Italy’s Weird Languages February 4, 2013

Author: Beach Combing | in : Actualite, Contemporary, Medieval, Modern , trackbackItaly is chaotic not just in day-to-day but also in geographical terms. The Apennines that come down from the Alps dominate most of the country and separate out the peninsula into two hundred semi-independent shangrilas. The result is that Italy has always been doomed to social, cultural and linguistic division. Italian itself, the ‘dialect’ of Florence was only spoken by about 10% of the population at the time of unity in 1861: many Italians today still prefer their dialect over the national tongue. Then there are also substantial German-speaking, Slovene-speaking and French-speaking minorities in northern Italy: the result of an extraordinarily badly judged frontier. But of all the linguistic confusion that Italy’s geography has allowed the most interesting cases are the survival of five tiny fossilised language groups within Italy.

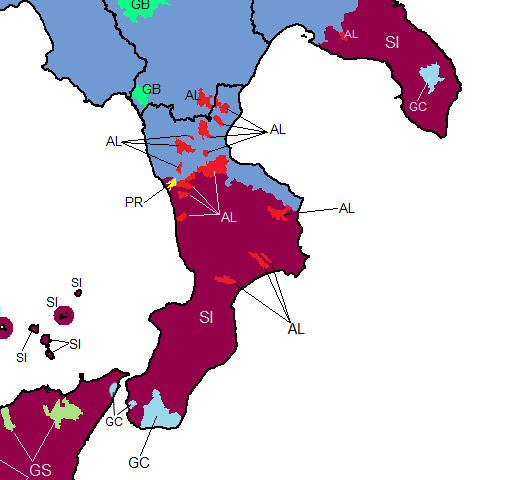

1) Greek: The most exotic of all these tiny families are the Greek speakers of Calabria and Apulia. By some estimates there are today fewer than five thousand southern Italian speaking Greek or Griko as it is typically called, the vast majority over forty years of age. (This is a language that is headed for the abyss.) Where did Griko – labelled GK on the map below – come from? Here linguists have argued for years. One school claims that Greek in the south dates back to Byzantine domination in the Middle Ages when much of southern Italy spoke that language. However, there are a second group of academics who claim that Griko predates Justinian’s reconquest and the East Romans. They claim that Griko is the last trace of Magna Grecia, the Greek colonies founded in southern Italy in the first thousand years B.C. Needless to say the second may be the prettier of the two but it is also a minority opinion.

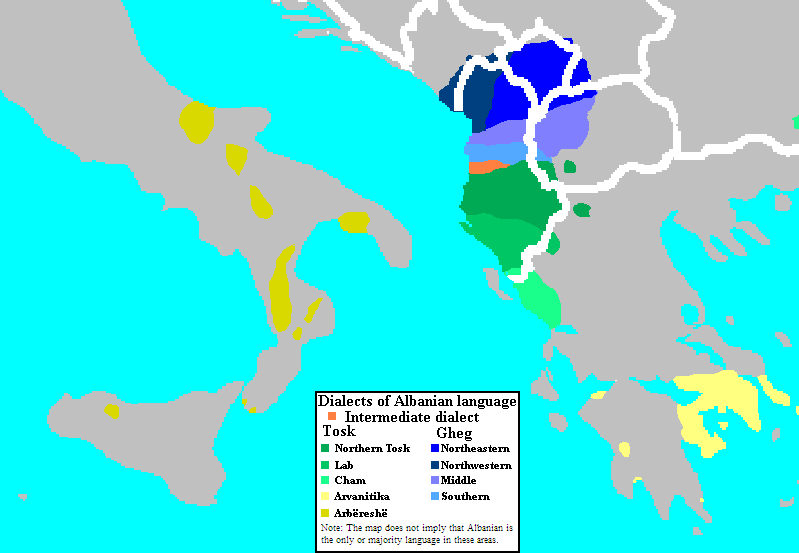

2) Albanian: Italy has been inundated with Albanians in the last thirty years, in fact, Albanians constitute one of the least popular immigrant groups in the country today. But scattered through the south of Italy there are Albanian or Arbërëshe speakers who speak a tongue that is close to modern Albanian, but who have been established in southern Italy for centuries: Arbërëshe is, in fact, an archaic version of the Albanian spoken in southern Albania. They began to come to the southern peninsula as agents of Byzantine rule in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Then, as the Ottomans overran Albania in the fourteenth century other waves of immigrants headed Italywards for the next three hundred years or so. The results is that today perhaps as many as 100,000 Italians have some Arbërëshe. Naturally, there have been rather peculiar meetings between the new and the old Albanians in ‘foreign’ Italy.

