Emperor Stars in Anti-Colonial Play June 20, 2015

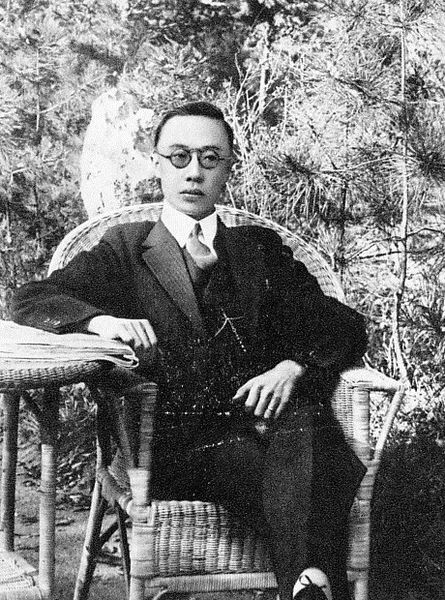

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackbackPuyu (obit 1967) has gone down in history as the last Chinese emperor, not including of course Mao and his successors, and what a life he had. Brought up in the Forbidden Palace he was perhaps the most spoilt boy in the world: having servants beaten for a whim; this perhaps made up for the face that he had no real governmental power. He ‘ruled’, for a time, over a hollowed out country that was being exploited by warlords. He fell into Japanese hands in 1925 and would stay in their power for about twenty years. In 1945 he fell into Soviet hands – talk about the frying pan into the fire… – then finally into Chinese communist hands in 1949 – the fire into the vaulted depths of hell? The Chinese communists must have been desperate to bury a bullet in Puyu’s head, but someone somewhere decided that the last Emperor might actually be a propaganda coup waiting to happen. (An aside: communist violence in China seems much more arbitrary than in Stalin’s Soviet Union or perhaps it just operates according to rules imperceptible to western capitalists.) Puyu, in any case, found himself in the Fushun War Criminals Management Centre where he spent ten years ‘getting better’ or as it is known in the west, being brainwashed. He finally left the camp in 1959, aged 53, and worked in a botanical garden in Peking. Beach hopes he was happy: he survived for a further eight years.

Puyu’s communist-sponsored autobiography includes many extraordinary scenes, but the following is Beach’s favourite. In the correctional camp where Puyu was staying it had been decided to put on a play against the evils of imperialism and more particularly the Suez Crisis. The play was set in the British parliament with two rows of chairs representing the government and opposition benches and Old Jun, a one time crony of Puyu, had been cast as Selwyn Lloyd, conservative foreign secretary, who had the thankless task of defending Britain’s improvident decisions in Egypt. ‘Since he had a big nose he was really the only M.P. who looked like an Englishman.’ Puyu who had taken some care to dress the part and who always looked dapper in a suit had been cast as the most left wing labour MP possible, interestingly not named. He stood up in the middle of Selwyn Lloyd’s speech, forgot his lines and shouted at the Conservative benches: ‘No!, No! No!’ Then, the words he had practised so hard returned to him. ‘Mr Lloyd please don’t continue your tricky defence. In fact, this is a shambles, a shambles, a shambles!’ And, finally, to general applause from the audience, the Labour benches chanted: ‘scram, scram, scram…’ and poor old Selwyn Lloyd ran off the stage. Parliamentary democracy reduced to Chinese pantomime. Earlier in his career Puyu had refused to meet a Swedish prince because the man had been photographed with an actress in the newspapers so threatening Puyu’s imperial dignity, now he was wowing the crowds in a correctional facility by ad-libbing ‘no, no, no…’ Puyu had won the victory over himself, he had come to love big brother.