Surrender, Secret Weapons and the Nazis May 15, 2016

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackback

Anyone but a fool or a wishful (?) thinker would have understood that the Third Reich was doomed by early 1945. Yet, as we all know, the Nazi high command kept shooting. Tanks were sent west for the Battle of the Bulge and German soldiers frequently fought to the last man a week after Hitler had gone to a worse place. Why? The Nazi Party and the German Army had both taken their own ‘stab in the back’ myth a little bit too seriously: and simply refused to consider surrender rationally. Hitler’s claims that Germany had failed him make a lot more sense when coupled with his determination to destroy Germany as the Soviets and Allies pressed in. But in other sections of German society, and in occupied or friendly territories another motivation proved important, the belief in Germany’s secret weapons.

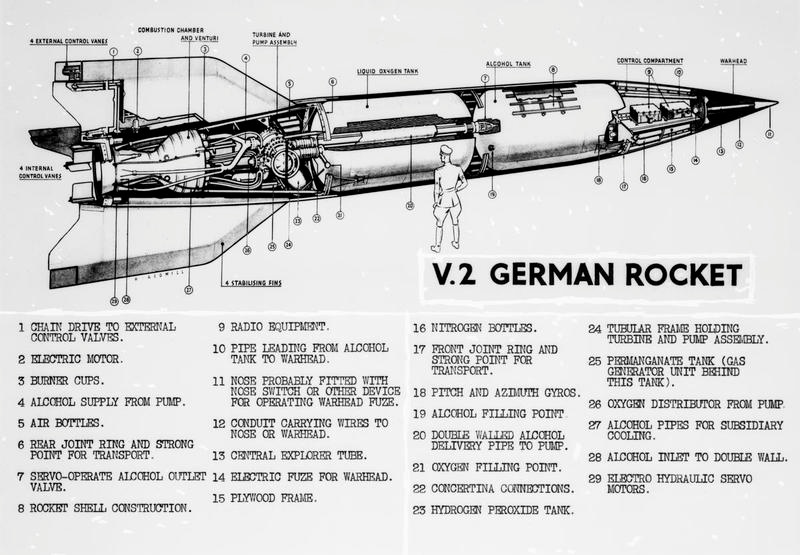

The idea that Germany had a series of ‘secret weapons’ ready to unleash on an unsuspecting world was only very partially true. Germany had had, of course, its impressive rocket bombs: but though these destroyed a good deal of acres of housing in the south-east of England, they were not in the end enough to bring the UK to its knees or, indeed, anything close to it. (Arguably they did more damage than good to Germany by redirecting scarce war resources away from normal aviation production). There were also advances in plane design, but nothing that Germany could get into the air in sufficient numbers. Then, there is the old canard of Germany’s atomic bomb program: something that again did not, thankfully, get off the ground. Yet the fact remains that as the war ground towards its inevitable end Axis members and friends spoke increasingly about these ‘secret weapons’. In fact, the talk about the secret weapons proved far more effective than the secret weapons themselves.

For example, there was much talk about the secret weapons in Salò, the Fascist puppet regime in northern Italy. Giorgio Almirante the postwar fascist politician and long-time head of the MSI, is remembered at the end of the war as alluding constantly to these mysterious weapons. Franco, in Spain, continued to talk about a German victory up until the late spring of 1945: he seems to have believed that the Germans had learnt to harness solar energy for military ends. In fact, one Spanish newspaper, Informaciones claimed, on Hitler’s death, that Germany had chosen to spare Europe by not using these secret weapons! (So uncharacteristically good of Adolf). Internal Reich memos also recorded that one of the few effective tools for public opinion was the claim made on radio and in the press that Nazi secret weapons would turn the tide of the war.

Beach has often wondered what you do in an army that has clearly been defeated but that has not yet been beaten. How, for example, did Lee manage to keep his men fighting into 1865? The Nazis seems to have stumbled on a particularly effective instance in World War II. Parallels: drbeachcombing At yahoo DOT com

20 May 2016: Leif writes: The Nazi end-of-war faith in secret weapons should be interpreted as part of the ‘Produktionswunder’, which promised that an vastly outmanned Germany could still win the war based on superior technology and industry. Mit Blick auf de Kriegswirtshaft und die stattlichen Interventionen des NS-Regimes wird nicht selten von einem ‘Produktionswunder’ geschprochen, welches vor allem auf die Reorganisations der Kriegswirtshaft unter Speer zurückgeführt wird.’ [Kleinschmidt, Christian. Technik und Wirtschaft im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. 2006. p 52. English translation follows:] ‘In view of the war industry and the state intervention of the National-Socialist regime, a “production miracle”, was not infrequently mentioned. This term is mainly attributed to the reorganization of the war industry under [Albert] Speer.’ By 1944 the Nazis were clutching at straws, and by 1945 secret weapons were the only straw left. But is it unusual for people facing defeat to hope for miracles, and weren’t these secret weapons a 20th century equivalent of divine intervention? More interestingly, are there historical examples of all-but-defeated peoples hoping for miracles– and getting them?

