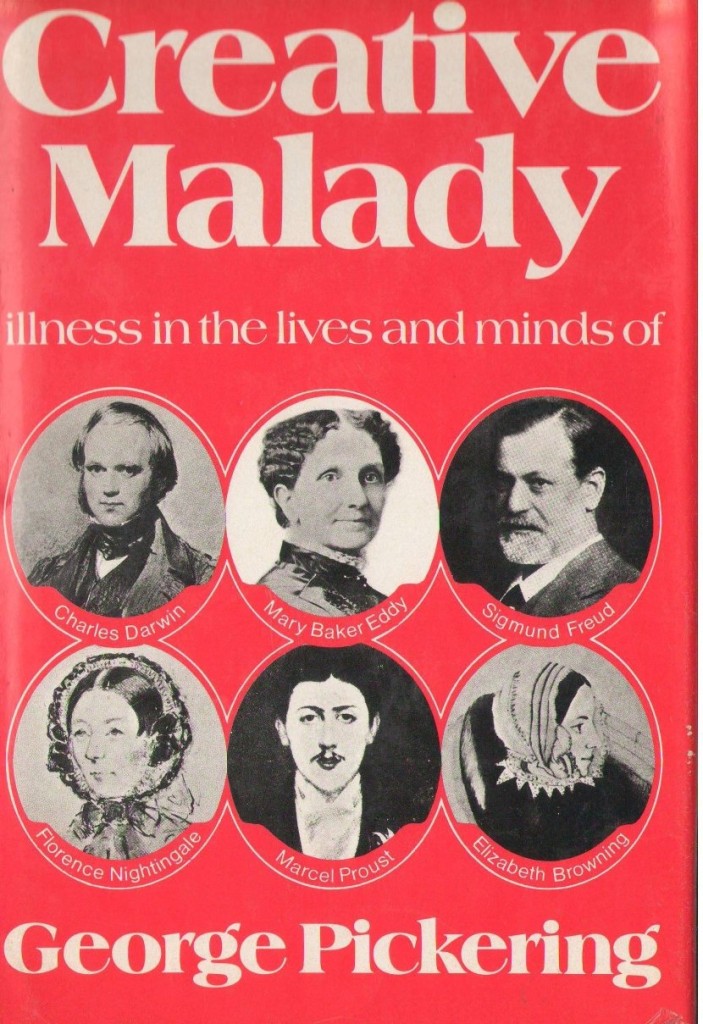

Pickering was certainly working with inadequate tools and resources – as Beachcombing suspects the author himself would have admitted. But he found inspiration in the lives of an unlikely series of individuals including Charles Darwin, Florence Nightingale, Mary Baker Eddy, Sigmund Freud and Marcel Proust!

All of these individuals, to one extent or another, suffered from an illness that Pickering believes was unconsciously created. And what would cause this kind of self sabotage? Well, GP argues that actually it was not sabotage but a strategic act. The illness was a way of protecting the individual from society and the claims of society– ‘a social weapon’ – demanding more care and attention from loved ones and keeping disruptive elements at arm’s length. The dreadful Florence Nightingale for example had ‘flair ups’ whenever her even more dreadful mother or sister came to visit.

Indeed, according to Pickering, Temps Perdu, Christian Science and the Oedipus theory were all creative acts brought about by these ‘charmed’ illnesses, while Darwin’s theory of evolution was also honed under the ventilating ostrich feather of a psychosomatic condition.

It strikes Beachcombing that these were not all happy contributions to nineteenth and twentieth century life, but anyway…

So was Pickering correct? Beachcombing is suspicious of doctors when they have a patient in front of them, never mind when they are reconstructing an illness from incomplete records. But if this book is only partially right it offers an interesting glimpse into illness and its interface with the mind from a paid-up member of the British medical establishment.

If it is wrong it is a fascinating look at that interface with expert analyses of six or seven illnesses that plagued the life of the good and great thrown in.

Beachcombing has become obsessed in the last six months by the idea of psychosomatic illnesses and placebo. Any other reads please let him know: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com