Kamikaze Exploration Irish Style April 11, 2011

Author: Beach Combing | in : Medieval , trackback

An entry from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles for 891 claims that in that year three Irish men set out from Ireland in a boat. An everyday event you might think – certainly Beachcombing was unimpressed.

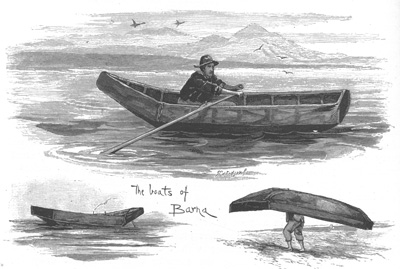

But what made their voyage special was that the three travelled without oars. In effect, they decided to give up their small vessel – likely a curragh – to the wind and sea, letting these elements – in which they saw the working of God’s will – decide their destination.

An isolated case of madness or eccentricity? Strange as it might seem the three belonged to a long line of Irish holy-men who, in the early Middle Ages, climbed into boats, raised the sail and travelled wherever ‘God’ would take them. The three started their journey at the end of the ninth century and with great good luck survived – they landed in Cornwall. But the tradition of Irish monks or ascetics in boats can be traced back to some of our earliest Irish records and the seventh century.

How on earth did the Irish settle on such a strange form of worship?

The answer has two parts – one native, the other foreign. The foreign stimulus is perhaps the most curious. The Irish were converted to Christianity in the fifth century. From almost the very beginning the Christian Irish had a reputation as great readers. They read, of course, the Bible, but also the Church Fathers – men like Augustine and Jerome, saints’ lives and other works of Christian piety.

In this impressive library some of the material that excited them most was the writing of the Desert Fathers. The Desert Fathers were those men and women, who, in the fourth and fifth centuries, had wandered off to live lives of devotion to God in the deserts of North Africa. Their writing described the day to day problems of hermits living in isolation.

What excited the Irish most about the Desert Fathers was the idea of a ‘desert’: a place where the holy-man could go to escape all interference from the outside world. There was, though, a big problem – Ireland had no deserts. The early Irish found two solutions. The first was to convert some of their bog-land into improvised deserts. To this day, there are many Irish place names containing the element ‘dísert’ marking the point where Irish hermits lived hundred of years ago.

The other, and a brilliant piece of lateral thinking, was to turn towards the greatest desert of all – the Atlantic Ocean, or an island in that ocean where the Irish holy-man could pray in peace. So strong was this concept in Irish literature that we read routinely that this saint or that went to ‘find a desert in the ocean.’

The Irish who hit on this idea of turning the desert into an ocean may have been influenced by a native Irish tradition that predated Christianity. In Irish law there was a punishment involving a boat and the sea. A criminal was tied to a boat, dragged out to sea – some texts say to the ninth wave – and then left to drift where the winds would take him. Bearing this native tradition in mind, it is interesting that the holy-men who left Ireland also gave themselves up to the wind. The possibility of the native tradition influencing the Christian one is strong.

An Irish legend about St Patrick may mark the point where the home-grown Irish tradition and the Christian idea of a desert collide. In the legend Macuil, a criminal, goes to St Patrick and confesses his evil deeds. St Patrick appalled by the gravity of the man’s sins condemns him to the following harsh penance.

‘I cannot judge, but God will judge… Go away to the sea without your weapons. And leave Ireland quickly, taking nothing with you save some poor little garment to cover your body with, and tasting nothing and eating nothing of the produce of this land… Then when you get to the sea, shackle your feet together with iron fetters and hurl the key into the sea. After put yourself into a boat made of skins, without rudder or oar, and go wherever the wind and sea take you and to whatever land God chooses.’

Patrick is providing penance for a man here that has committed a lifetime of sins. Most of the Irish holy-men who got into small coracles in the Middle Ages were not doing so for penance. Rather they were in search of a ‘desert’ where they could pray to God in peace – be it the ocean itself or one of its numerous islands. The most famous example is St Brendan of Clonfert who used to go off in his boat for forty days at a time – Christ went into the wilderness for forty days – and then came back to his brothers smelling of the perfume of paradise.

St Brendan’s Lives are extremely difficult sources. Often taken as evidence that the Irish had reached North America, they describe quite credible events in incredible ways. There is, for example, a description of the Gates of Hell that bears an uncanny resemblance to an Icelandic volcano, a crystal tower – an iceberg – and a whale who allows Brendan’s monks to eat on its back.

A more straightforward account is found in the Life of St Columba by Adomnán. There, we read that an Irish monk Cormac went three times in search of a desert in the ocean. The first of these missions was a failure because Cormac brought with him a man who had broken the monastic Rule. On the second he landed in the Orkneys, pagan at that time – and Adomnán implies that Cormac was lucky to escape with his life. However, on the third occasion we read rare details of just how terrifying one of these voyages – all in an Irish curragh of animal skins – must have been. ‘[Cormac’s] ship blown by the south wind, went with full sails in a straight course from land towards the region of the northern sky, for fourteen summer days and nights. This voyage passed far beyond the range of human exploration, and was one from which there appeared to be no return.’

Fourteen-day’s full wind could have taken Cormac close to Greenland. He allegedly only got back to Ireland thanks to the intervention of St Columba who prayed for his safe return. Others were not so lucky. They followed ‘the whale paths’ into the deepest Atlantic and were lost at sea or blown to the strangest places never to return. The custom was responsible, as we have already seen, for a landfall in Cornwall. Other Irishmen may have found their way to northern Spain. One ninth-century text describes Irish holy-men who had been washed up on Iceland. It was an extraordinary kamikaze form of exploration, but one that historians cannot afford to ignore.

Any other forms of kamikaze exploration? drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com