History Branching June 23, 2017

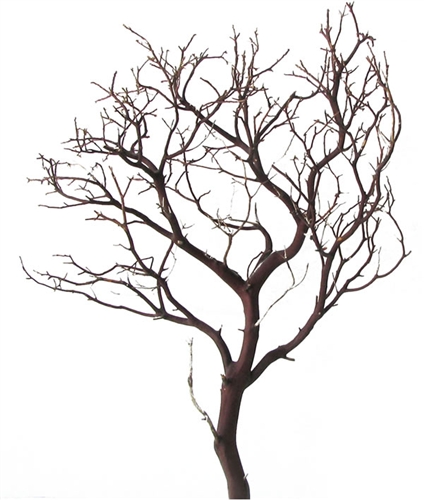

Author: Beach Combing | in : Actualite , trackbackToday is the anniversary of Britain’s vote, suicidal or brave as you see fit, to leave the European Union. Beach thought he would remember that day with a quotation that has more resonance with him than anything else he has read on the campaign because it describes a strange lived historical experience: the sense of different historical possibilities co-existing. This is Dominic Cummings on ‘branching histories’ the way that there are always different possibilities out there.

You see these dynamics all the time in historical accounts. History tends to present the 1866 war between Prussia and Austria as almost inevitable but historians spend much less time on why Bismarck pulled back from war in 1865 and how he might have done the same in 1866 (actually he prepared the ground so he could do this and he kept the option open until the last minute). The same is true about 1870. When some generals tried to bounce him into a quick preventive war against Russia in the late 1880s he squashed them flat warning against tying the probability of a Great Power war to ‘the passions of sheep stealers’ in the Balkans (a lesson even more important today than then). If he had wanted a war, students would now be writing essays on why the Russo-German War of 1888 was ‘inevitable’. Many portray the war that broke out in August 1914 as ‘inevitable’ but many decisions in the preceding month could have derailed it, just as decisions derailed general war in previous Balkan crises. Few realise how lucky we were to avoid nuclear war during the Cuban Missile crisis… and other terrifying near-miss nuclear wars. The whole 20th Century history of two world wars and a nuclear Cold War might have been avoided if one of the assassination attempts on Bismarck had succeeded. If Cohen-Blind’s aim had been very slightly different in May 1866 when he fired five bullets at Bismarck, then the German states would certainly have evolved in a different way and it is quite plausible that there would have been no unified German army with its fearsome General Staff, no World War I, no Lenin and Hitler, and so on. The branching histories are forgotten and the actual branch taken, often because of some relatively trivial event casting a huge shadow (perhaps as small as a half-second delay by Cohen-Blind), seems overwhelmingly probable. This ought to, but does not, make us apply extreme intelligent focus to those areas that can go catastrophically wrong, like accidental nuclear war, to try to narrow the range of possible histories but instead most people in politics spend almost all their time on trivia.

Later in the essay he rounds off this thought with specific reference to the referendum:

Anybody who says ‘I always knew X would win’ is fooling themselves. What actually happened was one of many branching histories and in many other branches of this network – branches that almost happened and still seem almost real to me – we lost.

The Brexit Referendum was, without any question, the strongest political experience of this blogger’s life and in the weeks immediately afterwards he often found himself living in two worlds: one in which Britain voted to leave the EU (as she did), and one in which the country voted to remain. The two possibilities were both so credible, and the result had been so close, that those other ‘branches’ had a dreamy post coital existence; they floated around the room in the evening with pipe smoke and the mosquitoes. The sensation fell off in the months following on from the vote; and now, a year on, the idea of two different existences seems absurd, quite simply because so much has happened. Is this normal when you live a great change, perhaps particularly one that is presaged, but where the reality takes some time to kick in: a nation voting for a change in a year’s time is very different from a nation having a nuclear bomb dropped on it? drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com Not sure.

30 Jun 2017: Chris S writes as an answer to this: ‘Is this normal when you live a great change, perhaps particularly one that is presaged, but where the reality takes some time to kick in: a nation voting for a change in a year’s time is very different from a nation having a nuclear bomb dropped on it?’ It’s because we’re still alive. Now there’s a different pistol being held to western civilization’s temple. Growing up in the 1980s, I had nuclear war pointed at my temple for years. Suffused my nightmares. At least with nuclear war, you know you’re going to die. With the rise of nationalism and fascism, you don’t know if you’re going to be next or the brown fellow next door.