If I Were Your Husband I Would Drink It: History of a Joke March 20, 2018

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackbackThat Joke

The words are famous and supposedly came out in a verbal duel between Lady Astor (Britain’s first active woman MP) and, from a different wing of the Conservative party, Winston Churchill.

Lady Astor: ‘If I were your wife I would put poison in your coffee.’

Churchill: ‘Nancy, if I were your husband I would drink it.’

It is one of several spats that these two are said to have had and regular readers will not be surprised that the conversation is absolutely undocumented. The joke is first found in print in 1899 (sans Churchill); and first associated with Churchill in 1949, and, then, first associated with Churchill and Astor in 1952.

From the US

All this has been established by an excellent page which has tracked this exchange back to 1899 and the US press. I’m intrigued above all, by the way that the joke evolved afterwards in Britain. I’ve spent a lot of time in the last few years following urban legends, but this is the first time I’ve tracked a simple apocryphal exchange. The first thing to say is that the story crosses the Atlantic in the by early 1900; and the first references notes its American origin.

A fierce battle was raging in a railway carriage between a male and a female. He was smoking where smoking was strictly prohibited. She objected, on principle and because she loathed the ‘beastly weed’. There was no lack of ammunition, and the attack threatened to last through the whole journey, till the woman ever hoping to have the last word, shrieked: ‘If you were my husband I would put poison in your coffee.’ ‘And’, replied the man, ‘if you were my wife I would gladly drink it.’ With this cruel and victorious shot he left the carriage, feeling he had won the day. (Graves 6 Jan 1900, 7)

Compare this, though to the American original: it looks very much as if a British newspaper was not prepared to go with a drunk and chose something much more familiar to home audiences, arguments over smoking on public transport. Subsequent US versions went with alcohol and dropped tobacco.

The “Listener” reports the following from the subway: On one of the recent warm days a sour-visaged, fussy lady got on one of the smoking seats on an open car in the subway. Next her sat a man who was smoking a cigar. More than that, the lady, sniffing, easily made out that the man had been eating onions. Still more than that, she had the strongest kind of suspicion that he had been drinking beer. The lady fussed and wriggled, and grew angrier, and looked at the man scornfully. Presently she could endure it no longer. She looked squarely at him and said: ‘If you were my husband, sir, I’d give you a dose of poison!’ The man looked at her. ‘If I were your husband,’ said he, ‘I’d take it!’

I have only found one ‘drunk’ version of the joke form the UK and that dates to 1940, Tatler (7 Aug 1940), 28. Onions, sadly, never figure…

Heckling

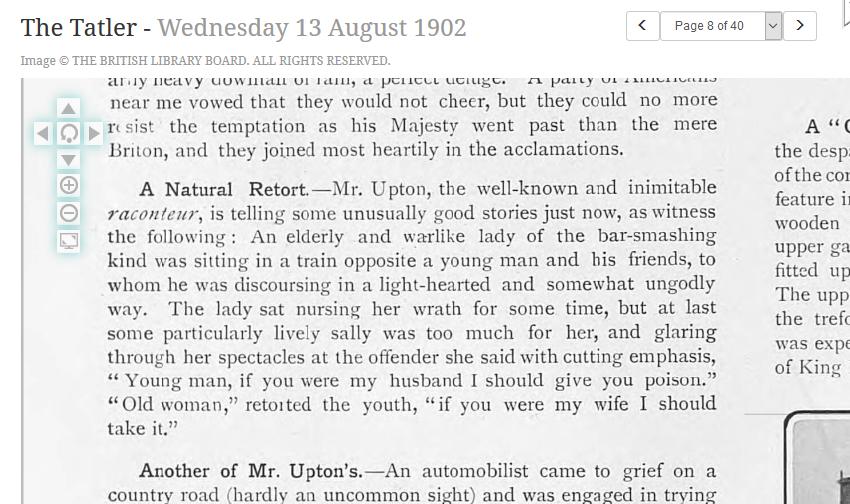

The joke remained with nicotine for many years and was quickly naturalized to the UK. In fact, already by 7 Mar 1900, the Portsmouth Evening News set the tale on ‘the District Line’! By August 1902 ‘Mr Upton Sinclair’ is boasting of it as one of his own creations.

