Helen Duncan and HMS Barham: A Sceptic Speaks March 22, 2018

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackbackIntroduction

It is one of the most extraordinary psychic events of the twentieth century, rave some. It proves that mediums really can communicate with the dead, state others. A Scottish medium, Helen Duncan brought, in early December 1941, a relative of a crew member of HMS Barham into contact with her recently dead son (or according to other accounts a husband). Of course, meeting the dead is always comment-worthy, but this is a particularly curious episode because it was not, when Duncan gave her séance, officially known that HMS Barham had been sunk. How could Duncan have found out? Is this the proof from the other side that some have long been waiting for? Or are there other more mundane explanations?

Helen Duncan

Before getting to the crucial chronology a little background on the two protagonists: Helen Duncan and HMS Barham. Duncan (1897-1956) was from Perthshire and was, by the 1940s, one of Britain’s most famous mediums, her contact being a garrulous, bitchy spirit named ‘Albert’. She was fixed in the public imagination in 1944 when she was prosecuted under the 1735 Witchcraft Act and sent to prison for nine months. There were provisions in said act against fortune telling, and it also made for excellent wartime press copy ‘Witchcraft’ etc.

Duncan was particularly famous as a medium for materializations, which should set alarm bells ringing. Indeed, on several occasions she was ‘caught’ in the act of faking aspects of contact with the other side. In the world war she also found herself advising, with these dubious methods, family members who wanted to know whether a loved one was alive or dead. There is a vocal minority that consider Duncan to have been a genuine talent. She may have been, as many mediums, well meaning, but this photograph should dispel the idea that her act was always everything it claimed to be.

Duncan worked as a medium in various parts of the country in the early 1940s, and from December 1941 there are newspaper notices of her working in the Portsmouth area, where she frequently stayed. ‘Helen had been visiting Portsmouth from the start of the war, if not even earlier, but by the end of 1943 she had become a regular at the Master Temple, boarding for days on end with a Mrs Bettison in Milton Road’ (Gaskill, 178).

Crucially, many of the crew of Barham came from the Portsmouth area.

HMS Barham

HMS Barham (1914-1941) was, at the beginning of the Second World War, among the largest warships in the world. But by WW2 size no longer mattered. In fact, submarines and planes meant that warships has become a dangerous anachronism in a conflict where radar and aircraft carriers would decide the day. Barham served in the Mediterranean under the incomparable Admiral Cunningham and would do some good work there, taking part, for example, in the last ‘old style’ fleet action in history, the Battle of Matapan, and knocking out two Italian ships on that occasion: a destroyer and a cruiser.

However, Barham’s luck was running out. 25 November 1941 a German submarine wove through a destroyer screen – it is difficult not to admire the pluck of the German captain* – and sent four torpedoes into Barham. The ship began immediately to list. Most of the crew should have been saved. Unfortunately, though the magazines exploded killing 862 British sailors, with some 400 surviving. There is clip showing the destruction of the Barham, filmed from HMS Valiant. Be warned: it is a chilling viewing experience.

Chronology

So did Duncan bring news of the Barham’s sinking before it was publicly known? Well, the first thing to establish is chronology.

25 Nov 1941 (not 24 Nov as stated in many places) HMS Barham was sunk near Malta. However, this information is immediately classified, not least because the Germans seem not have been sure that the Barham had gone down.

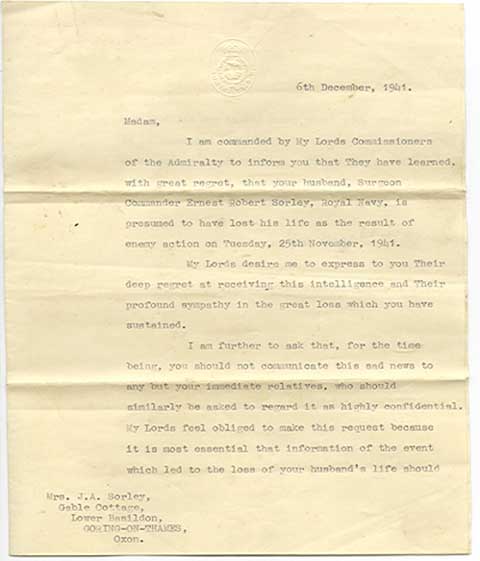

6 Dec 1941 The Admiralty sent out letters to relatives who were told of the destruction of the ship some weeks before the official announcement. They were asked to tell no one save close relatives for reasons of national security. (Imagine walking around with that information in your pocket).

