The Werewolf Faith in Nineteenth-Century France January 28, 2011

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackback

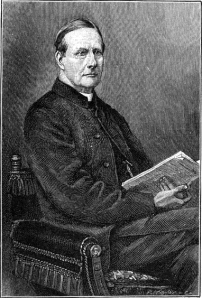

Since beginning this blog eight months ago Beachcombing has had various itches including elephants, Atlantis (to be continued), birds and lightning. But none has bitten so deeply as the werewolf. Indeed, Beachcombing has sketched out another ten posts on the men and women who were furry on the inside. He even, damn it, started vaguely jotting down a contents list for a werewolf book: is it Beachcombing’s imagination or is there a lack of anything truly top notch out there? But he has the sense that now is the time to call a pause, at least for a couple of months, until the summer sun is back above Little Snoring and vitamin D has started to flood Beach’s system again. So he will bow out paying tribute to the man who many years ago first introduced the werewolf to polite English society: that priestly Victorian loon, exaggerator and bizarrist, Sabine Baring-Gould.

Beachcombing treasures the following account because it is the kind of story that doesn’t normally get told in the nineteenth century (when it would still have been possible to record these things). Back then there were accounts – in the corners of newspapers – of alleged werewolf activity. There were scholarly and sub-scholarly books on folk-stories including werewolves. But here, instead, is simple belief: the werewolf faith, alive and well among a small French village c. 1850.

SB-G has been to visit a Gaulish relic at La Rondelle, near Champigni [Poitiers] and is heading back to his hotel.

A small hamlet was at no great distance, and I betook myself thither, in the hopes of hiring a trap to convey me to the posthouse, but I was disappointed. Few in the place could speak French, and the priest, when I applied to him, assured me that he believed there was no better conveyance in the place than a common charrue with its solid wooden wheels; nor was a riding horse to be procured. The good man offered to house me for the night; but I was obliged to decline as my family intended starting early on the following morning.

Out spake then the mayor: ‘Monsieur can never go back tonight across the flats, because of the, the…’ and his voice dropped ‘the loup-garoux’.

‘He says that he must return!’ replied the priest in patois ‘But who will go with him?’

‘Ah, ha! M le Curé. It is all very well for one of us to accompany him, but think of the coming back alone!’

‘Then two must go with him’, said the priest, ‘and you can take care of each other as you return’.

The loup-garoux though has been spotted that very night.

‘[A villager] was down by the hedge of his buckwheat field, and the sun had set, and he was thinking of coming home, when he heard a rustle on the far side of the hedge. He looked over and there stood the wolf as big as a calf against the horizon, its tongue out, and its eyes glaring like marsh-fires. Mon Dieu! Catch me going over the marais tonight. Why what would two men do if they were attacked by that wolf-fiend?’

‘It is tempting Providence’ said one of the elders of the village, ‘no man must expect the help of God if he throws himself willingly in the way of danger. Is it no so M. Le Curé? I heard you say as much from the pulpit on the first Sunday in Lent, preaching from the Gospel.’

‘That is true’, observed several, shaking their heads…

Sabine though is made of sterner stuff and, Beachcombing senses, rather enjoys lording it over the French peasantry.

‘Never mind’, said I, who had been quietly listening to their patois, which I understood. ‘Never mind, I will walk back by myself, and if I meet the loup-garoux I will crop his ears and tail and send them to M. le Maire with my compliments.’

A sigh of relief from the assembly as they found themselves clear of the difficulty.

‘Il est Anglais [he is English]’, said the mayor, shaking his head, as though he meant that an Englishman might face the devil with impunity.

S B-G then undertakes the journey alone though, the reader senses, with a heartbeat a little above the regular: ‘that this district harboured wolves is not improbable and I confess that I armed myself with a strong stick at the first clump of trees through which the road dived.’

If Beachcombing were writing a short story he would have the village priest jump out on Sabine from behind that clump to give the loveable Victorian prig a lesson in good manners. How the curate would have run.

Beachcombing is on the look out for similar accounts of the werewolf faith: especially from supercilious Anglo-Saxons like Sabine: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com But he promises he won’t write about werewolves again for two whole moons.