Pixy Music on Dartmoor July 15, 2012

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackback

This is a fascinating story from Dartmoor in 1921. A director of orchestra has decided to walk out from a musical boot camp and try his hand at composing in the middle of the heather. It is there that he has a very strange experience: this one is dedicated to all lovers of auditory illusions.

That is what the scene is on the stage. But out on the open moor in sunlight two months before rehearsals began I had to imagine what it would be like; I could not know. The only way of fitting the music and the sense was to work by time and calculation. I had the text, the Family Bible and a stopwatch for tools, and for a guide the memory of Stanford’s harsh voice giving the advice that every composer for the theatre must lay to heart: ‘Pace it, me boy, pace it.’ Pace it I did, to and fro among the heather, conducting to the empty air. That section seemed all trim. Now time it. I got down again flat on my belly, set the stop-watch: go. Solo viola lead at the cue to ‘Will!’ Will’ – thirty one seconds – put repeat bars in for safety; violas again at ‘Let me pass’ – thirteen seconds; Portia’s harp entry – better have a pause at the second bar – four seconds; the ‘St Valentine’s Day’ for Orphelia – seven seconds. And just then I heard my own name called. ‘Tommy! Tommy!’ And once more nearer ‘Tom-my!’ There was no one in sight. I picked up the field glasses to make sure. The moor was as empty as the sky. Picknickers sometimes wanders along the Teign, behaving oddly, but this eyrie was out of their ken, hard to find; and even if the wind had been more than a fitful summer breeze the river was to leeward. And I had not dozed off. I was most certainly and completely awake, with a stopwatch ticking in my hand. Searching for intruders seemed futile, yet I did search irritably. I knew I should find nothing. That voice had sounded quite near. Within twenty yards. It was not the voice of anyone in camp. And no-one in camp called me Tommy. They knew better. Thomas, yes, or Tom; but no diminutives. That was agreed on. And no one I could bring to mind had a voice of this particular quality. It was small, quite clear, faintly mocking, pitched high. Yet it was not a woman’s voice. It might even have been a man’s if he slipped easily into falsetto. Had I been honoured by a visit from a Pixie?

It is a question and intrigued our hero returns to exactly the same spot the next day: the first sentence reminds Beach that there is a study to be made of weather conditions during fairy (and UFO?) sightings.

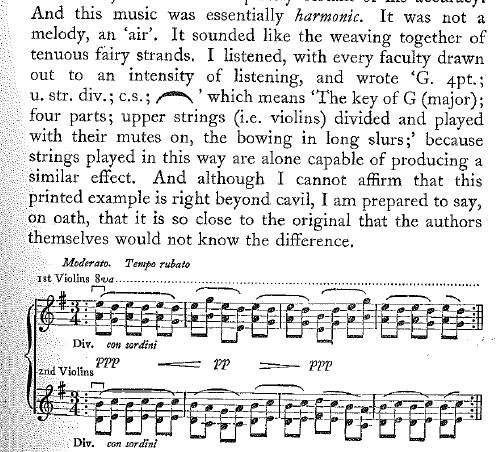

I went back to the same place next day. The weather was more steamingly hot than ever. Dartmoor was asleep; so were the bees, the hawks, the wind, and the tors filmy against the blue. Everything asleep but me. I kept most brilliantly and tenaciously awake, listening, prone by the rowan bush on top of the family bible and trying to work at the second part of the Masque. An hour went by; an hour and a half. The shadows lifted as the sun moved. No other change. And then I heard the last thing I could have expected to hear – music in the air as faint as breath. It died away; came back louder, hung over me swaying like a censer [inspired image!] that dips and swings, and is withdrawn. In all it lasted twenty minutes, which was a period of time quite long enough for me to settle that no human agency within my knowledge could bring music of that kind into that place; and more mature reflection still leads me to believe that this conclusion was right. Portable wireless sets were unknown in 1921; heather-covered moor will not carry sound far and the day was a roaster; my field glasses again assured me that no picknicker was in sight, still less a gramophone, and what I heard could not possibly have been music of the mind extraverted into music for the ear. Nor was it music that resembled in the least the music that I had just written or even music that I wanted to write. The key, style and scoring of the two had nothing in common. It would be a fine and swaggering claim to assert that I made exact notes of what I heard, but it would be unscholarly and untrue. Taking down an unfamiliar tune at one hearing is not easy, and I have yet to meet the man who can take down a four-part harmony, played at speed, in such a way that he is completely certain of his accuracy. And this music was essentially harmonic. It was not a melody, an ‘air’. It sounded like the weaving together of various tenuous fairy strands. [the rest of the text and the music bars can be found in the image above]

The author then goes through looking for references to fairy music: Joan of Arc, visits to the British Museum, Thomas the Rhymer and Robert Kirk. But nothing on the nature of the music… This is certainly – by far! – the best passage that Beachcombing knows.

