Crossing the Rhine and Surrendering: 1793 February 19, 2015

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackback***Stephen D sent this one in: thanks!***

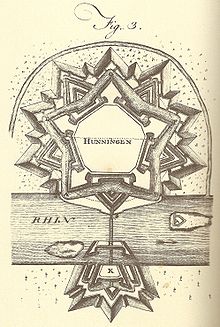

The following post describes an attempted French invasion across the Rhine at Huningue, just to the north of the Swiss border in September 1793. It goes without saying that amphibious operations are hellishly difficult in modern times.

The Huningue operation began with the decimation of the officer ranks. The commanding general was arrested because he still had the fleur-de-lys on his sword, the symbol of the defunct Bourbon monarchy, on his sword. Then another superior officer, who happened to be German, resigned. The men on the ground had been told to invade Germany in hours rather than weeks and without the upper ranks to get in the way : ‘they set about their allotted task with praiseworthy republican enthusiasm.’

Since Germany was located on the far side of the Rhine from Huningue, it was obvious that no invasion could be mounted without the use of suitable water transport. None happened to be available at the time (most of it was away at Colmar being repaired), so the construction of four large invasion rafts was ordered, each sufficient to take 100 soldiers and a cannon. Military reinforcements were also requested, but none could be found except for some peasants conscripted on the spot, but who could not possibly be armed, trained, clothed, let alone paid, within the few days available for the operation. At least some experienced boatmen could be pressed into making the crossing which, despite inevitable delays, was finally set for dawn on 17 September. The boatmen, however, took one look at the unseasoned timber of the badly leaking rafts, and declared they would not set foot on them. They had to be forced into doing so at gunpoint, and even then only 200 soldiers (without cannon) could be fitted into the three rafts that could actually be launched. Knee-deep in water, but shouting ‘Vive la Republique’ to the applause of a patriotic crowd, the whole lot then cast off to fulfil their destiny as liberators of Germany.

There is something touching about soldiers being forced into sinking river boats at gunpoint and who other than the French would then take up patriotic slogans? What a people…

As they came in sight of the enemy’s batteries they were met with a hail of roundshot, all of which mercifully missed its mark. However, the first salvo caused the soldiers to duck instinctively, en masse, thereby upsetting the delicate trim of their craft so that water sloshed into their cartridge pouches and spoiled their powder. Nevertheless, they did actually succeed in landing on German soil, even though the rafts themselves could not be secured to it due to an administrative failure to provide any mooring lines. Most of the soldiers then set off to fight the Imperial army although, since they had no usable powder, they quickly decided it would be more prudent to surrender themselves to the nearby Swiss authorities, who duly disarmed them and sent them home. (Paddy Griffiths, The art of war in revolutionary France, 66)

Any other amphibious cockups? drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

24 Feb 2015: Ben H on another amphibious cockup ‘Ben H writes in I’m not sure if this counts as a disaster, probably more of an embarrassment. This is from the memoirs of Alexander Verestchagin, a Russian cavalry officer who took part in the 1880 Russian campaign against the fortress of Geok Tepe (near what is now Ashgabat, Turkmenistan), my notes are in brackets. “I ride through the waterless, sandy wilderness to Yagly Olum [around 40km inland from the Caspian Sea coast, close to the border with Iran ]. This little place is situated on the banks of the Atrek, a narrow stream, from fifteen to twenty feet wide [also, barely more than ankle-deep]. It flows between high, steep banks, overgrown with small bushes of saksaul, the only vegetation to be met with in the whole of this oasis. It is necessary to add that up to the time of this expedition the river Atrek had been but little explored, and Skobelev [General Mikhail Skobelev, commander of the expedition] had been assured that small steam-cutters could navigate the Atrek. This was very important in view of the difficulty of ferrying over loads [through the desert to Geok Tepe]. Several steam-launches, a detail of sailors, under the command of two officers, and four mitrailleuses [machine guns, probably hand-crank Gatling guns] were placed at the disposal of the commander of the expedition. But the Atrek turned out to be so shallow and insignificant that the launches had to be dragged several scores of versts by hand [presumably in the hope of finding deeper water upriver], and afterwards dragged back to Tchikishlyar in the same manner.” Earlier in the 19th century the Russians had tried to operate a steam gunboat on the Syr Darya River with similarly mixed results. The first part of the operation involved buying the boat from a shipyard in Sweden and sailing it to St Petersburg. They then had to dismantle it and transport it by train to the upper Volga where it was reassembled and refloated. After sailing it down the Volga to Astrakhan they had to dismantle it again and load it onto wagons for the trip across the desert to the Aral Sea. They then reassembled it for a second time and sailed it to the mouth of the Syr Darya, where it promptly ran aground. With some clever piloting they managed to refloat it, but it quickly became apparent that only about 100km of the Syr Darya was navigable, and then only in the spring. Furthermore, most of the area was already comfortably in Russian hands already. Unsurprisingly, having been taken apart and reassembled twice on its way down, it wasn’t the most reliable ship and the 3500km between it and its home shipyard meant that spare parts were a long time coming.’