Families and the Durability of Memory November 22, 2012

Author: Beach Combing | in : Actualite, Contemporary, Modern , trackbackHow long can memories remain in a family? We have played these games before, of course. Just a couple of weeks ago Beach was imagining his daughter telling his great great grandchildren about the time their great, great, great, great grandfather survived an Italian attack in the Mediterranean, a hundred and fifty years after the event. That story potentially could survive in a family for almost two hundred years if those young remember the account to the end of their lives. Beach also, back in the early days of the blog, speculated about whether there was not a way, Musgrove Ritual style, that a family could keep a memory alive for even longer: the only post on this blog for which a prize has been given. But there is a problem. The theory of the hundred and fifty year old story sounds dandy, but… Well damn it, when the present author was a young boy nobody recalled his great, great, great, great grandfather’s killing the French at Waterloo. This leaves a bitter taste in the mouth.

Beach’s parents come from, on the one hand, upper middle class and, from the other, working class backgrounds, both classes with a strong sense of history. But the memories that are passed down are fairly jejune. There are rumours that the working class family came over from Ireland some time in the nineteenth century: but when Beach’s mother did genealogical research this seemed not to be the case. We are back to the reliability (or the lack of reliability) of oral traditions. On the other side, there is a memory of the family losing their manor house in Norfolk, Wacton Hall – very late nineteenth century? – as the squirarchy disintegrated (‘bugles calling for them from sad shires’). And also the formulaic fact passed down that a great grandfather was one of nineteen officers from his battalion to survive the Battle of the Somme, figures that still take the breath away almost a century on. In the best case scenario here we are talking about a pathetic hundred or a hundred and twenty years of memory.

Mrs B who comes on one side from an aristocratic background had a great grandfather who fought at bloody Adowa (1896) and brought back a small Somalian tea cup to celebrate his survival. I suspect the story has stayed alive only because the small Somalian tea cup is sitting on the shelf of an aunt. We are still at a century and that memory will die in the present generation as Mrs B has not the least interest in the fact that her bloodline was almost wiped out by some very angry Ethiopians.

Beach got one email in response to an earlier post from Nathaniel (for which many thanks):

The oldest word-of-mouth story in my family goes back to about 1880 (my mother talking about what she’d hear of her grandmother or maybe great-grandmother, if I recall right) [that ‘recall right’ gets to the heart of the problem]. Several stories from the early 1900s that I heard directly from grandparents and grand aunts about their experiences of those times. It seems like most young people today (including my son) aren’t much interested in the past, either family or historical. Hopefully enough are to keep these stories alive.

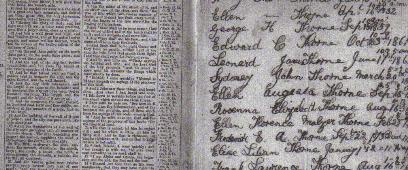

So can anyone beat Beach c. 1890 or Nathaniel’s 1880 or does anyone, out of interest, go to the other extreme and not have memories going back to the last war: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com Note that famous ancestors who are in books disqualify you. No point allowing writing to spoil the purity (ahem) of oral memories. The death of the family bible was a tragedy…

