Best Ghost Story: Paris Station Ghost October 8, 2017

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackbackThis is one of the very best ghost stories: partly because of how its written; partly because of how difficult it is to explain away. The author is Shane Leslie, an Irish member of the British establishment in the 1920s and 1930s, a cousin of Churchill and a witty and delightfully gossipy talker. He had a lifetime interest in the supernatural particularly the undead: he had been a student of M. R. James. ‘This was an experience which I can describe an experience which I reckon the most vivid of my life. It is a ghost story, but with dates, facts, places and even a few surviving witnesses to my tale. Even so there is no explanation.’

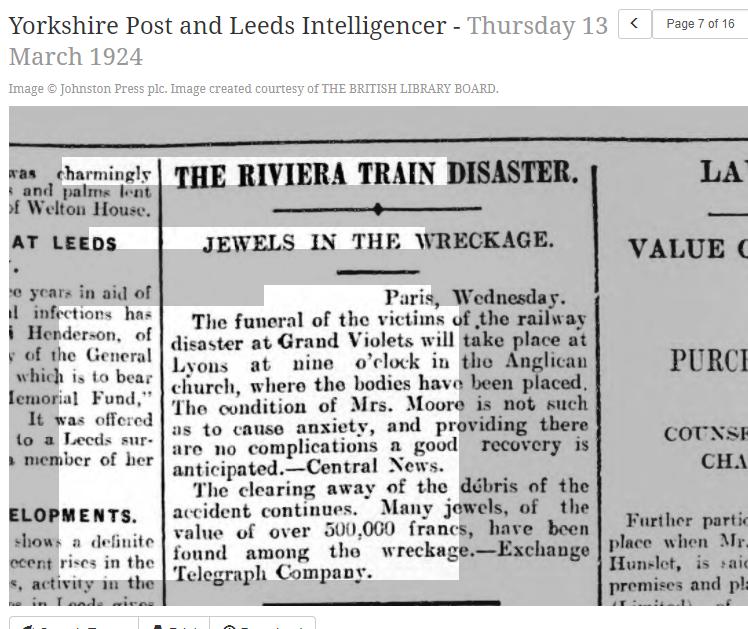

Here we go. The image at the head of the post will soon make sense.

It was in March, 1924, when I was working in London and received word that my wife was not well at Cannes on the Riviera, and that I should come out as soon as I could. It was a week-end when I arrived in Paris. It was Sunday, March 9, that I proposed to take the ‘Rapide’ or express train south. I brought no luggage save a bag, and carried my dressing-gown over my arm. I was in a great hurry and telegraphed to a friend in Paris, who survives to recall the incident. He gave me a lunch and we spent the afternoon motoring. The ‘Rapide’ was due to start at 8.10 that evening, and my friend left me at the great station of the Paris, Lyons and Mediterranean route about an hour before the train started. He was an American priest and is now a Canon in Rome.

I had not engaged a seat and it was too late to take a sleeper. I represented my case and how necessary it was for me to travel by that train. Whether I paid extra or not, I was accommodated with a seat in the restaurant, and there I laid my humble belongings. With an hour or so to kill I decided to stretch my legs by walking up and down the platform so well known to the thousands who travel south every year to the Riviera. I began walking up and down past those endless iron pillars. Half-way down I turned and retraced my steps. The next ten minutes are unaccountable in time. At the spot where I turned on each lap of my walk I became aware that the figure of a woman was standing and looking in my direction. I could describe her as an Italian-looking lady wearing deep mourning. Of one thing I felt certain. She wore a black hood over her head. Every time that I completed walking the length of the platform she was waiting for me, and her eyes were turned full upon me until I became quite expectant of their piercing brilliances.

How can I describe them? They were anything but the glad eye. They were sad and luminous. Their effect was not so much fascinating as hypnotic. I think that is the only description I can give of them after several years, thirteen years actually, since they had such a curious and decisive effect upon me. After I had passed her for the third or fourth time my feelings were not as agreeable as might be the case with a susceptible traveller; but decidedly uncomfortable.

Looking back after the years with my full ordinary senses, I do not believe now that such a person as I have described was ever standing there visible to the eyes of all who passed, but that I was being subjected to a remarkable hallucination. For reasons I cannot understand and under rules that I do not know, her visual appearance was admitted to my sense of sight and at the same time I became conscious or subconscious that she was telling me in French that I must change my train. The words that formulated in my mind were, il faut changer de train. And they were repeated. I was in a mental condition which admitted no argument or reasoning with myself. I was in a mood partly nervous and partly adventurous. I felt no apprehensions. But I felt that something very novel and intensely personal had glided into my life of which an hour before I had not the least knowledge. I was tired and I had had a certain amount of brain-fag before I left London. Now I had a feeling that I no longer controlled and even commanded. I turned round and I obeyed. I took my belongings out of the ‘Rapide’ and after a short inquiry I took my seat in a slower train which was leaving later for Marseilles from the next platform. I looked round, but I never caught sight of my strange guide again. I walked down the platform but she had utterly disappeared.