James H writes: This a phenomenon known and talked about for a long time (especially in the military). The closest anyone has come to it is a description of a strange amalgamation of faith, duty, and resignation. To be blunt, no one really knows why people do this, but they do (history is littered with examples), it just seems to fall into the realm of the divine (for better or worse).

If you ask most combat leaders why their men followed them, almost all if truthful will answer “I don’t know.” And neither do I.

Bruce T: I mentioned Sun Tzu’s concept of “death ground” in an earlier post, the idea that if we’re going to be annihilated we might as well take as many of those other bastards with us as we can. It worked spectacularly for the Athenians against the Persians and again for Henry IV at Agincourt. The Germans were fighting for their existence as they saw it, as was the Confederacy. Two would be propaganda. The Germans were convinced they were just one victory from winning the war at best, or a negotiated peace at worse. In the case of the Confederacy, the idea that the latter was still remotely achievable and the latter were factors that kept hope alive.Finally there’s pure chauvinism, the idea that the subhuman other could defeat the superior order was beyond conception. I’m surprised you didn’t throw the Japanese into the mix. The concept of divine nation led by a God Incarnate suffering defeat is the stuff of many books. In a way the elite of the South didn’t lose the Civil War. They lost the armed conflict, but won Reconstruction, getting back their lifestyles with the slave labor replaced by peonage of the same people and poor whites.

Southern Man writes in: Of course, the Germans had another myth, this one truly believed by the leadership, that the Allies would set on each other. They did: it is called the Cold War. But not until the Germans were defeated.

Louis K writes: I think the Boer war would be an appropriate parallel.Having your land taken over by this imperial military machine, your families concentrated in camps, far away from the land that they love, your cattle confiscated, and being hunted around the Veld by para-military semi-professionals, and still having the will, and later the desperation to fight, looks to me very similar to the German position. And although the Boers probably had a little more of “a mission from god” feeling in them, it is a very human feeling to deny the fact that you might be wrong, or that all the hardship that you went through, and are still going through, was for nothing. And the fact that your government asks you to endure just a little bit longer, because hope for victory is just around the corner, which will vindicate your believe, and make the hardship worthwhile, will strengthen your resolve. Also knowing that you fight for a just cause, or at least a cause that you, and the population\army find just, helps you to go on. After all, some heavenly or other power will not let you fail in your mission. And honour, whether real, perceived, or misplaced, is also a powerful force to go on. Having sworn an oath on “Der Führer” for instance, and then breaking that oath, would dishonour you, and the side you fought for. ISIS could be argued to be in somewhat the same hopeless position now. They are surrounded by better armed and better trained armies, and their recruiting, and money\donations are way down. But they are on a mission from god, so they persevere. In 1918 the German High Command did come to the conclusion that it indeed was for nothing, just in time for the Allies to be denied acces to (hallowed) German soil. However, that decision was then twisted into the “Dolchstoss” legend, by people who were not aware of, or not interested in, the overall strategic and home-moral situation. And then they, and their wives, sons and daughters paid the terrible price for that 20 years later. In a way the Japanese had the same problem (of not recognizing defeat) but the Emperor, and several other high ranking diplomats, and officers, did make the decision to stop, again before the enemy would have touched (hallowed) Japanese soil. I am sure that the Germans were thinking the same in 1940, about why those pesky brits were still fighting. Their army was chased from the continent, their air force was being driven from the sky, and their navy was cowering in its harbours…. Why would they continu to fight the might of Germany? Just surrender, and be spared all the killing and hardship…. Republican Spain is also a case of fighting to the end, although that, apart from the “just cause”, might also have to do with the reception the losing party could expect when they wanted to surrender. Civil wars are almost never known for their adherence to conventions, Genevan or otherwise.

And if we look at resistance of non-military forces, all those underground movements were also deluded. Their armies were destroyed on the field of battle, and these civilians dared to oppose, and deny the inevitable? Unheard of, and criminal! Which brings me to the French in Algeria and Indochina, who were also in somewhat the same position, although the Vietmin was more on the way to battlefield victory than the FLN, but in both cases the homefront was no longer prepared to take the losses. The KwoMinTang, was also losing in a big way, but then sidestepped the issue by moving to Taiwan.Hope this helps.