Immortal Meals #29: Bourbon at Surrender May 25, 2016

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackback

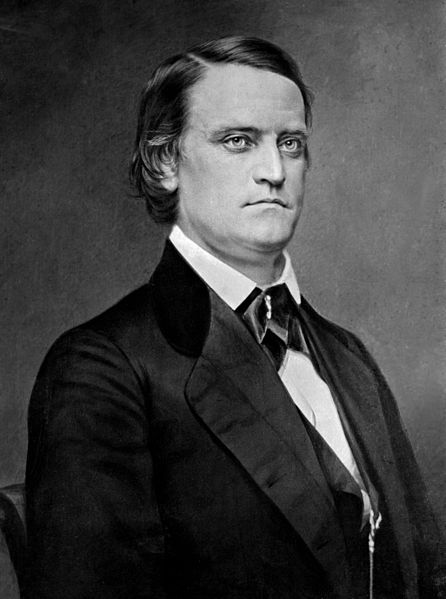

Surrenders are never very easy moments but the meeting between William Tecumseh Sherman and Joseph E. Johnston at Bennett Place on 17 and 18 April 1865 as the American Civil War was winding down proved a generally civilized affair. Sherman, the Union commander, was a Democrat and had a natural sympathy for the south: despite his burnings and killings on the march to the sea; Johnston, the Confederate, was, meanwhile, happy to find himself opposite a considerate victor and would later heap praises on Sherman, ultimately acting as a pallbearer at the Union commander’s funeral. Historians have often passed over their meetings as they were overshadowed by Lee signing his army over to Grant. But there is one episode that deserves to be better known and that is it involves a drink can go in the Immortal Meals series. The key figure in the story was ‘Major-General Breckinridge, who also happened to be the Confederate Secretary of War. The story was told by Johnson to John S. Wise.

‘You know how fond of his liquor Breckinridge was?’ added General Johnston, as he went on with his story. ‘Well, nearly everything to drink had been absorbed. For several days, Breckinridge had found it difficult, if not impossible, to procure liquor. He showed the effect of his enforced abstinence. He was rather dull and heavy that morning. Somebody in Danville had given him a plug of very fine chewing tobacco, and he chewed vigorously while we were awaiting Sherman’s coming. After a while, the latter arrived. He bustled in with a pair of saddlebags over his arm, and apologized for being late. He placed the saddlebags carefully upon a chair. Introductions followed, and for a while General Sherman made himself exceedingly agreeable. Finally, someone suggested that we had better take up the matter in hand. ‘Yes,’ said Sherman; ‘but, gentlemen, it occurred to me that perhaps you were not overstocked with liquor, and I procured some medical stores on my way over. Will you join me before we begin work?’ General Johnston said he watched the expression of Breckinridge at this announcement, and it was beatific. Tossing his quid into the fire, he rinsed his mouth, and when the bottle and the glass were passed to him, he poured out a tremendous drink, which he swallowed with great satisfaction. With an air of content, he stroked his mustache and took a fresh chew of tobacco. Then they settled down to business, and Breckinridge never shone more brilliantly than he did in the discussions which followed. He seemed to have at his tongue’s end every rule and maxim of international and constitutional law, and of the laws of war, — international wars, civil wars, and wars of rebellion. In fact, he was so resourceful, cogent, persuasive, learned, that, at one stage of the proceedings, General Sherman, when confronted by the authority, but not convinced by the eloquence or learning of Breckinridge, pushed back his chair and exclaimed : ‘See here, gentlemen, who is doing this surrendering anyhow? If this thing goes on, you’ll have me sending a letter of apology to Jeff Davis.’

However, the atmosphere would be shattered.

Afterward, when they were nearing the close of the conference, Sherman sat for some time absorbed in deep thought. Then he arose, went to the saddlebags, and fumbled for the bottle. Breckinridge saw the movement. Again he took his quid from his mouth and tossed it into the fireplace. His eye brightened, and he gave every evidence of intense interest in what Sherman seemed about to do. The latter, preoccupied, perhaps unconscious of his action, poured out some liquor, shoved the bottle back into the saddle-pocket, walked to the window, and stood there, looking out abstractedly, while he sipped his grog. From pleasant hope and expectation the expression on Breckinridge’s face changed successively to uncertainty, disgust, and deep depression. At last his hand sought the plug of tobacco, and, with an injured, sorrowful look, he cut off another chew. Upon this he ruminated during the remainder of the interview, taking little part in what was said. After silent reflections at the window, General Sherman bustled back, gathered up his papers, and said: ‘These terms are too generous, but I must hurry away before you make me sign a capitulation. I will submit them to the authorities at Washington, and let you hear how they are received.’ With that he bade the assembled officers adieu, took his saddlebags upon his arm, and went off as he had come.

What is most extraordinary though are Breckinridge’s words following on from the meeting.

General Johnston took occasion, as they left the house and were drawing on their gloves, to ask General Breckinridge how he had been impressed by Sherman. ‘Sherman is a bright man, and a man of great force,’ replied Breckinridge, speaking with deliberation, ‘but,’ raising his voice and with a look of great intensity, ‘General Johnston, General Sherman is a hog. Yes, sir, a hog. Did you see him take that drink by himself?’ General Johnston tried to assure General Breckinridge that General Sherman was a royal good fellow, but the most absent-minded man in the world. He told him that the failure to offer him a drink was the highest compliment that could have been paid to the masterly arguments with which he had pressed the Union commander to that state of abstraction. ‘Ah!’ protested the big Kentuckian, half sighing, half grieving, ‘no Kentucky gentleman would ever have taken away that bottle. He knew we needed it, and needed it badly.’

Some years later Wise shared the story with Sherman himself.

On one occasion, being intimate with General Sherman, I repeated it to him. Laughing heartily, he said: ‘I don’t remember it. But if Joe Johnston told it, it’s so. Those fellows hustled me so that day, I was sorry for the drink I did give them,’ and with that sally he broke out into fresh laughter.

Source: John S. Wise, The End of an Era (199) 450-451

Other immortal meals: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

30 May 2016, Nathaniel notes: Sherman should probably have cut back on the alcohol. His arrangements with Johnston and Breckinridge got him into trouble with his superiors, who felt that he’d greatly overstepped his authority as a general to make what were actually political decisions. These included recognition of existing Southern state governments. As an official put it at the time “[generals] in the field must not take it upon themselves to decide on political and civil questions which belonged to the Executive”. Grant was directed to notify Sherman that his (Sherman’s) actions were disapproved.

30 May 2016, Bruce T. I’ve got relatives in Danville, VA. “Hog” is still an insult there. It goes from “Hog” to “Damned hog” to “Damn sweat hog.” with variations on each. “Butt-ignorant” or “Butt-Ugly” are often thrown in for effect in appropriate spots for effect. Appalachian cussing is an art form, improvisation and style count.