Fighting the Plains Trains May 3, 2014

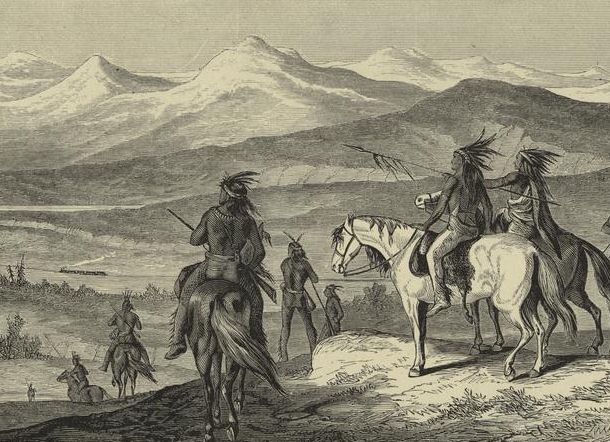

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackbackThe transcontinental railways across the American plains not only made a nation, but destroyed the way of life of hundreds of free indigenous peoples living there. The train made military control of the interior easier and, of course, the train also brought the buffalo killers: the Federal Government and its agents had long understood that if the buffalo herds were removed then the Indians themselves would not survive. Reasonably enough the Plains Indians saw the train and the whites on those trains as mortal enemies and set themselves the task of destroying the iron horse as it charged across their territories. But how can you destroy such a huge and terrifying behemoth? Our few Indian descriptions suggests simple terror at the arrival of the Iron Horse in their homelands.

A few strategies emerged. The first, and as it happens the strategy that the Indians proved best at, was to stop the railroads from ever being laid. In fact, the Plains Indians proved particularly adept at killing surveyors, who went out ahead of the large building parties and who offered soft targets: but valuable ones to the railway companies who paid dearly for lost and talented employees. Another strategy was incidental warfare against railway employees once the track was laid. There was a fair bit of this, but these were, of course, pin pricks. Another strategy still was stealing stock off trains: the companies frequently complained about ‘thieving Indians’. Then, the final strategy, and the most promising was to kill the engine itself. After all, were we given the task of stopping a continental railroad system we would all plan to derail engines and coaches.

Curiously though what was the most potentially deadly tactic was not used much by the Amerindians. In 1867 Cheyennes brought down a train at Plum Creek after taking up some of the track; and in 1868 a train was derailed at Alkali after a barrier had been built. These seem, though, to have been the only two instances where the Indians ‘killed’ one of the Iron Horses charging across their lands. Given that the railroad companies were unable to guard all the lines and given that the US Army for the most part infantry, was no match for the mobile Indians, this was an uncharacteristic oversight. Why didn’t the Indians take on the trains more often knocking off a train every couple of weeks? Was it fear of punitive missions that held them in? Or was it a fundamental misunderstanding about how the trains worked?* Were Plum Creek and Alkali just dumb luck? Any thoughts drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

*There is a haunting story about a Sioux raiding party (that I’ve not been able to track down) pulling a buffalo rope across a railway line hoping to stop a train, with predictable results.