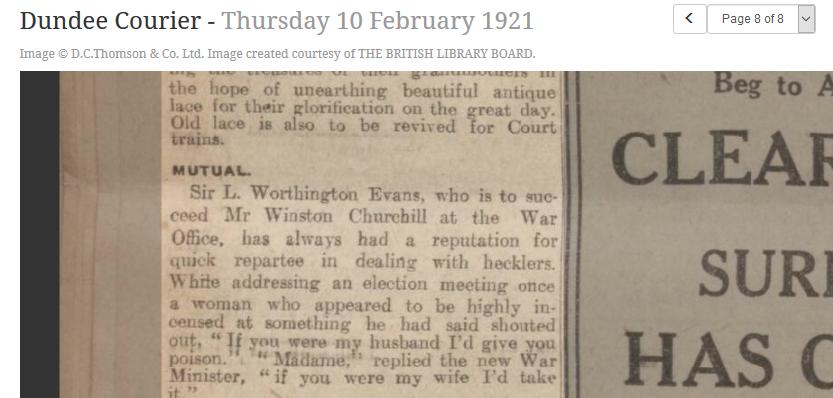

By 1907 it was set in a London hotel: Tatler, 4 Sep 1907, 24. (Yes, the joke was told three times in the same magazine!) However, the next bound in its evolution came when it was introduced as an electioneering story: the witty candidate puts down a heckler. The first of these I’ve found from the UK dates to 1916, though it was set sometime in the previous decade. Ida Poore in her Recollections of an Admiral’s Wife is recalling Sir George Reid taking on opponents in his meetings. (‘When a woman in the audience cried out, ‘If you were my husband I’d give you poison! ‘Sir George remarked, ‘Madam, if you were my wife I’d take it.’) The story was told of Sir L. Worthington Evans in 1921 (see below). Note the first very distant association with Churchill.

It is also told, in 1921, for a by election in Wales where a heckler sets off the run of words. A woman shouts: ‘If I were your wife I would put poison in your tea.’ Mr Llewelyn Williams (promptly): ‘And if I were your husband I would drink it.’ (‘A Candidate’s Retort’, YEP (24 Feb 1921), 6). In 1925 in a refreshing gender reversal a suffragette (Annie Kenney) remembers it being used against an obnoxious elderly man who kept heckling in Somerset (oh England…). ‘Yes and were I your wife I’d take it!’ In 1935 the story is told of the MP for Argyllshire F. A. Macquisten while he campaigned (Der D Tel, 30 Nov 1935, 5). By 1940 the Bath Chronicle offers the tale for an anonymous professor at a meeting (30 Mar, 9). Note that in the US there are only two reported instances of political meeting, one involving a British politician. It seems that this version of the joke was a British innovation, then.

Two Known Actors?

We have seen so far duels between strangers in a public (rail carriage and hotel) and a very public (meeting) setting. Where does the duel between two known parties begin? I’ve found one Canadian example from April 1918. In the senate, no less, the speaker A Boyer gave this version: ‘But to come back to my old friend who stood in front of this lady and disapproved of everything she said. At last, as a final argument, she asked him. ‘You don’t believe in votes for women?’ He said, ‘No’. Then she looked at him as cross as possible and said: ‘Sir, if I were your wife I would poison your tea.’ And what do you think the gallant old gentleman did? With a smile he said, ‘Madam if I were your husband I would drink it’ Debates Senate 1918, 362. A much earlier English version (1906) involves that standby of so many British jokes, the mother in law. ‘If I were your wife’ said the irate mother-in-law, ‘I’d give you poison.’ ‘If you were my wife’, replied the son-in-law meekly, ‘I wouldn’t wait for you to give it me. I’d take it on my own accord’ (Nor D Tel, 1 Nov, 8). Perhaps Churchill and Lady Astor were, in 1952, the first version to use two publicly known figures?

Challenge

Can anyone get earlier than 1899: drbeachcombing AT gmail DOT com. Or drag known actors back before 1952?