Perhaps in My Father’s Time… July 27, 2016

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackback

Beach and his loved ones are having a difficult time. A friend on holiday has shattered his heel and is now in hospital awaiting an operation. He doesn’t speak Italian and so Beach has been drafted into sitting in the hospital ward to make everything run smoothly. Beach hates hospitals. At least, though, he can read a bit… While in the ward yesterday Beach turned up this description from a book of northern English history. It is a lazy post, in days when Beach has little time and almost no access to computers. But he found this passage incredibly moving. It links into a long-standing interest of this blog. How we and how communities remember the past. A Cumbrian historian Molly Leferbure is talking to an elderly informant in the 1970s: he had been born in the 1880s.

The late Mr George Bowe, who was in his nineties at the time, was kindly discoursing to me upon local lore in general and his lengthy family tree and ancient statesman lineage in particular when, suddenly, he stopped short in his conversation and turned to me with a face of distress. ‘Have you heard about the terrible disaster up at the mine?’

‘Which mine is that?’ I asked, alarmed.

‘Why, Stoneycroft mine, up yonder.’ He nodded in the direction of Barrowside and Stoneycroft Gill. ‘The early morning shift all lost; not one man saved!’

‘How dreadful!’

‘The main working yonder is in the gill bed; the shaft is in the bed of the beck itself, like. They built a dam upstream so that the water flowed aside, through a channel cut in the rock.’

‘Yes, I’ve seen it.’

‘Well, the lads had just gone down the mine on the early morning shift when the dam burst. The water poured back into its old course and down the shaft; every poor lad below ground was drowned. Every one. Nothing could be done to save ’em.’ He paused, his agitation great. He repeated, ‘Every one drowned. Not a thing could be done to save ’em.’

His sister, almost as old as he, echoed his words, ‘All drowned. All drowned.’

They stared at me with the faces of those who have lived in community which has known tragedy. Mr Bowe continued, ‘They couldn’t reach the bodies. Never so much as got one body out. Aye, it was a bad business. A black day for Newlands.’

There was a melancholy silence in the little parlour. Miss Bowe, sighing, mournfully poked the fire in the range. Mr Bowe repeated yet again, ‘Aye, every poor lad drowned’.

I had read about this disaster in Postlethwaite, who gave it no date. His account was a scant, dry, three or four-line reference, in no way comparable with Mr Bowe’s, which bore all the stamp of the first-hand. Intrigued, I asked my host, ‘You don’t remember this disaster, do you, Mr Bowe?’

‘Nay, nay; well before my time. It was our father told us about it.’

‘He often spoke about it,’ said Miss Bowe. ‘A dreadful day in Newlands.’

‘Was it in your father’s time?’

Mr Bowe reflected. ‘That I couldn’t say for certain. I think it was but I couldn’t say for certain. It might have been in his father’s time and he handed it down, like, but whenever it was that it happened, my father knew about I well. How the morning shift went down and then, almost directly after, the dam broke. It had been raining all night and there was a lot of water coming down at the time.’… Mr Bowe was quite unable to assist with suggestions for a possible date: father’s time, grandfather’s time, a remote possibility that it might even have been in his great-grandfather’s time.