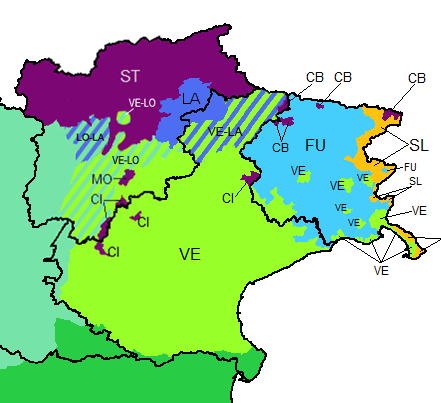

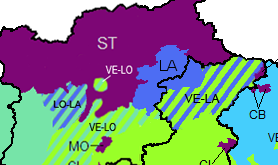

3) Cimbrian: There are large German-speaking minorities in the Sud Tyrol, within Italian territory. However, there are also Germanic-speaking islands deep in the Veneto in north-eastern Italy (see CI on the map below). These ‘islands’ speak not German, as we understand it, but Cimbro. The origins of Cimbro are controversial. Some scholars claim that Cimbro is the last trace of Lombard from the barbarian invasions of the sixth century. However, most believe that Cimbro derives from Bavarian populations that came to live in Italy in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Cimbro should be intelligible to a German-speaker, and written out it bears some resemblance to modern Hoch Deutsch, but when spoken a German-speaker will find it impenetrable. Naturally, Cimbrian is another dying language: perhaps two thousand speak the tongue today.

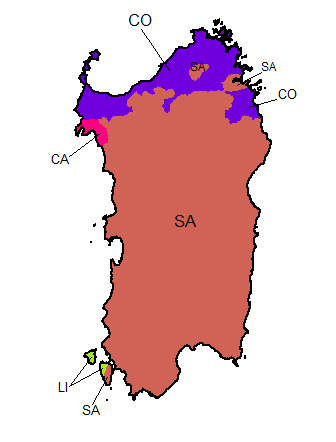

4) Algherese: Catalan is, of course, a minority language in Spain. But this minority language crossed, in the Middle Ages, the Mediterranean to north-western Sardinia where it was established in the fourteenth-century in the town of Alghero (see CA on the map) as a minority language surrounded by a minority language (Sard the language of the island). Today about five thousand Algherans speak Algherese that is essentially a medieval version of Catalan, transplanted westwards. Again this language is an important part of local identity and again its survival is anything but guaranteed.

5) Ladino: About fifty thousand northern Italians speak Ladino, essentially the language called in English Romansh, the native Latin tongue of Switzerland. To hear Ladino is to be confused. At first, the rhythm of the speech suggests that someone is speaking German or at least a German dialect, but the words are, in large part, Latin in origin. Ladino has perhaps a more self-confident tradition than the other languages listed here. But the map of the distribution of speakers makes for depressing viewing. Indeed, Ladino is, for the most part, limited to certain valleys surrounded either by Italian or by German speakers, neither of which traditionally, have had a particularly sympathy for their Romansh cousins.

Any other exotic languages: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

***

9 Feb 2013: Judith from Zenobia writes in with a small correction: I thought something was odd with this post on Ladino. Wikipedia warns us against your error most sternly: “Ladino should not be confused with the Ladin language, which is related to the Swiss Romansh and Friulian languages and is mostly spoken in the Dolomite Mountains of Northern Italy.” Ladino is (properly speaking) a Judeo-Spanish dialect or language (if you are feeling expansive) that derived from the Castilian spoken by the Jews expelled from Spain at the end of the 15th century. It is now, for all practical purposes, dead as a doornail but it was once spoken quite widely — not least in the Greece and by the Jewish community of Thessaloniki.’ Yikes, I was misled by Italian here that doesn’t make the distinction between Ladin and Ladino: and does it ever hurt when Wikipedia slaps your hand. Then Stephen D adds: You might also note: Molise Croatian, or Slavomolisano, a variety of Croatian spoken by small numbers in a few hill villages (Italian names Montemitro, Acquaviva Collecroce, San Felice del Molise: recognisably transformed into the Croatian names Mundimitar, Živavoda Kruč, Štifilić) in the province of Campobasso, well down on the east coast . The language came over from Dalmatia with refugees from the Ottoman Turks. Gardiol, spoken in the far south, in the Calabrian village of Guardia Piemontese. This is a displaced version of Vivaroaupenc, a northeastern dialect of the Occitan language from southern France and northwest Italy. Gardiol was brought to Calabria by Waldensian fugitives, heretics from the Alpine valleys, same bunch as the slaughtered saints whose bones lie scattered, etc. Some, anticipating slaughter by a century or more, fled to Calabria: they were safe till 1561, when the local capo massacred a couple of thousand as intolerable heretics. The survivors became Catholic but kept their language. I expect some long-established Italian families still speak Yiddish or Romany between themselves, but those hardly count.’ Finally LTM puts the survival of these little tongues in perspective. They all somehow made it through Fascism: Speaking dialects was made illegal under Mussolini and remained so (in Sicily anyway) until the fifties. Sicilian was the most spoken non-Italian language in Italy. “The unification of Italy in 1861 brought about sweeping social and economic reforms. Amazingly, only 2.5 percent of Italy’s population could speak standard Italian at the time of unification. Mandatory schooling and the proliferation of mass communication and mass transit had an enormous impact on the formation of modern standard Italian. Local dialects, characterized as the language of the uneducated, began to fall out of favour in the decades following unification. As Benito Mussolini and his Fascist party rose to power in the early part of the twentieth century, the push toward a common language intensified. With the goal of solidifying his control over the Italian population, Mussolini outlawed the public use of Italian dialects. Modern standard Italian was by now firmly established as the sole official language of the Italian state and its people>” Thanks Judith, LTM and Stephen and long may the little languages of Italy thrive!