Fairy Jousting? October 26, 2012

Author: Beach Combing | in : Medieval , trackbackThis tale comes from an early thirteenth-century Latin collection of mirabilia. It has not, to the best of Beach’s knowledge been associated with fairies, but reading it eight hundred years after its composition, there seem to be some fey hints worth flagging up. Note that the Latin below comes from an early edition where there has been excessive ‘normalisation’. It has no scientific value, it is just included to give some idea of where the English translation (Banks and Binns) is coming from.

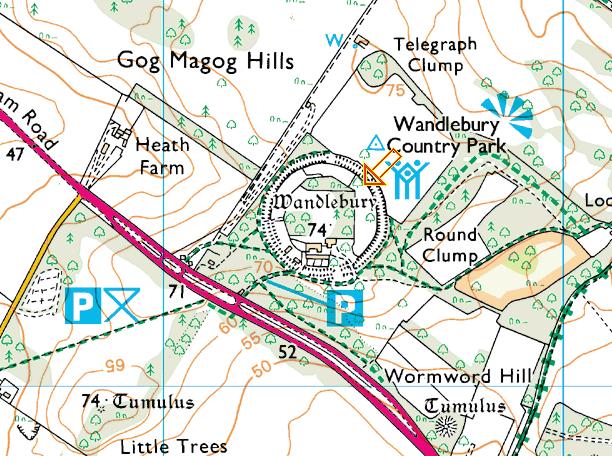

In England, near the outskirts of the diocese of Ely, there is a town called Cambridge. In its territory, not far from the town, is a place which they call Wandlebury, because the Vandals pitched camp there when they were laying waste whole areas of Britain, cruelly slaughtering the Christians.

In Anglia ad terminos episcopatus Eliensis est castrum, Cantabrica nomine, infra cuius limites e uicino locus est, quem Wandlebiriam dicunt, eo quod illic Wandali partes Britannie seua Christianorum peremptione uastantes, castra metati sunt.

Now, of course, Wandlebury has nothing to do with the Vandals. It probably means Waendal’s Fort and the best guess is that Waendal was a mythological figure from out of the hellish and now happily forgotten Anglian pantheon. The fort dates back to Iron Age times and would make an excellent home for the fairies of English legend: the raised buttresses and the hints of an underground dwelling. Anyway, back to the tale…

Now in the place on top of a slight hill where the Vandals set up their tents, a plateau is enclosed by earthworks forming a circle, open for access by a single gate-like approach. There is a widely-attested report, going back to very ancient times, that if a knight goes onto this plateau at dead of night when there is a moon shining, and shouts: ‘Let a knight come against a knight!’, a knight will immediately come forward to meet him, ready to engage in combat; their horses charge together and he either overthrows his opponent or is overthrown himself. But there is a condition to be fulfilled first: the knight has to go through that entrance into the enclosure on his own, though there is nothing to prevent his companion from looking on from outside.

Ubi uero ad monticuli apicem fixere tentoria; planicies in rotundum uallatis circumcluditur, unico ad instar portalis aditu patens ad ingressum. In hanc campi planiciem ab antiquissimis temporibus colitur famaque uulgo testatur post noctis conticinium lucente luna si quis miles ingrediens exclamat: ‘Miles contra militem yeniat’ statim ex aduerso miles occurret qui ad congrediendum paratus, concurrentibus equis, aut resistentem deiicit aut deiicitur. Uerum ad cautelam praeambulum est, quod intra aditus illius septa miles solus habet ingredi; ab exteriore conspectu sociis non arctandis.

Let’s get the geography and etiquette of this right. The human knight rides into the circle (see map above) through the gateway. His squire can then watch him from the buttresses (now treed over) but he cannot enter the dueling area.

To lend credibility to this matter, I am going to describe an exploit well known to many people, which I got the local inhabitants to recount to me. There was in Great Britain, a little time ago [paucis exactis diebus], a knight, most gallant in arms, endowed with all the virtues, second to few among the barons in power, and inferior to none in prowess. His name was Osbert Fitz Hugh.

Ad huis rei fidem rem gestam et multis uulgo cognitam subjungo, quam ab incolis et indigenis auditui meo subieci. Erat in Britannia majore, paucis exactis diebus, miles in armis strenuissimus, omnibus uirtutibus dotatus, inter barones paucis secundus in potentia, nullique inferior in probitate. Osbertus Hugonis nominatus est.

Osbert Fitz Hugh was the name of a knight who flourished in the 1130s and 1140s. However, we should note, before we get excited about eye witness accounts and the like, that in a second version of this story the hero is called Albert! Wandlebury appears interestingly in several Arthurian tales.

One day [Osbert] came to stay in the town of which I have spoken. It was the harsh winter-season and in the evening after dinner the household of his wealthy host gathered around the hearth and, as is the custom among the nobility, turned their attention to recounting the deeds of people of old, or else settled down to listen. In due course the marvel I have mentioned came up, and was described by the residents. And so, being a man of prompt action, and wanting to test by experience the truth of the tale he had listened to so avidly, he chose one of the noble squires, and with this companion set off for the place. When he got near to the designated spot, the knight, clad in mail, mounted his steed; he dismissed the squire, and entered the field alone. He duly shouted to discover the other, and at the sound of his voice a knight, or something like a knight, came rapidly towards him from the other side, similarly armed, as it appeared.

