Prospero the Etruscan and Lying Historians February 13, 2011

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient, Modern , trackbackLiars and history go together like a horse and carriage. Beachcombing gave a chance reference to Herodotus as ‘Father of Lies’ in yesterday’s post. ‘Pseudo-‘ and ‘Mythic-History’, typically found in tribal societies, are porkies by modern standards. But most interestingly, at least for Beachcombing, are the scholars/antiquarians who betray the very rules that they claim themselves to follow. Consider, for example, Thomas Chatterton with his ‘Rowley’ poems or Iolo Morganwg forging Welsh triads or James Macpherson’s Ossian or, for that matter one of Beachcombing’s bêtes noirs, Donald McCormick cooking his Ripper or John Dee books: and we’ve not even left the shores of Britain…

Beachcombing, in any case, never gets tired of these types and so was overjoyed when a seventeenth-century noble from Volterra, Italy appeared in a tome he was reading last week. Welcome to centre stage, Curzio Inghirami!

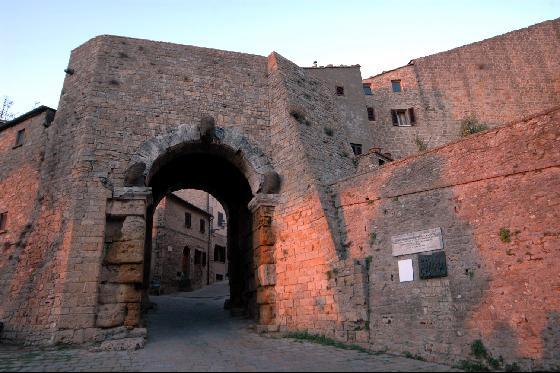

Curzio’s story is quickly told. Aged 19, out for a stroll with his sister and a man servant, CI is alleged (by CI) to have stumbled on a scarith in the earth of his family’s estate, a peculiar container made of pitch and fabric containing a paper slip. The paper slip was the first of more than two hundred messages from the Etruscan past that CI would dig up in the next fifteen years and all, it transpired, were the works of one Prospero, an acolyte priest, trapped in Volterra (whose Etruscan walls are pictured here) during the Roman siege of the city, his charms about to be overthrown…

Prospero wrote in Etruscan, naturally, indecipherable at that date and almost indecipherable today. But he also, doubtless for the benefit of future generations, wrote in Latin. His Latin was, however, strangely ‘Tuscan’ with numerous slips from classical standards. There were other inconsistencies too. The Etruscans tended to write from right to left, rather than from left to right as Prospero did. The Etruscans did not use paper. And, perhaps most strangely, one piece of ‘manuscript’ from the collection had a seventeenth-century Tuscan watermark!

Yet, the ‘antiquities’ had their defenders, the most passionate of whom was their forger – Beachcombing risks litigation here – Curzio himself.

Interestingly and almost alone among lying historians CI survived with his reputation publicly intact. After all, CI came from a noble family and so criticisms were sensibly muted. Though a score of scholars attacked the scarith nobody dared state in print that CI was responsible, blaming others for fooling the young man: mind you, some came painfully close with their insinuations.

The only book that Beach knows on the scarith is by Ingrid Rowland: The Scarith of Scornello – a worthwhile short-and-sweet read. The author concludes that all this was a fabulous practical joke by CI.

Beachcombing suspects that this is a twenty-first-century academic trying to put an interesting ‘modern’ twist on things and get away from the full horror of what CI got himself into.

It looks very much as if CI was caught in a lie and was unable to escape from the cage he had constructed about himself. As it was he was still claiming that the scarith were genuine in middle age, writing fervid diatribes – he died young-ish at forty one.

The best thing that could have happened would have been a minor public disgrace in Curzio’s late teens: a police report was written on the circumstances of the find. Then, the Archduchy being a forgiving place for wayward aristocrats, CI would have started again – an Etrurian second act – and become a lawyer or a salt magnate or a collector of saracen slave girls. As it was he spent much of his thirties forging medieval records in the Volterran archives, records that still bedevil historians to this day!

What is it like to dedicate your life to a lie? What happens when you find yourself abed in the late evening and look at the ceiling after ten or twenty or forty years of falsehood? Does it matter anymore? Do you stop thinking of it as a lie? Or is it like a mild toothache that never goes away? Beachcombing likes to think that he understands historical liars: he just doesn’t understand how they live with themselves, month after month, decade after decade, especially when the lie is at the very centre of their lives. Is this what the cross-dressing queen who is married to a suburban housewife feels when he is coaching the local litle league baseball team? There but for the grace of God…

Beachcombing would be interested in other historical ‘liars’: leaving their rubbish like so many potato crisp packets and coca-cola cans on the virgin fields of history. drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com