C-section by Banana Wine December 19, 2010

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackback

Beachcombing is going to break several rules today. First, he is going to write on the same topic two days in a row: apologies, apologies, but the C-section question has even excited him out of his recent Atlantis itch. Then, second, he is writing two posts on the same day. This is in part natural enthusiasm and in part because he thinks the chances that he will be cut off from the world by snow are mounting rapidly.

While looking into the whole question of C-sections Beachcombing came across a fascinating nineteenth-century account from Uganda. Our hero is the Briton Robert Felkin who, aged 25, travelled down into central Africa in 1878 as part of the Church Missionary Society. Beachcombing knows about Felkin because he employed his knowledge of eclipses to terrify the local king, predicting the darkening of the sun: something that Tintin would later do in the Andes to prevent himself Captain Haddock being burnt alive.

The following account by Felkin was given in 1884 in the Edinburgh Medical Journal and draws on his time in the dark continent:

So far as I know, Uganda is the only country in Central Africa where abdominal section is practised with the hope of saving both mother and child. The operation is performed by men, and is sometimes successful; at any rate, one case came under my observation in which both survived. It was performed in 1879 at Kahura. The patient was a fine healthy-looking young woman of about twenty years of age. This was her first pregnancy…

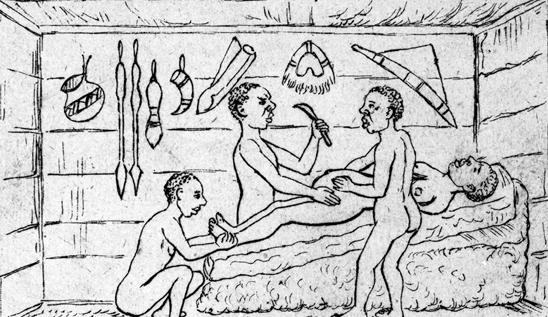

The woman lay upon an inclined bed, the head of which was placed against the side of the hut. She was liberally supplied with banana wine, and was in a state of semi-intoxication. She was perfectly naked. A band of mbuga or bark cloth fastened her thorax to the bed, another band of cloth fastened down her thighs, and a man held her ankles. Another man, standing on her right side, steadied her abdomen. The operator stood, as I entered the hut, on her left side, holding his knife aloft with his right hand, and muttering an incantation. This being done, he washed his hands and the patient’s abdomen, first with banana wine and then with water. Then, having uttered a shrill cry, which was taken up by a small crowd assembled outside the hut, he proceeded to make a rapid cut in the middle line, commencing a little above the pubes, and ending just below the umbilicus. The whole abdominal wall and part of the uterine wall were severed by this incision, and the liquor amnii escaped; a few bleeding-points in the abdominal wall were touched with a red-hot iron by an assistant. The operator next rapidly finished the incision in the uterine wall; his assistant held the abdominal walls apart with both hands, and as soon as the uterine wall was divided he hooked it up also with two fingers.

The child was next rapidly removed, and given to another assistant after the cord had been cut, and then the operator, dropping his knife, seized the contracting uterus with both hands and gave it a squeeze or two. He next put his right hand into the uterine cavity through the incision, and with two or three fingers dilated the cervix uteri from within outwards. He then cleared the uterus of clots and the placenta, which had by this time become detached, removing it through the abdominal wound. His assistant endeavoured, but not very successfully, to prevent the escape of the intestines through the wound. The red-hot iron was next used to check some further haemorrhage from the abdominal wound, but I noticed that it was very sparingly applied. All this time the chief ‘surgeon’ was keeping up firm pressure on the uterus, which he continued to do till it was firmly contracted. No sutures were put into the uterine wall. The assistant who had held the abdominal walls now slipped his hands to each extremity of the wound, and a porous grass mat was placed over the wound and secured there. The bands which fastened the woman down were cut, and she was gently turned to the edge of the bed, and then over into the arms of assistants, so that the fluid in the abdominal cavity could drain away on to the floor. She was then replaced in her former position, and the mat having been removed, the edges of the wound, i.e. the peritoneum, were brought into close apposition, seven thin iron spikes, well polished, like acupressure needles, being used for the purpose, and fastened by string made from bark cloth. A paste prepared by chewing two different roots and spitting the pulp into a bowl was then thickly plastered over the wound, a banana leaf warmed over the fire being placed on the top of that, and, finally, a firm bandage of mbugu cloth completed the operation.

Until the pins were placed in position the patient had uttered no cry, and an hour after the operation she appeared to be quite comfortable. Her temperature, as far as I know, never rose above 99.6°F, except on the second night after the operation, when it was 101o F, her pulse being 108. The child was placed to the breast two hours after the operation, but for ten days the woman had a very scanty supply of milk, and the child was mostly suckled by a friend. The wound was dressed on the third morning, and one pin was then removed. Three more were removed on the fifth day, and the rest on the sixth. At each dressing fresh pulp was applied, and a little pus which had formed was removed by a sponge formed of pulp. A firm bandage was applied after each dressing. Eleven days after the operation the wound was entirely healed, and the woman seemed quite comfortable. The uterine discharge was healthy. This was all I saw of the case, as I left on the eleventh day. The child had a slight wound on the right shoulder; this was dressed with pulp, and healed in four days.’

Beachcombing is bound to note that Felkin was fairly sceptical about the efficacy of this operation – it was, remember, only ‘sometimes successful’. Beachcombing feels bound to say too that in 1879 doctors in London were only ‘sometimes successful’, though this was a period when they were rapidly improving.

Nevertheless if this really was a traditional method – not one borrowed from earlier western travellers – then here is the proof that c-sections could be carried out in a pre-modern community.

Is there any other evidence of early and successful c-sections from elsewhere in the world? drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

Beachcombing recalls the truly horrible Robin of Sherwood and a scene with an Arab henchman of Robin carrying out a C-section and earning the perpetual gratitude of Friar Tuck. Is it possible that someone employed by Kevin Costner stumbled on a reference from the Islamic world that has so far eluded Beachcombing and then decided to have fun with it?

Boh?

Beachcombing will end this brief two day caesarean mania by paying tribute to Inés Ramírez who in 2000, in a remote Mexican village, performed a caesarean section on herself and came through the experience with her and her son alive! ‘Ramirez said she thinks she operated on herself for about an hour before extricating her child and then fainting. When she regained consciousness, she wrapped a sweater around her bleeding abdomen and asked her 6-year-old son, Benito, to run for help. Several hours later, Cruz and a second health worker found Ramirez alert and lying beside her live baby. Cruz sewed her 17-cm incision up with a regular needle and thread. The two men lifted mother and child onto a thin straw mat, lugged them up horse paths to the town’s only road, then drove them to the clinic over two hours away.’ Surely she would not have survived though without subsequent medical help.

When Beachcombing shared these details with a class of six twenty year old girls last summer, there was outrage. It is the only time in his teaching career that students actually told Beachcombing – imperatively – to shut up.