Hic aliquo die castrum memoratum ut hospes ingreditur, et cum in hyemis intemporie post coenam noctu familia diuitis ad focum, ut potentibus moris est, recensendis antiquorum gestis operam daret et aures accommodaret, tandem occurrit ab indigenis praetaxatum mirabile recensitum. Uir ergo strenuus, ut, quod auribus hauserat, rei ipsius experientia probaret; unum de nobilibus armigeris eligit, quo comite locum adiit; ad ostensum locum loricatus miles apropians, sonipedem ascendit, dimissoque domicello, campum solus ingreditur. Exclamat miles, ut alterum inueniat, et ad uocem ex opposito miles aut instar militis celer occurrit, peraeque, ut uidebatur, armatus.

The hero in the mirror, a ghostly shiver that comes out of several medieval legends.

To tell it briefly, they put up their shields, they aimed their spears, their horses charged together, and the riders struck each other with an exchange of blows; at this point Osbert, having avoided the lance of the other knight, whose blow missed its mark thanks to some slippery ground, powerfully knocked his adversary to the ground. He fell, but rose again in a trice, and when he saw Osbert leading his horse away by the reins as the spoils of the fight, he brandished his lance, and hurling it like a javelin he pierced Osbert’s thigh with a cruel blow. On his side our knight, either not feeling the blow and the wound in the joy of victory, or pretending not to, emerged from the field victorious, while his adversary disappeared. He handed over to the squire the horse he had taken as his spoils; it was large in stature, sprightly in movement, and very handsome in appearance.

Quid plura? Ostensis clipeis, directis hastis equi concurrunt, equites impulsibus mutuis concutiuntur, et elusa iam alterius lancea ictuque euanescente per lubricum, Osbertus aduersarium suum potenter impelllt ad casum. Cadens et sine mora resurgens, ut Osbertum per lora conspicit equum ex causa lucratiua abducere, lanceam succutit, et dum eam modo jaculi missilis emittit, femur Osberti ictu atrocissimo transfodit Ex aduerso miles noster, aut prae gaudio uictoriae ictum uulnusque non sentiens aut dissimulans, disparente aduersario campum uictor egreditur, equum lucratom armigero tradit statura grandem, leuitate agilem, et in apparentia pulcherrimum.

The household came trooping out to meet the noble gentleman on his return, and marvelled at what had happened. They rejoiced at the fall of the defeated knight, and praised the valour of this baron who had so distinguished himself. Osbert took off his knightly armour, and when he was undoing his iron shoes, he saw that one was full of clotted blood: his friends were shocked at the wound, but the lord disdained to fear. The townsfolk were roused and gathered round; even people who had been sound asleep were soon brought wide-awake by the mounting excitement. The horse, the proof of this triumph, was being held with its bridle unslackened, exposed to public view: its eyes were wild, its neck stiff, its coat black; the knight’s saddle and the whole saddle cloth were likewise black. But as soon as the cock-crowed, the horse, bucking violently, foaming at the nostrils, and pounding the ground with its hooves, broke the reins by which it was held, and regained its native freedom, it took flight and though pursued was lost to sight. Our noble friend had a permanent token of that indelible wound: ever year, at that same moment of the night when it came round again, the wound broke open afresh, although it had healed over on the surface. And so it came to pass that after a few years the distinguished knight crossed the sea and, fighting with redoubled courage against the pagans, gave his life to divine service and his soul to God.

Regredienti uiro nobili familiaris turba occurrit, euentum miratur, casum dejecti militis gratum habens, et strenuitatem tam illustris baronis commendans. Exuit Osbertus arma militaria, et cum caligas ferreas discalcearet unam sanguine coagulato uidet impletam. Stupet familia de uulnere, sed dominus indignatur timere. Concunit excitas populus, et quos somnus ante presserat, excrescens admiratio ducit ad uigilandum. Testis triumphi equus freno non demisso tenetur, ad publicum conspectum expositus, oculis toruis, ceruice erecta, pilo nigro, sella militari, totoque substemio itidem nigro. Iam galli cantus aduenerat, et equus saltibus aestuans, naribus ebulliens, pedibus terram pulsans, loris, quibus tenebatur, disruptis, in natiuam recepit se libertatem; fuga facta insecutus disparuit. Et nobilis noster id infixi uulneps perpetuum habuit monimentum, quod singulis annis illo eodem noctis renouatae momento uulnus, in superficie cura superductum, recrudescebat Unde factum est, quod post paueos annös miles illustris transfretauit, et sub multiplicata pugnandi contra paganos strenuitate uitam diuino ministerio animam Deo reddidit.

Ah, my Lord, it was the wound that never healed…

Perhaps in the end an argument over whether this was a fairy foe or not misses the point. After all, what was a fairy in the twelfth century? A tiny winged tinkerbell (no), or anything supernatural that could be jammed into an oak chest labelled ‘faery’ (yes)? For what it is worth though the disappearance of fairies or their animals at cock crow is well established, as though is the disappearance of demons. And, yes, black is not particularly a fairy colour… Other thoughts on the jousters fairy credentials (or lack of the same): drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

Kris writes in, 30 Jun 2016, ‘I just read you piece, and would like to thank you for it, as I was looking for an earlier source for the much quoted Walter Scott version. I also appreciated your mention of the “mirror” as I might have overlooked that. The OS map was also very handy. Here are my thoughts, in case you are interested. On first reading it is the information about the horse which stands out, and especially how the characters interact with it. 1) the leading away of the horse by the squire seems to be the impetus for the fairy knight throwing the spear, possibly indicating the importance of the horse to him. If he was trying to get the horse back, though, surely he would have aimed at the squire. While the wound isn’t serious, its annual reappearance is provocative, and obviously meant as a reminder or lesson. 2) The horse’s escape seems to emphasise its loyalty, rather than supernatural abilities – as anyone who handles horses would know, they can easily break loose if they try hard enough.