Greeks in Buddhist India? March 20, 2016

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient , trackback

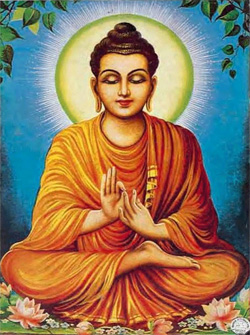

Basnagoda Rahula argued in his doctorate, written in sometimes shaky English, but full of fascinating ideas, for wholesale Indian influence on Greek culture and above all, Greek philosophy. The arguments are exciting but annoyingly insubstantial: no fault of BR, of course. It would be exciting to have some kind of outside input into the beginning of Greek thought, which seems, sometimes, to be lying in the cradle with no parents to tend it. Here is one of his several intriguing references. This one is exciting though because it goes the other way. It seems to suggest Mediterranean input in Buddhist thought.

The Buddha: ‘What do you think about this, Assalayana? Have you heard that in Yona and Kamboja and other adjacent districts there are only two castes, the master and the slave? And that having been a master, one becomes a slave; having been a slave, one becomes a master?’

Assalayana: Yes, I have heard this, sir. In Yona and Kamboja… having been a slave, one becomes a master. [334]

BR goes on to suggest that Yona refers to Ionia, in other words the Greeks: this is, in fact, uncontroversial and we’ve come across this usage before on this site. Kamboja is a mysterious term, but BR wonders whether it might not be Persia.

In contrast, the Persian name for both Carabyses I who initially helped build up the Persian empire and Cambyses II who expanded the empire was Kambujiya, and the Buddha could have used ‘Kamboja’ to mean the land of Kambujiya. This usage also corresponds with the Buddha’s own usage of Kosala to mean the former Indian state ruled by the Buddha’s contemporary king Kosala. Kambujiya, who conquered Egypt, was a contemporary of the Buddha [controversial dating], and it is very well possible that the Buddha used the word Kamboja to indicate the territory of Kambujiya. [326-327]

It goes without saying that the idea that a slave can become master or a free-man slaves works very well for the Greek world: India, of course, had the caste system. The main problem is the dating of the text. It was probably written in the third century BC after the time of Alexander. In other words there is no guarantee that these are reliable Buddha sayings, relating to fifth- or just possibly sixth-century realities. Still, always a frisson of excitement when two distant parts of the world get yoked together even if it is just in a talk between prince and disciple. It is even more impressive when the information given is essentially correct.

Other wrong place conversations: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

25 Mar 2016: Mauro C writes in ‘I was recently reading your article on Greeks in Buddhist India: and was reminded of my studies on the religions of Central Asia, of which Buddhism is arguably the most important until the arrival of Islam in the VII-VIII century AD. In the earliest phase, Buddhists texts were apparently not written down but passed down orally from teacher to pupil: the earliest written texts we have come from near Taxila and have been dated to the early I century AD. It’s obviously well possible they were written down well before this date, but we lack any solid proof apart from inscriptions. Among the earliest known texts which came to us is the Milinda Panha. This is a dialogue on Socratic style between the Kashmiri Buddhist sage Nagasena and the Graeco-Bactrian ruler Menandros I Soter. While all versions we have available have been written in the Christian Era, the text itself is older and had been dated to Menandros’ own reign (165-130 BC). Albeit the text deals with Buddhist themes dear to the Sarvastavadin school, it’s structured like a typical Socratic dialogue so it’s possible if not very likely the original writer had been influenced by Greek works of philosophy. Probably one of the most important Greek influences over Buddhist thought is the representation of the Buddha in human form. This tradition originated in Gandhara, either under Menandros himself or his immediate successors, and spread like wildfire throughout all the Buddhist world. The originals were a peculiar blend of Indian and Greek art and are referred to as the Gandhara Synthesis or School. The earliest known evidence of Mahayan ideas is a late I century statue of the Gandhara School of the Buddha flanked by two bodhisattvas with an inscription mentioning the transferal of merit. Finally a note regarding the immensely popular figure of the Maitreya, the Future Buddha. While it was long believed to have been inspired by the Christian or Jewish Messiah, in reality all three figures were inspired by the same source, the Iranic/Zoroastrian Saoshyant, the future savior. Hope this is useful to you and your readers.’

25 Mar 2016: JV writes ‘Does “having been a master, one becomes a slave; having been a slave, one becomes a master” refer to reincarnation? Slaves (who perhaps mostly are in no position to do serious evil, and thus move “up”) the scale) are reinacarnated as masters (who perhaps do evil in enslaving, and so move “down” in reincarnation), and vice versa?’