Review: A Word Geography of England April 3, 2016

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary, Modern , trackback

When Beach was a little tyke (boy) he used to run out to lek (play) and then he and his friends would go to the shop to buy spice (candy): trousers were ‘togs’ in those not so halcyon days, and missing school was ‘skiving’. Dialect is dead in England (save perhaps in the north-east), but there are still fossils from the regional grammars and vocabularies that survive in day-to-day life: though Beach doubts that tykes in his home valley lek or eat spice today. Yet this is a world that is not that far gone. Beach was lucky enough to know some pure dialect speakers as he grew up; and many semi-dialect speakers. And as recently as 1979 the police were able to decide which town a fake serial killer had come through on the basis of his accent and word choices when he spoke on tapes that he sent in to the authorities: this kind of pin pointing would be simply impossible (outside Britain and Ireland) elsewhere in the English-speaking world.

Luckily before the last dialect speakers were dropped into time’s paper shredder, some intervened to catch the last words being muttered. The project was known as the Survey of English Dialects and was a multi-volume effort under the direction of Harold Orton. The combined works remains one of the great achievements of twentieth-century scholarship, one that fits easily into the same bracket as Encyclopedia Britannica and the Oxford English Dictionary. Interviewers were sent out to over 300 destinations and interviewees were given about eighteen hours of interviews: sometimes divided up between interviewees, sometimes undertaken by one man. The interviewees were invariably men in traditional professions; women, it was felt, were too attentive to social mobility and would try and give up their dialects whenever possible.

Now at this point some readers will be looking for out. ‘Dialect is interesting perhaps, but I do not have the 1200 dollars necessary to buy the whole series.’ And this is precisely why Beach decided to write this post. In 1974 Orton and Nathalia Wright, published a kind of summary of their work for the general reader entitled: A Word Geography of England – is there any greater sign of scholarly nobility than an attempt to communicate with the public at large? Not only does this currently retail for one pence on amazon.co.uk, it also does not have many words in it, for the entire book is made up of maps (just over 200) showing what the SED team found.

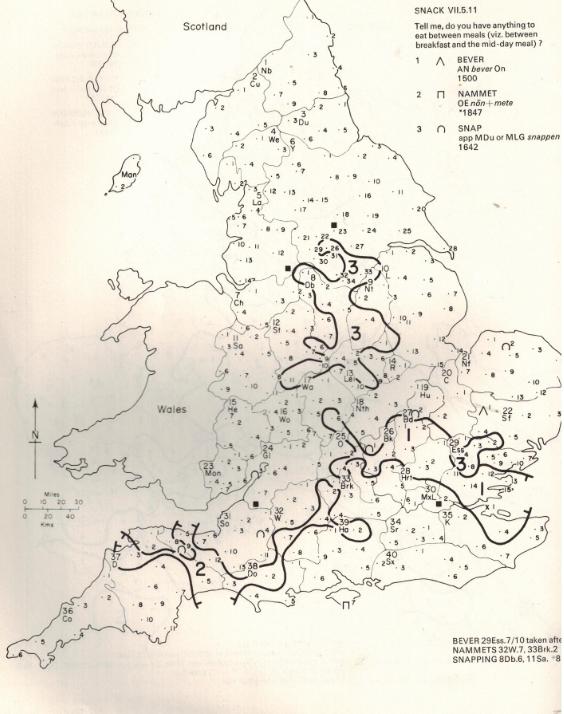

So in most of England dialect speakers say ‘dig’ to the question ‘What do you do in the garden with a spade?’ But in Lancashire and Northumbria the say ‘delve’. Whereas in Westmorland and Cumbria and Lancashire ‘beyond the sands’ they say ‘grave’: as in ‘grave me a hole.’ To Beach’s delight the editors don’t waste any time with vowels (which is vital but tedious) and instead concentrate on meaning. We have the way you say ‘yes’ (the English oc/oil): ‘aye’, ‘yaye’ or ‘yes’. We have words for ear-wigs; we have words for snack (see image above, with words from Anglo-Saxon, Norman French and Dutch) and to Beach’s very great satisfaction we have the words for candy, including his own dear ‘spice’.

