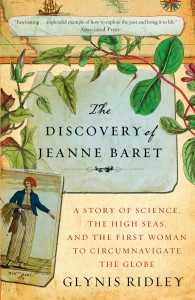

Review: The Discovery of Jeanne Baret January 21, 2012

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackbackIn 1766 Jeanne Baret, a young Burgundian, joined a round-the-world trip, a French mission to claim territory in the Pacific and Indian oceans. Her experiences, the subject of a recent book by Glynis Ridley, would have been remarkable in itself given her gender and the date. But as the French navy did not allow women on its vessels JB had to dress and act as a man, disguising herself in a cramped hulk where one sniff of oestrogen would have set three hundred sailors a-slavering.

Beachcombing has previously looked at some cases of women living their lives as men, including the remarkable James Barry. But Barry’s choice was a heroic and calculated defiance of the limits placed in his way by the patriarchs of Victorian Britain.

Jean B, on the other hand, was more object than a subject. She may have wished to see the world, she may have wished to botanise in the South Sea islands – she was an expert in plant lore. But she came, above all, as an assistant to her lover, Philibert Commerson: and if she came it was because he believed that it would be convenient for his botanical, sexual and house-keeping needs.

The fact that JB was an object rather than a subject makes it difficult to narrate her experience. It is not that there is a lack of sources. There were as many diaries written on the voyage as you would find in a modern British cabinet: self-conscious explorers are a little tiresome in that way. But JB wrote nothing. To recreate her story then you have to reach through the various accounts and in these accounts she is at best a bit actress. Think Rashomon, think The Ring and the Book and understand that there is a vacuum at the centre of the tale where there should have been a chest full of folios.

This is a particularly dangerous situation for an author, of course, because you need extraordinary discipline to rein in speculation and to avoid invention. Glynis Ridley largely succeeds employing the various snippets of information about JB, reading them with all the care of an eighth-century Biblical exegete.

When this works it works very, very well. Take the author’s chilling decoding of the allusions to a gang-rape on a far forsaken strand, the secret at the heart of the book. Beach took down his Massai lion-killing spear and indulged in some Kill Bill fantasies after reading that chapter.

The moments when the author fails are, instead, those that involve JB’s ‘keeper’, the botanist Commerson, an egotist and a rule-breaker, an object of odium for GR. We are going to give her a pass on this though as she was much provoked.

For Beach there is, in the end, something sordid in this book. The problem is not the writing which is intelligent and smooth, but rather the story itself. The three-year torture of any human being, woman or man, glimpsed or seen, on sea or land, is never going to be pleasant and JB would, frankly, have had a better time in a Japanese prisoner of war camp.

For those, of course, who are made of sterner stuff – Beachcombing’s favourite genre of film is the romantic comedy – then this should not be a problem. And even for shiny happy people there is, at least, an upbeat ending. JB is abandoned half way around the world and there she begins her transformation from object to subject. She marries a man who she seems to have loved and then makes her way back to France: becoming, in the process, the first woman to circumnavigate the globe. Then, later in her life, a friend in the French ministry wins her a generous pension. And, best of all, there is a post-mortem miracle. The publication of this book has encouraged a botanist to name a plant after JB.

In every way, Jeanne Baret was lucky in her biographer.

Beachcombing is always on the look out for unusual books: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

***

21, 1, 2012: Invisible writes: ‘Your post on Jeanne Baret reminded me of Hannah Snell, The Female Soldier, whose ‘autobiography’ I recently read at Gutenberg. Here’s some general background: How much of it is true and how much tarted up, I am not qualified to say. ‘ Thanks Invisible!!

14, 1, 2012: DC writes in with a new story (at least for Beach). ‘The story of Charlie Parkhurst is real. I grew up at a grade school adjacent to the graveyard where Charlie Parkhurst is buried. One year we went out and took tombstone rubbings. One rubbing that was shared in class was that of Charlie Parkhurst. By some accounts she was the first woman to vote.’ Thanks DC!

22.2.2012: Invisible references a FT article on Hannah Snell. Thanks Invisible!