As I say, I do not believe that she was ever visible or audible to anyone who was not at the time in a receptive state of mind or imagination. I suppose I imagined it all but I cannot regret that I did. The slow train was very crowded and I settled myself down with five others in a single compartment and prepared myself for an uncomfortable night sitting up. Horns and whilstles blew to announce the departure of the ‘Rapide’, and I became aware that the train in which I had first taken a seat was slowly moving out of the station. I leaped out and watched. It was then that I first experienced a feeling, a dreamy but very vivid feeling, that I was fey. That is the only word which the language supplies to describe a state of waking dream which be so much more vivid than the processes of ordinary humdrum life. I watched in a fascinated way the train as, slowly and noiselessly, it stole away. Then again I had the feeling that time was standing still or at least that I was standing still or at least that I was standing aside from time. It was eight o’clock in the evening and the departing train was brilliantly lit, but it crossed my eyesight more brightly than any train I had ever seen. My vision was like that of a man suffering from short sight who has suddenly been furnished with excellent glasses. He almost feels that he has received a new sense. Life instantly furnishes a brighter blue, a more radiant red, while blurred lines become almost mathematical.

I watched the train. It might have been for ten seconds, but it might have been for an hour. It was so timeless. Every carriage that passed was imprinted upon my mind and memory, and for days afterwards I could recall every person I glimpsed. Two remain with me to this day: the Chef with his cap who looked almost transfigured in his white array against the night: and a face that peered for a moment on the platform and then disappeared behind a drawn blind. Others were settling down for the night and then, as when a brilliant dream comes to an end, the whole panorama suddenly ceased and I turned back into my dingy train wondering whether I could be such a fool as I thought I was.

I slept and half-slept all night, and was heartily glad when we reached Marseilles. Thence it was brief journey to Cannes, which I did not reach till two the next day. I did not feel very enthusiastic when I found myself at my destination. I had not destination. I had not telegraphed the exact hour of my coming, and this was fortunate. In any case there was nobody to meet me and I made my way to the hotel where I was expected.

Here I was joined by a Canadian friend with a car who offered to take me for a drive. Casually she mentioned that I was lucky not to have been on the ‘Rapide’ that night. I felt overwhelmed. ‘But I was,’ I said. ‘Oh no, that was impossible or you would not be here. The ‘Rapide’ met disaster some hours after leaving Paris. There have been a dozen casualties and some well-known people from England are reported to be killed.’

This gave me a considerable shock and I hurried round to make inquiries. It was no use saying I had been on the train for while, and no one believed me. During the experience in Paris I had never as much as dreamed of an accident. It had not occurred to my mind that there was any danger. I had obeyed an impulsion that I could not resist, but which did not seem connected with any sinister import. I learnt to my regret that among the casualties had been an old Eton acquaintance, De Falbe. It was some time before I realized that I had only just missed being in a railway accident. My next feeling was one of relief that I had missed such an excitement, but on reflection I realized that I had passed through a much more exciting one on another plane.

The story appears in Leslie, The Film of Memory (1938), 411-415: though allegedly the exactly same text had appeared in the Listener in 1937: non vidi. It was presumably a radio talk. For a rationalist like Beach there is hay to be made here. The woman on the platform presumably really existed: Leslie was in a strange frame of mind. The extraordinary impressions of the train might have become very striking in memory, watching a train rush out is a wonderful thing: and retrospectively became marvellous. (There is an outstanding poem – by Simon Armitage? – about the experience that frustratingly Beach can’t find. A girlfriend rushes down to the opposite platform and is caught by another train like a threaded film.) The one fact, though, the one thing that cannot be talked away (always assuming we trust Leslie’s honesty) is that he changed trains. That is more difficult to handle. Here is his coda to the tale: message from the other side. Now it doesn’t all make sense.

When I returned to Paris I gave an account of what had happened to me to a group of people interested in spiritualism. I was told that the accident had been the cause of several incidents in the spirit world, of which mine was but one. It was explained to me as the attempt of somebody beyond the veil trying to get into touch with some friend in the train who had not been responsive to the message. In my state of mind I must have received it and interpreted it to myself. Be that as it may, the facts remained that I had been taken to catch one train and had arrived on another. To me it remains as inexplicable as the wireless would be to my grandfathers.

Great ‘true’ ghost tales: others, drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com