Swallowing or Choking on (Operation) Mincemeat February 23, 2012

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackback***Dedicated to Glyndwr Michael***

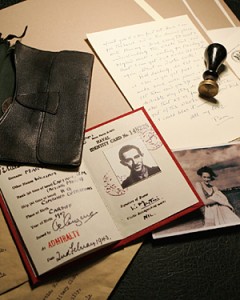

Operation Mincemeat is often celebrated as the single greatest act of trickery of the Second World War. In 1943 a Welsh suicide victim was dressed up in the uniform of a British royal marine, put on dry ice in a submarine, thrown into the sea off the coast of Spain with some ‘vital’ (ahem!) documents chained to his wrist; documents that were allowed, with the connivance of Franco’s regime, to fall into the hands of the Germans.

The Germans fell for the planted documents ‘hook, line and sinker’ (as one contemporary put it) and were led to believe that the coming Allied invasion of Sicily was a feint and that the Allies’ actual target was Sardinia and Greece. The story is well-known and has been the subject of several books and even a film (the Man Who Never Was, 1956, which includes, rather improbably, the IRA!) And much attention is justly paid in these accounts to the skill of the British team in putting everything from concert tickets to love letters into the pocket of their plant, constructing the ideal character to bait their false documents.

What Beachcombing was not conscious of until he read Denis Smyth’s recent Deathly Deception: the Real Story of Operation Mincemeat was how close the whole thing came to failure. As a lover of accident, insane coincidences and human stupidity Beachcombing notes five moments when the scheme almost blew up (once literally) in the face of the British.

1) The potentially explosive reverse came when a pompous official at Gibraltar – a particular British ‘type’ – refused to stop anti-submarine sweeps in just the area where the British submarine was going to surface with the body! After months of careful work in London it would have been a painful irony if this extraordinary plan had been blown out of the water by the British themselves.

2) The Spanish son and father doctor team who examined the body and looked at the documents – nepotism in Southern Spain, who would have guessed it? – somehow managed to misread the various pieces of information that had been stuffed into the pocket of ‘Major William Martin’. The fact was that the British had planned the rate of decay of body and the date of leaving London (hinted at in various documents on the body) to perfection: what they hadn’t banked on was the Spanish officials deciding that there was a discrepancy between the rate of decay and the dates that they had muddled by misreading the corpse documents!

Beachcombing is reminded here of various other British attempts to get one over on the Germans and the Japanese in the war, where tricks became just too sophisticated for a practical, matter-of-fact opposition. In the end, British intelligence decided that only the Machiavellian Italians could handle their rather precious and high-pitched sophistication: and, of course, the Italians didn’t matter…

3) Another problem with the autopsy was the photograph. As the British intelligence crew had not been able to photograph the victim for his identity card – he was very clearly dead – they had found a doppelganger. The Spanish doctors understood almost immediately that the photograph and the man looked different. Most worryingly the photograph had more hair around the temples. Surely the easiest thing would have been to have not provided a photograph and to have allowed the Spanish to assume that the identity card had gone missing from an open pocket? As it was the son and father team managed to explain away, to their own satisfaction, these inconsistencies, but once more the British were almost caught out by being – another British vice – too clever by half.

4) Here is Beachcombing’s personal favourite. When the representative of HM’s government, one Haselden, went to pick up the body a Spanish official, in an eighteenth-century act of chivalry, offered the precious briefcase to the British vice-consul with a why-don’t-you-just-take-it shrug. This was before the Spanish had been able to photograph the briefcase’s contents! The British vice-consul’s blood must have run cold for he was one of the few individuals in the know. He managed to bluster away that he would get in trouble if he took the case without it going through the proper channels. If Haselden had not been so quick thinking on his feet or if he had not been in the know then Operation Mincemeat would have ended there…

5) The Germans knew of the secret documents but they had to navigate their way through the not always friendly departments of the Spanish government. Franco’s officials ranged from men who had fought on the eastern front in the Blue Brigade, (ardent Nazis) to quietly pro-British officers. The Germans put up a fight to get the briefcase. But a little more Spanish inertia or slightly less enthusiasm on the part of the Germans would easily have seen the briefcase returned to the British unphotographed. Or, at least, the time sensitive material would not have been shared with the Germans but would have remained on the desk of some mid-ranking Naval Officer in Andalusia.

In other words, the British operation that, in the end, took in the entire German command (including that professional liar Goebbels!) was a close run thing. A British plane in the wrong place, another vice-consul, another autopsy team and Mincemeat would be a footnote, and probably a much mocked footnote in the history of the last war. But then who dares, sometimes, wins. Other close run things from intelligence operations: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com?

***

1 March 2011: Chris F. writes in with a US intelligence wheeze: Not quite as dramatic as the body shipped around on ice, but another well-known example: In the runup to the Battle of Midway, which many will agree was the most decisive battle in the Pacific War, a codebreaker’s clever idea may have made all the difference. Saying (falsely) that U.S. forces on Midway had a problem with their water supply, he watched for a spike in the use of the word water and was soon rewarded with unwitting confirmation that Midway was indeed the Japanese objective. A couple of days more and it probably would have been too late. The following is from an internet source I remember only as ‘Ultra’, sorry….: ‘Admiral Nimitz had one priceless asset: cryptanalysts had broken the JN 25 code. Since the early spring of 1942, the US had been decoding messages stating that there would soon be an operation at objective “AF.” Commander Joseph J Rochefort and his team at Station Hypo were able to confirm Midway as the target of the impending Japanese strike by having the base at Midway send a false message stating that its water distillation plant had been damaged and that the base needed fresh water. The Japanese saw this and soon started to send messages stating that ‘AF was short on water’. Hypo was also able to determine the date of the attack as either 4 or 5 June, and to provide Nimitz with a complete IJN order of battle. Japan’s efforts to introduce a new codebook had been delayed, giving HYPO several crucial days; while it was blacked out shortly before the attack began, the important breaks had already been made. As a result, the Americans entered the battle with a very good picture of where, when, and in what strength the Japanese would appear. Nimitz was aware, for example, that the vast Japanese numerical superiority had been divided into no less than four task forces. This dispersal resulted in few fast ships being available to escort the Carrier Striking Force, limiting the anti-aircraft guns protecting the carriers. Nimitz thus calculated that his three carrier decks, plus Midway Island, to Yamamoto’s four, gave the U.S. rough parity, especially since American carrier air groups were larger than Japanese ones. The Japanese, by contrast, remained almost totally unaware of their opponent’s true strength and dispositions even after the battle began.’ Thanks Chris!