Were Ancient or Modern Soldiers More Likely to Die? June 11, 2014

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient, Contemporary, Medieval, Modern , trackbackSoldier, forget principle, forget country, forget pride, forget hate: your one aim is to survive, with or without your legs. Now ask yourself this: given that you want, at all costs, to live would you prefer to fight in WW2 battle or a battle in the Punic wars in antiquity?

Perhaps the first thing to say is that if children ‘play’ battles with plastic soldier then most will die in the melee: something similar happens with films and computer games. But one of the most extraordinary things about real battles is how few men-at-arms are actually killed. At bloody Gettysburg, for example, about eight thousand died of the 160,000-170,000 who fought. At bloody Waterloo perhaps ten thousand of the two hundred thousand who fought perished. This does not mean that battles are safe, the odds of serious physical and mental injury is there at all times (there are lesser deaths, and generals are concerned with these while we, given the exercise at hand, can ignore them). But battles are not quite the game of Russian roulette that we sometimes envisage; crudely there are ten or twenty chambers and one bullet not six chambers. There are exceptions, of course. British frontline troops heading towards German machine guns at the Somme on 1 July 1916 saw murderous casualty rates, but again it was not as bad as our grandparents tell us: of 100,000 British and Dominion troops attacking on that tragic day ‘only’ twenty thousand were killed. Then, it goes without saying that there are concentrations in the killing. Soldier, don’t have anything to do with George Pickett, avoid cavalry, and do not ever become a non-commissioned British officer etc etc.

How much better or worse were things in the Middle Ages or Antiquity than these modern examples? On the one hand, weapons were less lethal – though never underestimate the killing power of a pissed off Welsh archer. But, on the other, the Geneva Convention and Enlightenment simpering about ‘rights’ had not begun: putting your hands up did not always work (whereas of course today…). The biggest problem, though, is not this contradiction but rather the lack of reliable data. Data is not a breeze even for the World Wars (I played around with the numbers for Stalingrad this afternoon), never mind for, say, Viking fights in tenth century France or a Renaissance scrap in which only one person was killed (a previous post, a previous day). Take the Battle of Falkirk, a nasty little number involving the English and Scots in 1298. The Scots had 6000 men and lost 2000, the English had 15000 men and also lost 2000: or so Wikipiedia claims… But, first, can we trust the numbers of combatants. Some records push the invaders up to 80,000: Wallace’s Scottish army has been claimed, meanwhile, to be as big as 25,000. Perhaps the only thing that we can be sure of is that the English substantially outnumbered the brave Scots. Second problem, can we trust the number of the lost? No one was particularly interested in death details and the rapid chase that followed Falkirk hardly suggests ideal condition for counting. Third problem, what is meant by ‘lost’: there were presumably the wounded there as well?

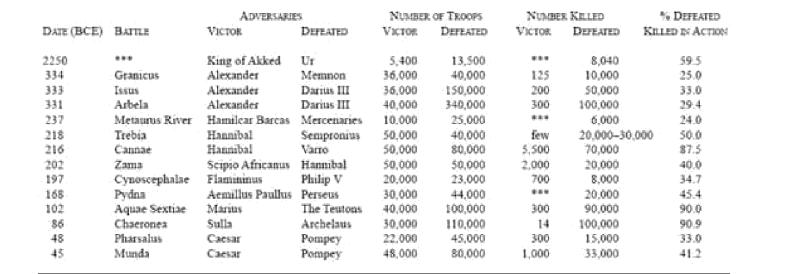

This is just a reminder that any pontificating about pre-gunpowder casualties may be inherently flawed: see the chart here (1) of ancient battles – can we seriously believe these numbers? And, in fact, what is fascinating is the disagreement among historians writing today. There are those (e.g. Gabriel, Great Battles of Antiquity, from which the table is taken, p. 33) who claim that modern weapons are more powerful and kill more people period: this is surely the intuitive answer. There are others though – for example, T.N.Dupuy – who have got all counter-intuitive. Modern weapons have meant, save some embarrassing exceptions like British strategy on the Somme, greater dispersion and this has saved lives notwithstanding the greater killing power of modernity. The arguments are intriguing and probably have a lot to do with a steeper difference between victor and loser in pre-gunpowder wars; and the contrast between organized and unorganized fighting. Crudely, if you were the captain of a thousand Gaulish warriors who went into battle without armour but with lots of body paint against a Roman century or two, then by the end of the day a LOT of your men would be dead, enough to make the Somme look like a Sunday brunch in the happier half of the 1990s. Going back to the original question, the choice between the Punic Wars and WW2 would probably depend on which side you were on in the third century B.C. and, more importantly, which battle was being fought.

Perhaps these factors mean that generalizations are just impractical? Any other thoughts: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

11 June 2014 Tacitus from Detritus writes: If your simple and laudable goal is to survive, then go for the modern way of war. Up until perhaps World War I ( any votes for Crimean?) more soldiers died of disease than from enemy steel. Or lead. You are just as dead from “the flux”. A Civil War encampment with its crude wells and privies was probably more dangerous than most Civil War battle fields. Nathaniel backs this up: Your discussion of the likelihood of death for ancient vs. modern soldiers overlooks a couple of issues: 1) Disease. Up until the early 20th century more soldiers were killed by germs than by swords or bullets. Per Wikipedia, about 2/3 of U.S. Civil War soldier deaths were the result of disease. Even in WW 1, more U.S. soldiers died of “other” causes than from combat. Figures from earlier times are even more lopsided. 2) In modern armies, the percentage of soldiers that actually see combat is low, since roughly 90% are in various support functions (probably the main reason behind the expensive attempt to contract out many services). Earlier armies had much higher percentages of combatants. My vote: modern army anytime. Thanks to Tacitus and Nathaniel. Note though that the Somme figures above include just combatants and that in legalise you have only to survive to evening so disease is not that big an issue. I also wonder how many more men died from disease in ancient times than modern? Thanks!

23 Feb 2017: Neil writes ‘Not being at Towton (1461) would help. I have mixed feelings about the archaeology and osteology of some of the participants in Tow. The injuries are horrific and may have been retribution not in the heat of battle. You may be able to access this documentary, which demonstrates that at least for some (Towton 16) astonishingly effective medical treatment was possible (c.22 mins ff)

30 Mar 2017: Kevin B writes: Interesting article. I wonder though if its not a little sterile to consider only combatant troops. Undoubtedly they are the sharp end of the stick, but a feature of modern warfare is the development of artillery into a cornerstone of tactical planning. Not only did non-combatant troops become more vulnerable and targets, but so did civilian populations. Air power and bombing raids from Guernica to Vietnam ought to be considered as well. Is there an ancient analog for the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Perhaps the sacking of Carthage? Ironically, while it may have become “safer” to be a combatant soldier when looking at contemporary vs. ancient warfare, warfare itself seems to have become exponentially more deadly.

James H, 29 Jan 2018: What seems to be missing is due to advances in medical treatment you have a much higher survival rate now, but in much worse overall shape (lost limbs, eyes, internal disruption, etc). I look at it this way; would I prefer the possibility of death by being blown to pieces or chopped to pieces in close quarters by crowds of men with essentially large butcher knives.