Casualties and Memory September 3, 2012

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackbackThis post was written as a response to a memory that has been whirling around and around in the last few days. The only time Beach ever saw his grandmother – a fine old English matron – weep was when she talked about the First World War. She had, in fact, no direct experience of WW1; she was born immediately after it. But her family had lost several male members and the ripples of horror kept spreading outwards. Those ripples will not reach Beach’s own children: to them WW1 will matter as much as the Napoleonic wars do to us. But those ripples were strong enough to shake the harbour buoys in Beach’s own childhood. And this is a national not a private obsession. The British still remember their war dead in terms of the First World War. They wear poppies from the Somme to commemorate the fallen. British politicians meet at the First World War cenotaph in London for their minute of silence. And British schoolchildren are force-fed Great War poetry like vitamin tablets.

Yet Britain is alone among the major combatants in its interest on the First World War. All the other major combatants concentrate their war angst solely or almost solely on the Second World War, whereas Britain – and its old dominions: Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa – mix and match: with the WW1 playing the pity-of-war to WW2’s just war. A silly example. Every fall semester Beach teaches a class of American students an introductory history course. As one of his exercises, he asks them to write down six dates that represent the history of their country. No student ever misses out 7 December 1941. But Beach has never had a student mention the Great War: though typically the Depression does feature.

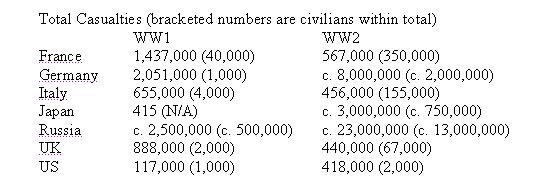

Why does Britain alone remember WW1 in this way? The answer has to be casualties. At the head of this post is a table of WW1 and WW2 casualties with the seven major powers that fought in both wars. Of those powers, only three, Britain, Italy and France lost more citizens in WW1 than in WW2. The US, Germany, Japan and Russia all lost many more citizens in WW2 than in WW1.

Imagine that you are Japanese and that you are living in 1960 and you look back at the landscape of the past. WW2 is a mountain close by that dominates the horizon and the little mole hill of WW1 is nowhere in sight, obscured behind that mountain. A Russian looking back at the wars from 1960 can hardly talk of a mole hill for WW1: two million Russians died. But as 20 million plus died in WW2 the earlier war is again obscured. Ditto Germany. Ditto the United States. Why worry about shrapnel at Ypres when you have Stalingrad and Iwo Jima?

France and Italy have different experiences. It is true that both countries had fewer casualties in the later war. But there are complicating factors. Italy was invaded twice (simultaneously) and enjoyed a fully-blown civil war in the north. There were additional traumas then that more than made up then for the bonus of fewer deaths and that still divide the country today. France’s lower casualties mean that it remembers the First World War in a way that is comparable in some ways to Britain: Verdun is a name that will remain resonant in French for the next century. But if France had a third of the casualties in WW2 it also had an invasion, which its post war political class found shameful and the mixed good of national resistance through five years of covet fighting.

In short when a French or Italian citizen looked from 1960 back over the landscape of the past, the ugly peaks of the First World War reared behind WW2. But there were a lot of dark clouds and lightning, flashing around the nearer peaks, obscuring the view. A Briton, on the other hand, looking back in 1960 saw a hill (WW2) and the Great War mountain towering behind it in brilliant blue skies. Even Singapore and Dunkirk, Coventry and the Arctic Convoys could not wipe out the memories of non-commissioned officers with whistles and revolvers and the rat-a-tat-tat of German machine guns.… The paradox hiding away here is, of course, that Britain came far closer to defeat in the Second World War, despite its lower casualties. May God spare us a third.

Other thoughts on casualties and memories: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

***

4 Sept 2012: Rabbit Hole writes: ‘Beach, a few very small gripes here but for the sake of exactness. Of course, some of these borders were not the same in 1914 and 1939. This is true of France. But it is particularly true of Germany and Russia. Sure, it doesn’t make a huge difference but it places the number in a different context.’ KMH, instead, I can sympathize with Britain’s memory of WWI because it was peculiar in how far weaponry (the machine gun particularly) had advanced beyond effective tactics, at least in the beginning. One major participant of WWII you didn’t mention was China, estimated to have had 15,000,000 casualties…. There can only be reasonable estimates in both wars. Another factor was the large number of casualties in Eastern Europe, particularly Poland, in WW2. Japan changed from an honorable nation in WW1 to its opposite in WW2 under the influence of the Nazis. In terms of brutality and bestiality, Japan didn’t always come in second to the Nazis. The stain on Japan’s honor continues to this day in Eastern Asia.’ Thanks Rabbit Hole and thanks KMH!

5 Sept 2012: KB writes: ‘It seems that there was a time after WWI when everyone was saying “Never again! We fought this Great War to end all war.” But WWII came much too soon afterward with a great disillusionment: WWI had not ended all war. Perhaps the remembrance of WWI is, in some part, a yearning for the days of relative innocence and illusion, when people believed that the sacrifices made were for the cause of ending war entirely. A thought on this I’d like to share: before we humans were civilized, we offered a human now and then in sacrifice, essentially to “keep the world safe” and honor ideals and traditions by propitiating whatever gods or monsters were imagined. Now that we are civilized, we have a war now and then “to keep the world safe” I suppose, and honor ideas and change traditions. The human sacrifices are in the millions. Not that we should go back to occasional human sacrifices. But will we ever be able to end human sacrifice altogether? Will we ever come to a time when no man tries to be god and we all stop acting like monsters?’ Thanks KB!

7 Sept 2012: Invisible writes: I had a beautiful radical theory of why Britain still mourns the First World War, but statistics did not bear me out. Pooh…. But I’ll put it out here anyway… The Spanish flu pandemic hit in January 1918. Soldiers were unusually hard-hit by the pandemic, which seemed to target ages 20-40. Is it possible that, outside of Britain, many of the soldiers who would have perpetuated the memory of the First World War died, along with others at the start of their adult lives? Left behind were the infants and the aged–the first would have no memory of the War; the second would have no first-hand knowledge of it. I’m not all that good with numbers, so bear with me here: The population of Great Britain in 1918 was roughly 61,000,000 souls; About 250,000 died: roughly 0.4%. According to US Census figures calculated for 1918, there were about 103,200,000 people in the US; 500,000-675,000,between 0.48-.067 died of the influenza. How many of these casualties were soldiers? There was a slightly higher ratio of deaths to population in the US than in Britain. Not that Britain was “spared”, but comparatively lighter casualty rates might have allowed British soldiers to return and be the focus of national mourning. Also, in the US, returning soldiers were diffused–back to the farm in Kansas or the mine in Colorado or Pennsylvania–over a much larger geographical area. No Cenotaph; no poppy sellers in London. My Grandfather was a bandsman in the First World War, which kept him out of harm’s way. But he never spoke of the War. I was not conscious of any other veterans of that War except the men in his American Legion band who paraded on holidays and played while a Memorial Day wreath was thrown into the river. I spent a lot of time with people of that generation and I never heard (or overheard) anything about the War. Nor about the influenza, although now, as an adult, I have heard tales of how garlic (eaten and lined up on the windowsill) kept one side of the family from catching the disease as well as stories of children playing on piles of coffins. But for a long time it was as if that entire decade was erased. In a side-note to the influenza pandemic, Andrew Price-Smith, who wrote Contagion and Chaos, controversially suggests that casualties were higher in Germany/Austria than in Britain and France, which helped the Allies to victory. Thanks Invisible!