‘Chance gave me what research did not. I read ‘Some Irish Fairies’ in John Masefield’s A Tarpaulin Muster. This was the first confirmation I had met with that supernatural music could be harmonic, and not merely a tune; and one day I asked Mr Masefield if he himself had ever heard pixie music. No; but he had talked to those who had, in Ireland. And what, please, did they say it sounded like? ‘A waving in the air’. That was it, exactly! All the proof I needed and better proof than I could have hoped to get.

Any other examples of fairy music described? drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

***

16 July 2012: DY writes in: ‘Well, something I don’t usually tell people – happened long ago. I was bought up near the Teign on the edge of Dartmoor (in the National Park, but not on the high moor). So lying in bed in bed when I was about 8/9, windows open, summer night – it was gloaming coming on night I always remember ‘bells’ – well at least that’s how I think of them. A lovely music, like glass bells – very very beautiful – and I remember thinking ‘who is playing’. There was no TV on downstairs, no radio outside (it was a big house too) and my bedroom window faced out over a lawn to an uninhabited valley leading to the Teign Gorge – nobody living there at all. Nearest neighboring house on other sides would have been about 300 meters or so. Now I’m of above average intelligence (so say we all!), well read etc. but, I heard fairy music alright. Auditory hallucination…? Well that claim is based as much on belief as fairies, only without the experience of being there. I won’t belabor this, it’s stuck with me all my life (this happened about ’66/67) and it’s always been a thing of beauty for me’ For more bells on Dartmoor see Bray’s A Peep below. Note that DY suggested (in a subsequent email) that the whole experience lasted about 5-10 minutes (‘Never thought of it. I’d be a bit suspicious of pinning it down after this length of time.) Next up is Wade: In an odd coincidence, I am researching Alasdair Alpin MacGregor and have open The Peat-Fire Flame (1937), when I see today’s Strange History post. MacGregor’s book contains a chapter on Scottish faery music, beginning at page 29. Then Invisible: As a musician, the idea of fairy music is intriguing. I am a little sceptical about its objective reality, having fallen prey to auditory hallucinations myself and knowing too much about tinnitus and similar ailments as well as aural pareidolia. However, I will pipe up with some unearthly musical anecdotes: Fairy Tales, Now First Collected: To which are Prefixed Two Dissertations 1. on Pygmies 2. on Fairies by Joseph Ritson, Joseph Frank TALE XXVI. FAIRY-MUSIC. An English gentleman, the particular friend of our author, to whom he told the story, was about passing over Duglas-bridge before it was broken.down ; but, the tide being high, he was obliged to take the river; having an excellent horse under him, and one accustomed to swim. As he was in the middle of it, he heard, or imagined he heard, the finest symphony, he would not say in the world, for nothing human ever came up to it. The horse was no less sensible of the harmony than himself, and kept in an immoveable posture all the time it lasted; which, he said, could not be less than three quarters of an hour, according to the most exact calculation he could make, when he arrived at the end of his little journey, and found how long he had been coming. He, who before laughed at all the stories told of fairies, now became a convert, and believed as much as ever a Manks-man of them all*.*Waldron, as before, p. 72. A little beyond a hole In the earth, just at the foot of a mountain, about a league and a half from Barool, which they call The Devils den, “is a small lake, in the midst of which is a large stone, on which, formerly, stood a cross: round this lake the fairies are said to celebrate the obsequies of any good person; and I have heard many people, and those of a considerable share of understanding too, protest, that, in passing that way, they have been saluted with the sound of such musick, as could proceed from no earthly instruments.” p. 137. There is a rather strange book, more in the spiritualist line, called NAD Vol. 2: A psychic study of the “music of the spheres” by D. Scott Rogo, foreword by Raymond Bayless. The cases are roughly arranged by the condition of the witness at the time of the hearing: just waking, having an out-of-body experience, at a deathbed, etc. Although some witnesses describe the music as “heavenly” or “angelic” many of the examples seem to have traits similar to descriptions of fairy music, being described as sounding like water or wind or bells. For example: Case 138 John Huntley related the sensation of being out of his body: “I became conscious of what for want of a better term I must call music; gentle and sweet it was as the tinkling of snapping water in a rocky pool and it seemed to be all about me.” Case 154, at a deathbed overlooking an area of green hills, surrounded by family, was heard “a strain of melody more divinely sweet than any earthly music they had ever heard, rose near at hand. It was the melancholy wail of a woman’s voice, in accents betokening a depth of woe not to be described in words. [banshee?] It lasted several minutes, then appeared to melt away like the ripple of the wave…As the last note became inaudible, the child’s spirit passed away.” Case No. 159, at another deathbed “we both compared them to the striking of a bell which was deficient in melody, but in the reverberation of which there is music…it almost took my breath away…..