Can anyone date this accident: drbeachcombing At yahoo DOT com

Molly Lefebure, Cumberland Heritage (London 1970), 24-5

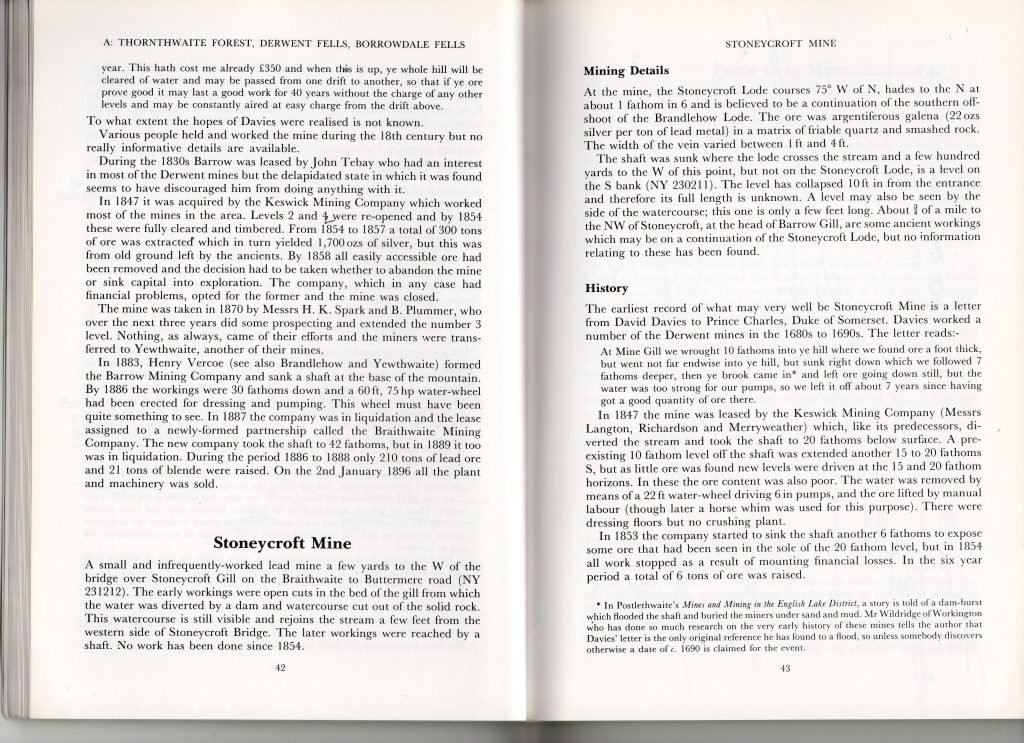

Mike S writes, 31 Jul 2016: As an inhabitant of Bury, Lancashire and having read your periodic references to this part of the world I had a feeling that sooner or later I would be able to make a contribution. So, having read the post about the Stoneycroft Mine accident I decided to consult the excellent (if not a little obscure) ‘ Mines of the Lake District Fells’ by John Adams which has been in my possession for some considerable time waiting for just such an opportunity. It transpires that the only reference found to the Stoneycroft mine flood is a letter sent from a certain Mr David Davies to Prince Charles, Duke of Somerset. The date … sometime around 1690 (see scan of relevant pages attached under History and in the note at the bottom of the page). As in many of these stories that are handed down, the date is seldom as important to those recounting the tale as the events and thus eventually gets lost over time. Incidentally there are many good tales surrounding the mines of the Lake District, not least of them the ones about the ‘Black Wad’ (Graphite) mine of Borrowdale whose produce was so valuable as a moulding agent used in the manufacture of Cannon Balls that an Act of Parliament was passed in 1752 that made illegal entry to or stealing from the mine a felony punishable by a public whipping plus either 1 years hard labour or seven years transportation!

Stephen D, 31 Jul 2016, writes: The date you are looking for may be around 1680. To quote Mai Tabb (http://maltabb.blogspot.co.uk/2015/07/stoneycroft-ghyll-present-past.html): “The ghyll was first mined in what I would refer to as its lower reaches, near to the bridge, for lead by the early German miners. Around 1680 the engineer David Davies sank an engine shaft in the stream bed, however, the elements prevailed and heavy rains burst the dams he created tragically drowning the miners downstream. Mining did not re-commence until the mid-1800’s; a 22′ water wheel was constructed amidst extensive engineering. The project did not last and mining ceased again after less than ten years. There is more on this in the excellent: “The Lakes & Cumbria Mines Guide” by Ian Tyler.” I’ve no access to Tyler’s book. It’s still in print, if you want to chase it up. £30. Christopher Mitchell, in “Lake District Natural History Walks”, p23, gives 1690 as the date of the disaster, and adds “The mine was reopened in 1846 but the bodies were never found“. My italics. Much virtue in your “but”. Anyway, that makes the disaster a good two centuries before the late Mr George Bowe first heard of it: call it 6 to 8 generations. But of course, his father or grandfather may have heard of it from the miners of 1846, reopening the mine and searching in vain for bodies; and they may have known of it from written mining records.

Lisa, 31 Jul 2016 also got 1680 and comments: Your post reminds me of something in my own family memory. When my great-grandmother was a little girl on a farm in Latvia, one of their cats somehow accidentally hanged himself in their barn. My g-g was the one who found the body, and the sight was something that always stayed with her. When my grandmother was a girl, my g-g told her about the cat. My grandma never forgot that, either, and she eventually related the incident to her daughters, and then me. I’ve always been touched by it as well, but as I’m childless, I suppose the memory will die out with me. I have always found it remarkable how this unfortunate cat’s little anonymous tragedy has lived on through all those generations. You could say this kitty has never really died.