Other unusual books: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

Ruth B writes in, 30 April, 2016: Really Beachy, how could you? Dialect is alive and living in the world, though most people don’t have the ear to hear it now. I’m not talking about a foreign language speaking person moving to another country, either. That’s something else altogether! It’s very obvious in much of America because our people come from everywhere and most will assimilate in a few generations, adding and subtracting their own bits to the “English” form that we speak. I have a terrible time understanding many people from the western coastal states, particularly because of the different forms of words we use. And don’t even get me started on California’s beach boys and Valley Girls, and Seattle’s grunge crowd and hipsters. Even within each state there will be variations of words, and the larger the city in a region you can have a variation from one side of town to the other. The side of the city I grew up in was, and still is to some extent, considered a rough area, however urbanized it may be. You also have the differences between city and country. I had to learn a whole new set of slang from the city I grew up in when I went to a small town country college, and the cow college my husband went to a few years later. Nowadays, of course, there will be ethnic slang terms mixing in, terminology from different careers and jobs, slang terms from one part of the country moving around because of TV and movies. It’s still a very vital part of our language, even if the terms are different from what we grew up with. Many terms are generational and regional, pop and cola mean the same thing, but you will hear them used in different areas (That’s the most common one I can think of.). Many people say Kleenex when they refer to any brand of tissues, but we all get it, an example of country wide slang usage. For me, accents from the different parts of the country, and sometimes other countries, are the most telling thing. Too many years of watching British TV over here and I can tell where a lot of people come from and possibly their social status! I catch my Okie accent switching back and forth a lot, sometimes reflecting my mother’s family from Kansas and my father’s Oklahoma ancestors, with sometimes a little German influence thrown in, for confusion. In Oklahoma we refer to grocery carts as “buggies”, but here in Washington state they are “carts”. You should see the looks I get on that one! Texas calls them buggies, and I believe Kansas and Arkansas do too, all adjoining Southern states. I don’t know that it would be possible to do such a geography now, because language changes much faster, as I said above for various reasons. Perhaps accent will become more important? And I still think it takes a particular “ear” to catch a subtle regional difference.

Bruce T Being raised by two grandparents born at the turn of the 20th century, I was very aware that the way they and their siblings spoke was much different than the way my young school friends and many teachers spoke. I ended up in a speech class for a couple of years due to the fact many of them couldn’t understand what in the Hell I was saying. When my Grandmother was dying, circa 1966, she liked to have the brother of my Aunt by marriage stop by to talk to her. Why? He spoke what she referred to as “Old Virginian”, the dialect of her parents and grandparents. They would talk and joke for hours. You can still hear it, but now it’s more a dialect of old upper class families than a general one, and many of the cruder terms have disappeared. I suspect the reason the dialect has lasted there is the these people generally attend the same private schools, universities, and as adults associate and marry in the same circles. The accent and vowel sounds give it away more now than the terms themselves. I know it in an instant when I hear it. The television preacher and former Presidential candidate, Pat Robertson is a prime example of someone who speaks the upper class version. Unfortunately, the more plebeian form mostly died out during the great industrialization and urbanization of the 20th century and the advent of radio and television. It’s spoken in few rural areas, but even there it’s not common. I miss a lot of the terms. Whereas many Brits might use “village bicycle” as term for a girl of loose morals, the old word here for such a girl was “weed monkey”, ie; a girl who goes out in to the tall weeds to romp with the boys. By the way, “togs” used to refer to nice clothes in general here, more of an outfit like a suit or the better clothes you wore to school on picture day. Everyday pants were “britches”.

Alastair writes: Hi,

Having recently read your article entitled, “A Word Geography of England” I think I should point out that dialect is alive and well in my part of the world. Indeed my neighbour although admittedly he is 96 speaks dialect and no other version of English it seems – Lincolnshire dialect to be precise.

Please check out this video it is a Sat Nav in Lincolnshire dialect there are other videos of this online but at the moment struggling to find them;

Here’s another funny story;

Genuinely there are many characters like this in East Lindsey in fact it seems more often the case than not in the villages but of course it will decline due to various factors.