[the author tells of his sleep being disturbed by the bell music, which would suggest tinnitus or something similar–except his wife could hear it too. Strangely, there are medical reports of noises issuing from ears, which are audible to others. Later in the tale] “The sound of bells had gone and tones of flutes took their place…the tones of the flute had now vanished again, and we could only compare it to the singing of a choir with musical accompaniment.” Case 144 tells of an 8-year-old boy believed to be on his deathbed who said to his sister: Oh, what a beautiful sight! See those little angels.” “What are they doing?” asked the sister. “Oh, they have hold of hands, and wreaths on their heads, and they are dancing in a circle around me. Oh, how happy they look and they are whispering to each other…” “Do they say anything to you?” “Yes, but I can’t tell you as they tell me, for they sing it beautifully. We can’t sing so.” Other cases describe the music as “crooning or humming very sweetly sung, but the words not distinguishable”, and “a swarm of bees around me…I could hear the singing of the hymn ‘O Paradiso’ until it died away in the distance.”. One gentleman (in the “pseudo” cases section) heard a female voice singing a song which he transcribed and recorded. He claims it has the ability to lift depression. The book also has a chapter on mystic music heard in connection with the Welsh Revival and refers to some cases in Phantasms of the Living, by Gurney, Myers, Podmore. Rogo quotes Dr. Wilder Penfield, director of the Montreal Neurological Institute. In 1955 Penfield reported on his experiments placing electrodes on the temporal lobe cortex: “A young woman heard music when a certain point in the superior surfaces of the temporal cortex was stimulated…She was quite sure each time that someone had turned on a gramophone in the operating room.” Perhaps one of your neuroscientist readers can bring us up to date on what has been discovered about the temporal lobe/mystical experiences/music from modern brain mapping. Case No. 142 in NAD Vol. 2 is about music heard at the deathbed of Wolfgang Goethe. It is a long passage and so I’m linking to this page, which quotes bits from it and also has other examples of mysterious music: I have mentioned it before, but there is a fictional story by Saki, “The Music on the Hill” that uses fairy/panic music to chilling effect: . This comes meanwhile from Bray’s a Peep at the Pixies: On the borders of Dartmoor, in days of yore, there lived a rich old farmer, in one of the fields near whose house, stood a very curious object, a large moor-stone rock, shaped by nature so much like an ancient Gothic church with a tower, that it was known among the country people for miles round by the name of The Pixies’ Church’. It was also encompassed by a Pixy ring; and many old persons declared that ever since they could remember, if you placed your ear close to the rock on a Sunday, you could hear a small tinkling sound, resembling the church bells at Tavistock, and usually at the very time they were ringing to warn the good people of that town for the morning service. It was said, likewise, that the same sound could be heard when the bells of Tavistock chimed, as they always did at four, and eight, and twelve o’clock. One old woman protested that so long ago as when her great grand-father, who was fond of music, was a little boy, he was frequently seen to place his ear against the rock to listen, as he thought, to the Pixies’ ringing; and although he had never been at Tavistock, he thus learned the tune of the 100th Psalm which the chimes there used to play daily. He declared that he heard the Pixy music best when he put his head in a hole in the portion of the rock which was called the belfry tower. When he grew up to be a man he learned to play on the bass viol with which he led the choir of a neighbouring village; and it was always noticed that there was no tune he played with so much spirit as the 100th Psalm, which he had so often heard at the belfry rock. ‘And, as sure as you are alive’, said the ancient dame, who repeated this story round many a Christmas fire, ‘the Pixies love bell-ringing, and go to church o’ Sundays’. Thanks Invisible, DY and Wade!