Beethoven and the Fire from Heaven January 20, 2011

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackbackBeachcombing recently offered three posts on the subject of lightning, trying to dig up some occasions when a bolt has changed, however modestly, the course of human history. Beachcombing must confess though to being slightly disappointed that lightning has not done more for (or against) humanity: any other lightning offers – drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com.

And, in fact, his last fire from the heavens contribution for a while did not change history, but it did make a moment of history particularly vivid and Beachcombing offers up the following extraordinary account from the pen of Anselm Hüttenbrenner as a WIBT (Wish-I’d-been-there) moment.

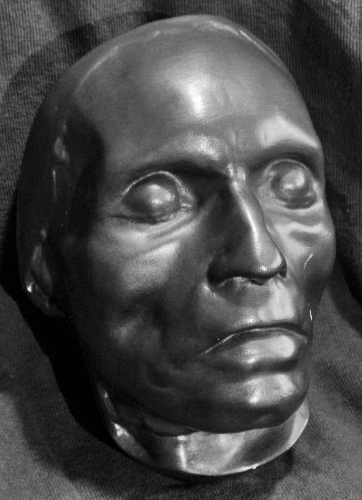

It is the early evening of the 26 March 1827 and it is almost over for Beethoven whose body has been winding down for the last three days. The old warrior is coming to the end of his greatest composition.

After Beethoven had lain unconscious, the death-rattle in his throat from 3 o’clock in the afternoon till after 5, there came a flash of lightning accompanied by a violent clap of thunder, which garishly illuminated the death-chamber. (Snow lay before Beethoven’s dwelling.) After this unexpected phenomenon of nature, which startled me greatly, Beethoven opened his eyes, lifted his right hand and looked up for several seconds with his fist clenched and a very serious threatening expression as if he wanted to say: ‘Inimical powers, I defy you! Away with you! God is with me!’ It also seemed as it, like a brave commander he wished to call out to his wavering troops: ‘Courage, soldiers! Forward! Trust in me! Victory is assured’ When he let the raised hand sink to the bed, his eyes closed half-way. My right hand was under his head, my left rested on his breast. Not another breath, not a heartbeat more! The genius of the great master of tones fled from this world of delusion into the realm of truth! I pressed down the half-open eyelids of the dead man, kissed them, then his forehead, mouth and hands.

Hüttenbrenner, a composer who suffered from the Vasari complex – the most famous thing he ever did was watch Beethoven die – then had a lock of hair cut from the corpse.

The tears are dropping down Schroeder’s cheeks at this point, while Beachcombing, who is not such a Beethoven fan, is still stunned into silence by the image: Beethoven the greatest of all the Romantics dying a death commensurate with his life. You’d have to jump into a volcano singing opera to come close to this.

Some modern historians have had the indecency to question whether Hüttenbrenner didn’t invent or embellish his account – he was alone in the room or with just one of Beethoven’s female relations when the moment came. Happily for those who like melodrama in history Dr Schindler’s more clinical and sensible account is not at odds with that of Hüttenbrenner: ‘A frightful struggle between death and life began… until a quarter to six on the evening of the twenty six March, when during a heavy hailstorm the great composer gave up the spirit.’ The Viennese metereological station also recorded thunder storms – yes, someone checked…

There may also be another reason though for believing Hüttenbrenner’s account – a medical one. Beet died of heptic failure and in the closing phases of heptic failure patients react strongly to sudden strong stimuli like bright light. Beethoven’s clenched fist may then have been an involuntary spasm of his illness: an exaggerated version of the way our heart skips when someone taps us on our shoulder in the queit of the library.

However, that rather takes away from the image – deconstructing rainbows and all that – so Beechcombing is going to immediately relegate this to his unimportant information file.