How to Train a Griffin! June 6, 2014

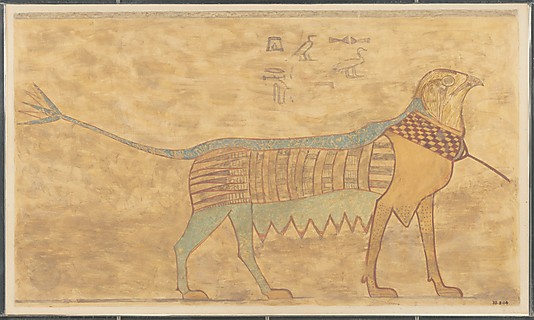

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient , trackbackBeni Hassan is a collection of ancient Egyptian tombs in central Egypt. The tombs there have many precious illustrations of day-to-day life under the Pharoahs. And one of the most curious images is that above from the tomb of Khety (eleventh dynasty). Reader, what are you looking at? No, idea? Well, there is little doubt that this is a griffin (hawk’s head and a dog’s body), a fairly common creature in Egyptian iconography, one probably borrowed from the north of the Mediterranean or the Levant, but one that was entirely naturalized by the second millennium BC. The problem is that here the griffin is portrayed as, say it quietly, a pet with a leash on its neck and the text above says: ‘Her name is Saget’. What do we do with this domesticated monster, which may, to judge by the colours have had folded wings? Two possible scenarios jump to mind.

1) Syrian merchants had brought a baby griffin down the trade routes from Scythia and the creature had, at least briefly, lived with Khety. However, after a fight with a resident dragon chick, the griffin died and had to be buried under a pyramid.

2) Relax, crytozoologists, this is a mythological creature that has been included in a wall painting as a pet. But it is a joke! Didn’t you know that the ancient Egyptians had a great sense of humour? In fact, their shades are laughing at you now.

If you don’t like either of these explanations, and Egyptologists do seem a little antsy about the second explanation, don’t panic. A third explanation has also been offered. Namely that:

3) A dog bitch was dressed up to look like a griffin and spent her time bumping into things because she couldn’t see properly through her hawk mask and her straw lotus tail kept knocking glasses off the parlour table.

Perhaps in an earlier life you threw an ivory Egyptian magic wand across the courtyard and shouted: ‘Fetch, Saget!, Fetch!’

In truth, I like number three not because I think for a second that it is correct but because an Egyptologist seriously suggested it.

Other thoughts? drbeachcombing At yahoo DOT com

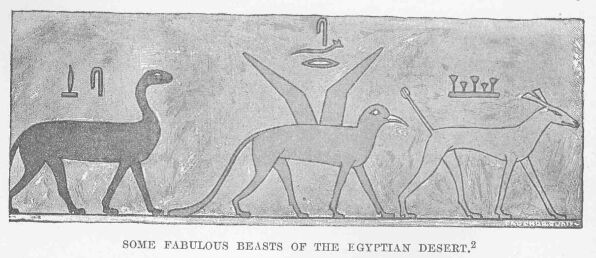

Included here is a more typical image of a griffin (middle), in association with other fantastic Egyptian animals, out in the wastes: which would you least like to meet in the middle of the night? The image is roughly contemporary and comes from the same site: though not the same tomb. Note lack of leash!

26 June 2014: Judith from Zenobia writes ‘I come rather late to your griffin post. Far be it from me to critique what is written tongue-in-cheek but two points that your amused/bemused readers might wish to know. First, though I won’t swear to it, I doubt that the image and idea of the griffin is borrowed from Mesopotamia or the Levant. The Egyptian winged griffin goes back to the predynastic period (ca. 3150 BCE) where it appears on the so-called ‘Two Dog Palette’ in the Ashmolean Museum and on a gold leaf knife handle from Gebel Tarif. This is, of course, a period with much iconographic influence from Mesopotamia; for example, the snake-lion. Still, I don’t know of equally early griffins (bird-headed lions, with and without wings) from those regions. Second, Middle Kingdom griffins are given three different names: (a) sfr, perhaps coming from a Semitic language meaning something like ‘on the mountain’ or ‘in the desert’, a beast shown with wings hunting wild animals in the desert; (b) tsts, winged and wearing a kind of (horned?) headdress, war-like and trampling enemies, which becomes the royal griffin (not always with wings) from the 5th and 6th Dynasties onwards; and (c) the z3gt-griffin from Bene Hasan and El-Bersheh — both near the Egyptian-Canaan border: that is your Saget, and both examples are probably wingless and wear collars. ‘Fetch Saget!’ is an unlikely command as the full text has been restored (rightly or wrongly) — to read z3w nzt r rn=s, ‘Protector of the throne in accordance with her name’. Rather a mouthful for a pet’s name. Incidentally, female griffins do appear from time to time and pop up again on Minoan Crete: once even shown with baby griffins. So now we know how they procreate!’ Thanks Judith apologies that this went up so late!