The Tiv and Hamlet September 12, 2010

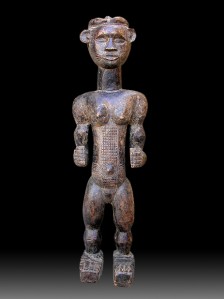

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary, Modern , trackback Laura Bohannan (aka Elenore Smith Bowen) was an anthropologist who came out of Oxford in the late 1940s. She did research with her husband Paul among the Tiv of Nigeria and the pair published several books on this federation over the next two decades. However, Bohannan also gave a remarkable BBC radio talk entitled, depending on editions, ‘Miching Mallecho, That Means Witchcraft’ or ‘Shakespeare in the Bush’.

Laura Bohannan (aka Elenore Smith Bowen) was an anthropologist who came out of Oxford in the late 1940s. She did research with her husband Paul among the Tiv of Nigeria and the pair published several books on this federation over the next two decades. However, Bohannan also gave a remarkable BBC radio talk entitled, depending on editions, ‘Miching Mallecho, That Means Witchcraft’ or ‘Shakespeare in the Bush’.

Beachcombing was first given a printed version of the talk by his trusted bookseller Dray almost twenty years ago and on rereading it is still grateful.

The worst thing that can be said about Bohannan’s talk/essay is that is has become the play thing of sociologists and cultural studies majors the western world over despite its rather ‘patronising’ and ‘dated’ tone. The comic element in the writing means that the Tiv, at times, jump about on their strings like anthropological Ewoks.

The best thing is that it is a very amusing, literate description of the attempt of one self-confident English woman to ‘educate’ a tribal people in the canons of western literature, telling them the story of Hamlet. But, of course, it is she who is educated as the ‘universality’ and ‘timelessness’ of Shakespeare are plucked and then pulled apart.

The old man handed me some more beer to help me on with my storytelling. Men filled their long wooden pipes and knocked coals from the fire to place in the pipe bowls; then, puffing contentedly, they sat back to listen. I began in the proper style, ‘Not yesterday, not yesterday, but long ago, a thing occurred. One night three men were keeping watch outside the homestead of the great chief, when suddenly they saw the former chief approach them.’

‘Why was he no longer their chief?’

‘He was dead,’ I explained. ‘That is why they were troubled and afraid when they saw him.’

‘Impossible,’ began one of the elders, handing his pipe on to his neighbor, who interrupted, ‘Of course it wasn’t the dead chief. It was an omen sent by a witch. Go on.’

Slightly shaken, I continued.

That ‘slightly shaken’ sets the tone for the whole encounter. Take Laura’s attempts to explain the moment that Hamlet comes face to face with his father’s ghost, something that is surely easily explained?

More hopefully I resumed, ‘That night Hamlet kept watch with the three who had seen his dead father. The dead chief again appeared, and although the others were afraid, Hamlet followed his dead father off to one side. When they were alone, Hamlet’s dead father spoke.’

‘Omens can’t talk!’ The old man was emphatic.

‘Hamlet’s dead father wasn’t an omen. Seeing him might have been an omen, but he was not.’ My audience looked as confused as I sounded. ‘It was Hamlet’s dead father. It was a thing we call a ghost.’ I had to use the English word, for unlike many of the neighboring tribes, these people didn’t believe in the survival after death of any individuating part of the personality.

‘What is a ‘ghost?’ An omen?’

‘No, a ghost is someone who is dead but who walks around and can talk, and people can hear him and see him but not touch him.’

They objected. ‘One can touch zombis.’

‘No, no! It was not a dead body the witches had animated to sacrifice and eat. No one else made Hamlet’s dead father walk. He did it himself.’

‘Dead men can’t walk,’ protested my audience as one man.

I was quite willing to compromise.

‘A ‘ghost’ is the dead man’s shadow.’

But again they objected. ‘Dead men cast no shadows.’

‘They do in my country,’ I snapped.

The old man quelled the babble of disbelief that arose immediately and told me with that insincere, but courteous, agreement one extends to the fancies of the young, ignorant, and superstitious, ‘No doubt in your country the dead can also walk without being zombis.’ From the depths of his bag he produced a withered fragment of kola nut, bit off one end to show it wasn’t poisoned, and handed me the rest as a peace offering.

The piece ends with the Tiv taking over the storytelling from the frustrated Bohannan: they conclude that – pace T.S. Eliot – Laertes had killed Orphelia by magic to sell her body to the witches. Hamlet and his tiresome step-father was apparently just a side story.

‘Sometime,’ concluded the old man, gathering his ragged toga about him, ‘you must tell us some more stories of your country. We, who are elders, will instruct you in their true meaning, so that when you return to your own land your elders will see that you have not been sitting in the bush, but among those who know things and who have taught you wisdom.’

Beachcombing has a large lost in translation file: he is always interested though in more material. drbeachcombingATyahooDOTcom