Generals, Entrepreneurs or Politicians? September 6, 2012

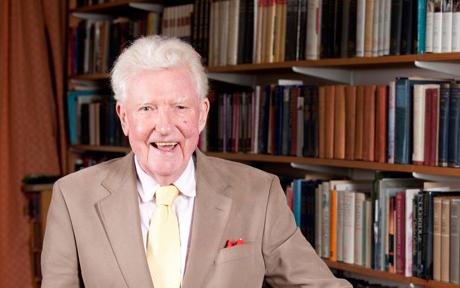

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary, Modern , trackbackPaul Johnson is a journalist and historian who Beachcombing considers the single most irritating Englishman alive. However, and this is perhaps part of why Beachcombing finds PJ so irritating, he can be extraordinarily perceptive: though anyone with their finger hovering over an amazon buy button should know that this is far from an inevitable outcome. In any case, Beach recently stumbled on a comment of PJ’s that he is going to give some space here because it is has given him several days of troubled thought.

PJ stated that Britain was able to benefit, 1850 to 1950, from a political class of a far higher calibre than its main rivals, the United States and Germany. Why? Essentially, PF argues that if you were a talented male born in America in 1850 then you aspired to be an entrepreneur. If you were born in Germany in 1850 (proto-Germany let’s say) you aspired to be an artist/engineer or (in Prussia) a general. If you were born in Britain the best that life could offer was to represent your borough and become a Member of Parliament. In Britain, people scrambled to cover up their entrepreneurial pasts by marrying into the aristocracy at the earliest convenience. In the United States stupid younger sons went to Congress and had arguments about harbours in Guam. And in proto-Germany and Germany politics was seen as a disgusting abstraction: Nazis made much of this in 1933 and 1934.

What results flowed from these differences? According to Johnson Britain’s political classes ably steered it through some very stormy waters as the Empire reached its zenith and then sank beneath the horizon. Germany’s political class failed to prevent talented generals and nationalist leaders dragging their country into two wars: both that were reckless and, as it turned out, catastrophic gambles. America’s political class was, meanwhile, hopelessly parochial and refused to get involved in international affairs until Japanese carriers hoved into view in the December of 1941. Britain, according to the rules of power, should really not have ruled the waves from 1900-1939, but America’s isolationism meant that it was able to.

Does all this add up? Beach is not much of a fan of politicians and, for what it is worth, if world history was reduced to a computer strategy game he would place his ‘culture points’ in entrepreneurship rather than politics: better younger and useless sons in Congress than dolts running your banks and factories. And as to American isolationism…, well, world domination is overrated. Ask a marine in Afghanistan. Other views: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

But PJ does catch perhaps the essence of Victorian and Edwardian Britain with his analysis. There is no question that Britain made some serious political mistakes in the nineteenth and twentieth century. Why, for example, was Britain’s political class so blind to Ireland: even when Gladstone harangued them with common sense? Why did all British parties effectively appease Nazi Germany and Italy? And why, oh why, oh why did Britain sign the Treaty of Rome?

But the overall picture is impressive. Britain’s political class retained a degree of unity that was unusual. It had a consensus-seeking right based, in part, on an aristocratic class with a strong sense of duty ‘to the lower orders’. It had a left that was, generally-speaking, independent, practical (inimical to Marxist abstractions), patriotic and often monarchical. And, for the second half of this period, it had a centre party that bridged the divide between the two ‘enemy’ political movements. This was mirrored in the country as a whole. The middle classes were instinctively conservative, but they had a radical and socialist quarter. And likewise between a fifth and a quarter of the left-leaning British working classes were Conservative voters. There were blocks then but they shaded into each other rather than becoming discreet entities.

As a result there was the possibility of what might be called the snap reflex. There was much gladiatorial fighting in parliament, but few deaths. And the moment that real crisis arrived the fighters dropped their swords and created a shield wall against any external enemies. Beach can’t help thinking of those infinitely grumpy Italian city states in the Renaissance where citizens would spend their time and energy in constant low grade civil war, but who would unite in a moment when the bell rang to announce the arrival of the army of Milan or the Emperor on the edge of their contado.

Britain’s war cabinets in both World Wars were models of unity and common purpose. Even in pre and post-war crises where different parties took different sides or had different loyalties – the General Strike of 1926 for instance – there was usually the ability to meet and to talk: perhaps in no small part, though Beach finds this an uncomfortable fact, because the MPs of all parliaments had been to the same schools and, typically, the same two universities.

***

7 September 2012: Southern Man writes: ‘I would be interested to know what clever young men and women do today in the UK. My bet is think tanks or to adapt that horrible phrase that characterises the last fifteen years: try and convince people to click on things. KB writes, meanwhile: There is nothing in genetics that shows second sons (or third or fourth) are less intelligent or less capable in any way than first ones. So this particular premise seems quite lame as an explanation for the variations of political strengths or weaknesses in any country, much less between countries. However, it does point to traditional modes of thought in reference to primogeniture: that the first son is the best son all round, and second sons are second best: unless of course first son dies, leaves, or rebels greatly against paternal control in which cases, second son will do quite nicely. A strange idea really, that second sons are stupid or useless.’ Beach should note that this may have been his rhetorical flourish rather than PJs, it certainly represents a widespread idea though. Thanks KB and Southern Man!