27 Jan 1942 The British press was finally allowed to admit that Barham had been sunk.

Nov 1942 The Portsmouth press runs many in memoriams for those who died a year after the sinking. (I choked up when I read ‘still hoping’ in the screen shot below). This is a just a small cut from a horribly large acre. Barham clearly had many crew in the area.

March 1944 Helen Duncan court case

The Date of the Séance

The million dollar question is when Duncan made her predictions. If she conjured up a ghost from Barham on say 25 November then that really was an achievement. If, instead, it was mid January when the families of Barham knew, then that was a good deal less remarkable: we are talking of hundreds just conceivably thousands of people being ‘in the know’ in the Portsmouth area alone. Duncan also came into contact with bereaved people on a regular basis, adding to the odds that she would have heard. In between, those two dates the chance of information leaking out grew. It is also worth remembering that there had been about four hundred survivors from Barham and that thousands of other British and Dominion sailors had seen Barham go down: she had been at the heart of a Mediterranean convoy when the torpedoes had struck.

Our only real clue for a date for the séance comes 26 Dec 1941 when Guy Liddell, the wartime head of British counter intelligence, recorded the following in his diary.

The Barham case has come up once more [i.e. the need to keep it secret]. A medium has produced a drowned sailor called Syd who was recognised by several people present at the séance and said he was one of the crew. Edward Hinchley-Cooke and Edward Cussen are once more taking up the trail.

The medium is almost certainly Helen Duncan. Liddell was clearly worried that information had leaked into the public sphere. But again the problem is nailing down when the séance took place. Sometime, necessarily, between 25 Nov and, say, 24 Dec. Remember that any time after 8 Dec families (including many in the Portsmouth area), knew of the Barham’s loss (I’m adding two days for the news to arrive by post).

The Séance

What actually happened at this séance? The canonical description was given by Percy Wilson in 1958 in his defence of Duncan.

The story so far as I am concerned began with an invitation to me to have lunch with Maurice Barbanell. During that lunch he asked me if I had heard what had happened at a Helen Duncan seance at Portsmouth the previous evening. He told me that he had had a message that morning to say that at this seance a figure had appeared of a sailor with a capband H.M.S. Barham; and the information was given that the Barham had been sunk in the Mediterranean but that the fact was not to be announced for three months because of the political and military situation. I went back to my office. I was then what you might call a senior official of the ministry of War Transport. I was in a detached building, Devonshire House, whereas the main office was in Berkeley Square House; so I deliberately went along to Berkeley Square House to ask some of my senior colleagues and remember, the Ministry of Shipping was part of the Ministry of War Transport whether they had heard of the sinking of the Barham in the Mediterranean. No one had heard, but one of them said he would make an enquiry; and he told me later that afternoon that it was not known in the Ministry of War Transport. That was on the day after the message had been given in Portsmouth. Well you will find, as I found, that in fact the news of the sinking of the Barham was only released three months later and the explanation was given that it was not in the public interest to reveal the fact at the time. You can imagine the consternation and feeling in Portsmouth when this piece of rather colourful information had appeared at a seance with Helen Duncan. In passing I would have you observe that although this was a physical seance, it contained evidence at the same time, rather straight evidence, of the survival of the particular boy who came back to speak to his mother.

Duncan had form in using hats (Mirror 24 Mar, 2), so the possibility that she produced a spirit ‘with a capband H.M.S. Barham’ is a real one: note, though, that in war British sailors just wore ‘HMS’ on their caps for security reasons!

