Ann Jefferies and the Fairies: A Cornish Fairy Witch November 29, 2021

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackbackThe subject of this month’s podcast is Ann Jefferies (1625-1713), a Cornish fairy witch. An accompanying Pwca book is available on Amazon: Ann Jefferies and the Fairies A Source Book for a Seventeenth-Century Cornish Fairy Witch

Introduction: Ann and the Fairy Witches

Ann Jefferies (aka Anne Jefferies, Ann Jeffries etc) started seeing fairies in 1645. She was 19. The fairies were about the size of children of three or four years of age and they wore green. They always appeared in even numbers and there were male and female fairies. Ann was neither the first, nor the last person in British history to have visions of these types. Fairy sightings, of course, continue unabated to this very day. But Ann belongs to a far more select category than the pedestrian fairy seer.

The crucial point is that Ann derived power from her fairies. She learnt to cure through their instructions: people came to Ann with broken bones, scrofula, epilepsy, agues… The fairies hurt on her behalf: causing a woman to fall. Ann was able to predict the future: she knew, thanks to the fairies, when people were coming to visit her. The fairies told her what was written in books: despite Ann being illiterate. The fairies fed Ann when she was not given human food. They seem to have given her money.

Ann, in fact, fits rather neatly into the category of what might be usefully called the ‘fairy witch’: men and women who worked magic through their contacts with the fairies. There are fairy witches recorded in Britain from the eleventh up to the nineteenth century. I suspect a careful trawl through British medieval and early modern records would bring up close to fifty. Ann offers one of the most detailed cases we have: particularly when all the relevant sources are taken together.

These fairy witches – a term, by the way, that Ann would have objected to – included such remarkable individuals as Meilyr a twelfth-century Welshman. Meilyr was able to predict the future (while living in a monastery!) thanks to his traffick with fairy-sounding ‘unclean spirits’. Or there was Bessie Dunlop who was burnt in Edinburgh in November 1576: several of the Scottish ‘fairy witches’ had unhappy ends. Bessie talked to a ghost familiar named ‘Tom’ who lived with the fairies.

Ann’s Fairy Apprenticeship

Where do fairy witches come from? We know that there were healers (who dabbled in magic) in agricultural Britain: cunning folk. Here secrets were swapped between specialists and particularly down family lines. There were even healing families who were recognised as being good with this charm or that cure. Some of these healers used the fairies (or some similar supernatural entities) to gain supernatural power.

