Brazen Heads and Medieval Robots? March 7, 2014

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient, Medieval, Modern , trackbackIn the Middle Ages there emerged two kinds of artificial humans into the Christian imagination: the real thing needs, unfortunately, to be dismissed with Aztec jet planes and Pharonic nuclear bombs. First there were moving statues, brass and gold figures that were somtimes found guarding treasure hordes or, what might loosely be called, fairyland. These are never, in my experience of the sources, intelligent. These were the drones of faery and a possible antecedent for those early science fiction robots you see clunking through Doctor Who and post-war comic books. Second, there are the brass/bronze heads also known as ‘brazen heads’. These peculiar objects are always (or practically always) just a head placed on a table or a chair: however, unlike the brass/gold men they are intelligent and more typically prophetic; hell, one at Salamander taught magic for a reasonable price.

How do these two types of artificial humans come into being? There is no description (known to this blogger) for the dull drones, but the brass head time and time again is created by a metallurgist/magus that understands astrology and aligns his work with the heavens. It would not be true to say that every legend includes this reference to the stars, but well over three quarters do. It was a medieval given.

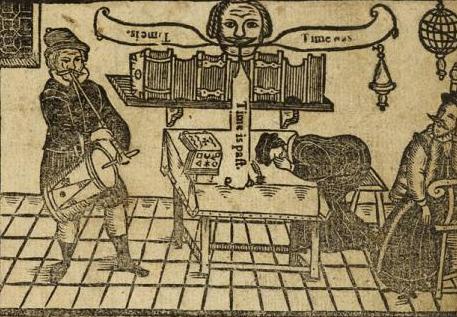

Who makes the brass head? Sometimes the author is unknown and the head is just in this or that place: a relic from an earlier age – is it possible that bronze was chosen because of surviving Roman statue heads in that metal? Sometimes the head is associated with a mythical magician Virgil (in medieval lore), for example. Most often though the brass head is connected with famous scholars, who have become, again in legend, necromancers: the great Pope Silvester II (aka Gerbinus), Enrique de Villena, Robert Grosseteste (the aptly named), Roger Bacon (pictured above with his bronze head), Albert Magnus… There is, then, a fourth category, literary personalities who meet or make brazen heads including Faust and Don Quijote and a bad tempered Sancho.

Thomas Aquinas (credited in some legends with destroying Albert Magnus’ brass head) mocked the idea that a living statue or head could be made: that’s what happens when you grow up without the daleks on TV. Others though were not so sure. Francisco de Vittoria, the sixteenth-century occultist reserved judgement and believed that the correct alignment of the stars might create unusual conditions. Does this mean that if you accidentally cast a bronze head when Saturn is riding high…?

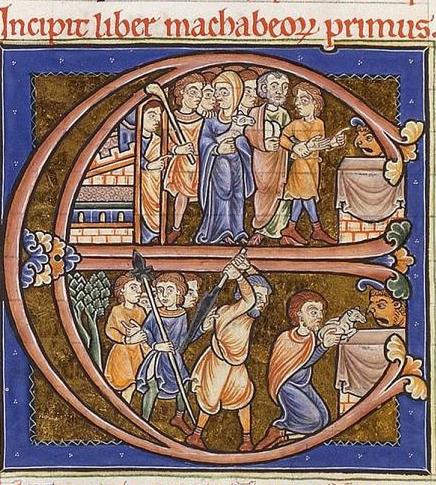

All this is interesting but it leaves one question entirely unanswered and one that relevant articles and books run away from as quickly as their paper legs can carry them. Where, in the heck, does the brazen head come from as an idea? There are no clear ancient antecedents, bar a couple of speaking statues in Greco-Roman temples and, I suppose, Orpheus (who never shut up). One possibility is that the idea was semitic and found its way into the western hermetic tradition through Jewish or Arabic texts: a decapitated golem? Certainly, Christians seem to have associated the brass/bronze head with Islam/Judaism e.g. the image at the head of this post showing a scene from the altars in Jewish Maccabees in an illuminated manuscript. Christianity made use of the talking head without external help, of course, thanks to tales of the martyrs: the most famous example being Edmund the Martyr’s nut in the brambles shouting ‘look for me over here!’ Another possibility is that the idea was Celtic: though saying something is ‘Celtic’ always seems like the last refuge of the scholarly scoundrel. Scoundrel or not Welsh and Irish lore do have several interesting decapitated heads that speak wisdom. Personally, Beach can’t get out of his head the bearded head (female?) sometimes found in inquisition accounts of medieval witchcraft: e.g. the Templar trials. But I doubt there is a connection or is that just my innner brass head speaking? For searchers the first account seems to be William of Malmesbury in the twelfth century, though William is certainly using an older source it is suggested that he changed a diabolical familiar into a brass head on his own iniative. Is the brazen head just literary invention then? Must say that such a change doesn’t really seem like William’s normal modus operandi.

Any help in the search for the origins of the brazen head? drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

The two images here come from an excellent article by Robert Mills ‘Talking Heads, or, A Tale of Two Clerics.’ Loose Heads: Beheading in Premodern Europe (2013). Honestly, what fun our academic friends have in the humanities…