Simon Edmunds claims, instead:

In fact the sitter concerned was the widow, not the mother, of a petty officer who was lost in Barham, and Mrs Duncan did not give the name of the ship, but extracted it from the sitter.

I’ve not been able to establish his source for this information: it would be important to do so.

How Did She Do It?

I assume that the séance took place in mid December. I assume that in Portsmouth the death notices had sent out ripples into the community. A grieving mother may know that she should not tell the gossipy next door neighbour that her son has just been killed, but this is a grieving mother… Let’s say that a hundred of the Barham’s dead crew were from the Porstmouth area and that each family meant five individuals in the area knowing: that is five hundred individuals walking around in a small city with information so secret that the British government did not even include it in its own executive intelligence briefings.

A key passage in the Wilson’s story is the rather strange claim that ‘the information was given [through the ghost] that the Barham had been sunk in the Mediterranean but that the fact was not to be announced for three months because of the political and military situation.’ I have real problems believing that a disembodied voice said ‘But Mum the government has said that you mustn’t tell anyone for three months’. This sounds like Wilson unconsciously making the psychic feat more impressive a decade later: the British government only decided to release the information when it was clear Germany knew about Barham.

However, I can imagine a voice saying ‘I’m dead and the government wants this kept quiet for the sake of the war’. If that was said then there is an excellent chance that Helen Duncan’s source was one of the letters sent on 6 Dec that made just this point: perhaps an earlier client had brought a letter along when requesting comfort. It might be worth adding that HD’s own son Peter was serving on HMS Formidable as a signalman: Helen likely found it particularly easy to enter into the mind of a grieving navy mother or wife because she must have lived constantly with that imaginative burden. Duncan’s Barham séance was an act of social cold reading: she’d got the information, I would guess, not from the woman before her but from the city where she was temporarily living.

Other Things

In writing this I failed in a couple of points that I throw open to others: drbeachcombing AT gmail DOT com I’d also be fascinated at any comments on the points offered above.

First, Maurice Barbanell wrote his The Case of Helen Duncan in 1945 and defended Duncan in this pamphlet: I have not been able to consult this rare work and it would be fundamental to copy out the passage on the Barham there. Can anyone help?

Second, I know that Helen Duncan was supposed to have predicted the sinking of the Hood: I’m doing that one tomorrow. In some respects it is more challenging for a sceptic: I’ll link it when it is up. Link here.

Third and finally, there is the allegation that the British government went after Duncan because it was feared that she would reveal other state secrets in her séances. If this was the case then I find it incredible that they waited till 1944 to try her! I suspect that this is just wishful thinking on the part of spiritualists and Helen’s other supporters. I personally find it distasteful that the powers that be sent Duncan to court and it is awful to report that she was, afterwards, sent to prison. Duncan seems to have been a fundamentally good person who brought comfort to many people; she was not greedy and those who came to her seem to have wanted to see things that weren’t there. She provided that service. The idea, though, that she was a spiritualist Mata Hari and that the government was trembling does not convince!

Sources

I started with Malcolm Gaskill, Hellish Nell and then went back to original sources like the Wilson talk from 1958: my conclusions differ from MG’s in a couple of respects, though his book is a wonderful read. As noted above I’ve failed to find Barbanell’s The Case of Helen Duncan or Edmund’s source; using Google Books snippets there… I also want to recommend in the highest possible terms the HMS Barham’s site.

*The single weirdest fact that I came across while researching this was that the German captain of the u-boat actually went to an HMS Barham reunion! I’d love to learn more about how that worked out…

Tacitus from Detritus of Empire writes in, 29 Mar 2018: On all matters pertaining to u boats the go to source is uboat.net. The u boat captain in question, a chap named Tiesenhausen, became a POW when his damaged and sinking boat was strafed by RAF planes while he was flying a white flag attempting to surrender. Maybe the RN chaps at the reunion knew this.