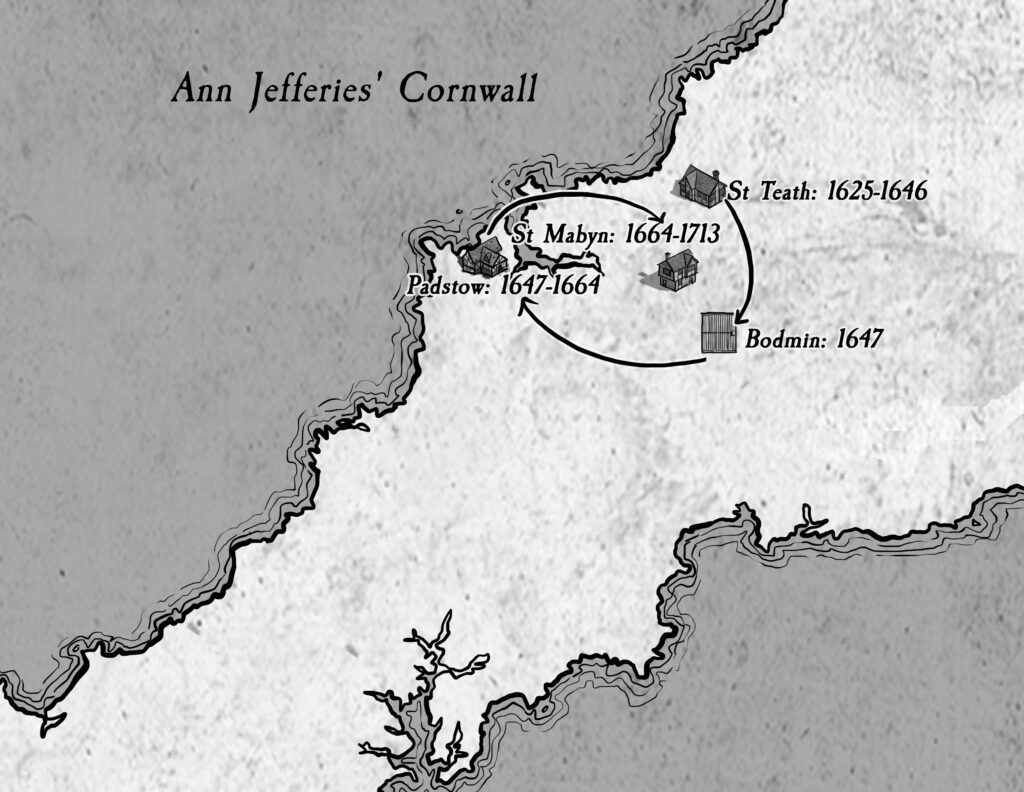

However, in the case of Ann there is no clue that anyone taught her: or that she had a magical apprenticeship with some older fairy witch. At nineteen she was working as a parish girl in the house of the well-to-do Pitt family at St Teath, Cornwall. She was clearly a fiery character: ‘She would venture at those Difficulties and Dangers that no Boy would attempt’. There she was given responsibility for Moses (one of the children in the family) for whom she had a great affection.

The fairies first made their presence felt in early 1645: Anne ‘being one day knitting in an Arbour…, there came over the Gardenhedg to her six Persons of a small Stature, all clothed in green…: upon which she was so frighted, that she fell into a kind of a Convulsion-fit’. Her ill health continued into the spring of the next year: the fairies would stay with Ann in her room, and jump out of the window as family members came to visit. Ann also, concurrently, went through a period of religious enthusiasm.

In all this time the Pitts knew nothing of her supernatural visitations: they considered Ann to be simply ill and they seem to have taken good care of her during her year-long convalescence. But Ann confessed her visions, after her mistress had hurt her leg, at Harvest 1646. Ann was told by the fairies of this accident, though she was at a distance. She, then, with remarkable self confidence, set to healing her mistress with continual leg stroking. News of Ann and her cures ‘made such a Noise over all the County of Cornwall’ that those with illnesses came to visit her.

Fame and Fear

In very late 1646 or in very early 1647 Ann was arrested. The fairies warned her that a constable was coming to take her into custody and, what is more, they told her to go with him. Ann obediently gave herself up, then, and spent several months in Bodmin in prison and in the homes of dignitaries as a prisoner, including in the house of the magistrate John Tregeagle. Tregeagle, by a remarkable coincidence, became, along with Ann, a central figure in Cornish folklore writing. He was, for generations of Cornish kids a bogie figure and many stories were told about his evil spirit haunting the moorlands and wild coasts.

Ann was presumably put under charge for suspected witchcraft. She had, after all, admitted to working with spirits; her fairies’ apparent interest in scripture would hardly excuse them to the likes of Tregeagle. Now magistrates did not, in the 1600s, go after every country healer. But Ann combined her healing practices with a line in prophecy and it was perhaps here that the authorities took worried note. This was, after all, the very delicate period following on from the end of the English Civil War (1642-1646).

Here it is worth remembering that Cornwall was a royalist county. Indeed, there is a case to be made that Cornwall was the most royalist English county in the mid seventeenth century. There had been relatively little fighting there, but Cornish soldiers had served the King, Charles I, valiantly over much of the south of England. Families like the Pitts will have, in 1646, been smarting over the defeat of the King and hoping for better times.

Ann and her fairies had strong royalist sympathies. Indeed, the fairies seem to have told Ann that ‘the King shall shortly enjoye his owne & bee revenged of his enemyes’. (They were wrong.) Ann instructed the people, too, to take up the ‘old form of prayer’: something that marked her out again as a high Anglican and a royalist. The authorities had enough on their plate with this truculent county. Parliamentarian apparatchiks like Tregeagle did not need a prophetess making the case for Charles there.

Ann seems not to have been punished. Why? On paper Ann looks as if she would have been easy meat for the gallows. Here was a woman using spirits to work magic and who admitted as much. The 1640s had seen an uptick in witch prosecutions in England: not least because of the Civil War and the religious fervour that accompanied it. This was a dangerous period for people like Ann.

How then did Ann get out of Bodmin alive? The authorities seem to have accidentally given Ann a platform by taking her to what passed as the Cornish capital at this date. It is striking that the references to her prophecies (source 1 in the source book) relate to her time under confinement there. Perhaps there was a sense that it would be best to get this woman away without the perilous spectacle of a long trial? Our sources are too slight. We can only speculate.

Nanny or Prophetess?