5 May 2015: Mauro C writes: I’ve just read your article and would like to add a few things. One of the chief reasons Indian tribes did not put up a more formidable resistance against railroads is the extermination of the American Bison (Bison bison), which by the 1870’s had been massively reduced in numbers. This forced the tribes to disperse to hunt the remaining herds or to find other sources of food. As the Indians became more focused on survival, they had less resources to devote to fighting. Closely tied is the massive influx of white settlers from the West, which quickly and steadily pushed the weakened tribes by the margins. Differently from common knowledge, most tribal elders instructed their people not to sabotage railways. The reason is depressingly simple: they knew how weak they were and further conflict with the whites was to be avoided whenever possible. Of course this doesn’t mean all Indians followed their elders’ orders to the letter. Cattle raids were common (driving cattle and butchering it on the spot was a much cheaper way of feeding railroad workers than shipping food), but these were more tied to the desperate state many tribes were in after the bison had been exterminated and other game had become scarcer. There were occasional shootings of surveyors, skirmishes, and the even more occasional act of sabotage which had railway companies on their nerves.However, Major General William Tecumseh Sherman was convinced the natives posed “no real threat”. What changed his mind was the so called Bozeman Trail Slaughter of 1866. In this episode, a whole US Army company was led into a trap and killed to a man by a war band of Cheyenne and Oglala Sioux. The blame laid wholly with the company commander, a Captain Fetterman, who disobeyed his superior’s orders not to engage the Indians and foolishly walked into a trap, but Sherman was seething for vengeance. He thus ordered an increase in US Army troops stationed in the West, not an easy feat considering the best part of the US Army which had not been demobilized after the Civil War was still pinned down in occupation duties in the South. Sherman managed to increase the number of cavalry regiments, vital to cover the vast distances of the West in reasonable time, from seven to ten. Apart from two regiments made up of freed slaves (the legendary Buffalo Soldiers), which were considered elite units and had a superb fighting record, the rest were a mixed bunch and, usually, not particularly good. Most of these troopers were not hardened Civil War veterans but raw recruits or people sent to the worst assignment in the US Army as a punishment. They were poorly trained and morale was generally low. Desertion was rife and most men had only received basic infantry training before being handed a horse and sent west. Of much higher quality was an 800-strong unit of Pawnee braves recruited and led by Major Frank North. The Pawnees had usually got along well with white settlers but by 1859 they were a broken people. Epidemics and warfare with the formidable Sioux had taken the toll and they were reduced to live in a reservation in Nebraska. Frank knew the Pawnees hated the Sioux with a passion (especially the Lakota) and hence was able to recruit large numbers of men to patrol the railways. Differently from other friendly Indians serving with the US Army, they were a uniformed unit on regular payroll and with government-supplied equipment.All Plain Indians were fantastic horsemen and by supplying them with regular cavalry mounts (contrary to popular opinion much superior to the Indian Mustang), North had at his disposal a formidable unit to patrol the railways. These Pawnee Scouts, as they were called, proved to be incredibly efficient at protecting railroad parties.’ KMH writes, meanwhile, It should be remembered that the Amerindians were composed of many different tribes, each with its own perception of the white man menace. Some had been already rendered unable to engage further hostilities. For effective resistance a “charismatic” leader was needed, but they were few and far between. Sitting Bull united the Lakota tribes to defeat General Custer though overwhelming numbers; there was Geronimo who was a legend in his own time. And there were a few other famous leaders. But the divisions between the tribes ran so deep that a general united uprising was impossible as a practical matter, so that thwarting the railways wasn’t possible. Don’t think I am trying to railroad you with this explanation.’ Thanks KMH and Mauro!

7 May 2014: Chris S writes in: The railroad certainly received its share of harassment. Livestock was continuously rustled by tribal raiders, who also boldly shot up work crews and terrorized isolated station towns. Particularly vulnerable were route surveyors, who struck out on their own ahead of the work crews — and sometimes paid for it with their lives. Twice, Native Americans sabotaged the iron rails themselves. In August 1867 a Cheyenne raiding party decided they would attempt to derail a train. They tied a stick across the rails and succeeded in overturning a handcar, killing its crew of repairmen, with the exception of a man named William Thompson. He was shot and scalped, but lived to tell about it as he traveled back to Omaha with his scalp in a pail of water by his side. In 1868 a group of Sioux created a more intense blockade, upturning both rails and piling wooden ties in between them, then tying the whole thing together with telegraph wire. The resulting wreck killed two crewmen, one of who was crushed beneath the train’s boiler. ‘Official confirmation of the story of how Yaqui Indians derailed a train between Hermosillo and Guaymas and burned sixty persons in a car of hay, was received today by the State department. No foreigners were reported killed. There is no telegraphic communication between Guaymas and the Yaqui valley.’ Reported September 28th, 1915 ‘Those coming up from Sonora Tuesday state that it is reported that within a few days there have been found in the country outside Minas Prietas, Torres and Hermosillo, twenty four dead victims of Yaqui hatred. The trainmen on the Sonora railway are becoming apprehensive that the Indians may resort to derailing night trains and massacreing the passengers, and they hope for a day schedule, so they may have a chance to see any obstruction which may be placed upon the track and avoid it.’ Reported January 28th, 1905 Meanwhile, Ricardo an old friend of this blog writes: I would point to the film from Jim Jarmusch, Dead Man. The gratuits scene in the beggining of Bison shooting from the train is very on topic. The film is also highly regarded by its protrait of north-american indian culture and living.’ Thanks Chris and Ricardo!