We know of Ann’s time with the fairies because Moses (the boy for whom Ann had special care) would later, in 1696 write about Ann’s experiences or rather his memory of the same. He did so in a pamphlet dedicated to, of all people, the Bishop of Gloucester. We have glimpses in that account of halcyon moments from Moses’ own childhood. His later life had included many disappointments. He spent much of his last years in debtor’s prison and he died in 1697.

However, since 1924, we have been aware that there are other sources for Ann. In 1647 three letters from or relating to Cornwall mention an unnamed ‘saucy’ female prophetess (fed by fairies in Bodmin), who is almost certainly Ann. The woman who we glimpse in these 1647 letters is an extraordinary self-confident figure. She reminds us of an Old Testament prophet. Take this encounter with three prelates.

Shee hath been examined by three able Divines. Shee gives a good accompt of her religion and hath the Scriptures very perfectly, though altogether unlearned. Th[e]y are fearful to meddle with, her for shee tells them to theyr faces that none of them all are able to hurte her.

Or what of her words when she was confronted with the County Committee:

Shee hath been before the committee and bids them be good in theyr office, for it will not last long.

This hardly seems the young girl who had worked in the Pitts’ house. What is happening here?

One possibility is that Ann’s difficult time in Bodmin had become the stuff of local royalist legend. Words were being put into Ann’s mouth by royalist enthusiasts in the countryside round about. In other words these accounts are about what the Cornish wanted Ann to have said.

Perhaps a simpler explanation is that Moses gave us, in his writings on Ann, an idealised child’s version of a favourite servant: one who doted on him. But Ann, after her mystic initiation, had slowly morphed into someone else entirely. She was now an assertive fairy mahdi who felt that she had fairy right on her side.

Goodbye to the Fairies

Ann’s later career as a fairy witch is all but lost to us. She was not allowed to return to the Pitts’ house at the end of her time in Bodmin. She moved instead to the house of Mrs. Francis Tom near Padstow and there she ‘did many great Cures’. She, then, aged about 29, married and moved to St Mabyn. Pitt believed that the fairies had ‘forsook’ her: I, thinking of other fairy mystics, would not be so sure. But, if the fairies continued to commune with Ann in later years, they had evidently, at a certain point, become a private matter.

Aged 70, Anne told one of Moses’s agents while refusing to help Moses with his fairy pamphlet:

she would not have her Name spread about the Country in Books or Ballads of such things, if she might have five hundred Pounds for the doing of it.

Chronology

‘Source’ references are for the source book. Note that Ann’s baptismal, marriage and funeral name was ‘Elizabeth’!

1625: Ann christened ‘Elizabeth’ at St Teath, 13 Feb (see source 12).

1639: 12 March, Baptism of Moses Pitt (source 9).

c. 1640: Ann comes to the Pitts as a parish girl: she ‘lived several Years’ with the family (source 2).

1645: Ann sees fairies and becomes ill in very early 1645 (source 2).

1646: March, surrender of Royalists in Cornwall; the end of the English Civil War.

1646: April, Ann was in the ‘Extremity of her Sickness’ (source 2).

1646: At ‘harvest’ she cures Moses’ mother and reveals her fairy visions. She stops eating (source 2). Note that the period of the sick coming to be cured at the Pitts’ house lasts at most about four months.

1646: Christmas, Ann eats with the family (source 2).

1646-1647: Between Christmas 1646 and February 1647 Tregeagle has Ann brought to Bodmin (source 2). In the next months she was three months in the prison, a time in the Mayor’s house and a time in Tregeagle’s house (source 1 and 2). Possibly not in that order.

1647: February to April news about Ann’s prophecies in Bodmin (source 1). She had by February been before the County Committee and three divines.

1647-1648: Late in the year or perhaps in 1648 Ann is sent to the house of Mrs. Francis Tom (source 2) ‘near Padstow’. She stays there ‘a considerable time’. At some point she went (source 2) to live with her brother: though we don’t know where that was.

1664: Ann’s marriage at St Mabyn, ‘William Werrin and Elizabeth Jeffery’ (source 12).

c. 1680: Meal with Moses Pitt and Bishop Fowler where Ann is discussed (source 2).

1691: Moses Pitt begins to try and get information from Ann for his pamphlet (source 2).

1693: Moses Pitt sends a second agent to Ann (source 2).

1696: Moses Pitt publishes his pamphlet (source 2).

1696: Ann still alive and in Cornwall (source 2).

1696: December, Moses Pitt adds information (source 3) to his original account in a letter to William Turner in December.

1697: Death of Moses Pitt (source 9).

1713: An ‘Elizabeth Werrine’ dies at St Mabyn (27 Oct) (source 8, note).