***

22 Nov 2012: When I asked this question I made two assumptions. Namely that as many readers are American family memories of (i) emigration and (ii) the Civil War – two unquestionably traumatic events – would be foremost in family memories. This was only partially true. Here are some of the best of the crop. Aldous Huxley provides the oldest memories yet: ‘On my Dad’s side, my great-grandfather apparently claimed that a McArthur (that’s us, my family) was the first to swim the Firth of Forth with a keg of whiskey on his back: This would probably place it before 1890 opening of the firth bridge, and he left Scotland in about 1887. Jokes aside there were a lot of stories my grandfather had about his family, but the only really dramatic one was that when the family moved to Canada so Great-Grandfather could work in the silver mines in Ymer BC in the 1890s and his family stayed at Salmo.His infant daughter became very ill in the winter during a blizzard in 1898. He, his wife with the baby, and a friend went down to the railroad, stole a railroad push car and went down the line to where the nearest doctor was, 7 miles or so in Ymer. During the travel the baby girl died. I know these things because my dad took notes while pumping information out of my grandfather one Christmas when I was a kid. Dad later wrote a book, but I do remember him telling the story a couple of times. On my Mom’s side, the family story was that my great-grandfather came out on a wagon train to the Oregon Territory in 1845, they took the cutoff through the Blue Mountains (the Meek cutoff in NE Oregon) got delayed, ran low on provisions and nearly starved to death. He married and settled on a donation land claim in about 1851.’ Tacitus from Detritus writes ‘My family lore goes back to 1862. Supposedly my great, great grandmother was a young bride in 1862 when the Sioux uprising occurred. Burying the family valuables in the floor of the log cabin they lit out for safer environs. The tale, much embellished, was told to my uncle who passed about five years back at age 90. He told it to my generation incessantly. My kids have heard it too, so it may last a while. So, g-gma to her gson to me and to mine. As to the actual chest in which said valuables were buried, I have significant doubts. 1862 to 2012….150 years. But surely someone will top that.’ Invisible writes: ‘On the oral tradition. My great-great-great-Grandfather Oliver was killed at the battle of Chickamauga, September 19, 1863 leaving a widow and two daughters. His wife received a Civil War widow’s pension and became engaged to a gentleman who then jilted her to marry one of her daughters. She said in 1880 that it didn’t really matter, because “she wouldn’t give up her pension, not for any man.” Her soldier husband’s body was never found (as happened to a number of soldiers at Chickamauga). His oldest daughter would never turn away a tramp, thinking it might be her father come back. This quote and anecdote has come down in the family through the younger daughter, who told my great-grandmother, who told my aunt, who told me. In a different sort of transmission, this same aunt heard from a man who bought the house where my 3G Grandfather Oliver lived before he went away to the War. He has been researching the family and somewhere he found an account of Oliver in 1861 nailing a coin onto the door frame of the dining room and saying that he would take the coin down when he returned. The new owner found the coin still in place. (He has offered to show us documentation and coin when we visit.) There is also a story from before the family left Switzerland in the early 1880s. One of our ancestors was a baker. He went hunting and died in a shooting accident; they served the breads he had baked that morning at his wake that evening. My grandfather was the youngest of 12 exceptionally long-lived children so he heard much of the ancestral lore. The entire clan was fond of telling family stories so I have a reasonable expectation that these tales are true.’ EH writes, meanwhile, ‘My grandfather was born in 1898, and lost most of his hearing in WWI — in a few years I can tell my kids of that hundred year old memory, and another decade on I can tell them about how he had opinions of Al Capone (or “Caponey” as he pronounced it) based on knowing people who knew people, rather than based on reading things in the headlines. That’ll be a hundred year one there. On the other side of the family, I am told that my maternal grandfather, a minister’s child on the Navajo reservation, was nicknamed Nayenezgani, the Monster Slayer, by his playmates. That seems almost too cool to be true. But I heard it from him. That’s probably not even close to a hundred year old memory; he was considerably younger than my paternal grandfather.’ Thanks AH, Tacitus, Invisible and EH!

3 Dec 2012: Kiki writes: I have a piece of family oral tradition that goes back to 1813. One of my great grandmothers told me of a story that she had been told as a child by first nations traders that her family dealt with concerning the burial of Tecumseh, somewhere in South Ontario . We were told that it was a secret and I’ve managed to never blurt it out! The location does seem to be one that is now recognized as a possibility. There are two others that seem a little more far fetched but are considered absolutely true by my grandfather who I think is a tad embarrassed by one. The first is that Queen Victoria visited my ancestor who was a light house keeper at John O’Groats (that much we know is true) and was offered tea and scones. She buttered her scone with her thumb. The other is that one of my antecedents was none other than Highland Mary – mistress of Rabbie Burns. There you go – tales do go on and I will certainly pass all of those on to future generations. For the record I am 44 and come from long lines of long lived women on all sides. Thanks Kiki! EM writes, meanwhile, I am an American Southerner from the Appalachian Mountains, an eight generation Tennesseean on my dads side. My maternal grandmothers paternal grandfather was a Cherokee Indian, her name was Roda. Unfortunately, Roda died very young, only 39, and so my grandmother has no memories other, but other family members do. Recently at a family reunion, a cousin of my grandmother told my mother and myself how Roda told him as a child about her own grandparents hiding in caves to escape the Cherokee Removal, what her people called the Trail of Tears. Despite this removal to Oklahoma, there is still a large population of Cherokee still in North Carolina, where Roda was born. Cousin Les said that her grandparents had told her the story of surviving away from their farms and family, for several years, never knowing if it was safe to resume their lives. The removal was in 1838. As he is in his late 80s now, he couldn’t remember many details. One of the ironies of my family history is that my fathers people were also forced off their homelands during the creation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The government at least paid them a pittance for the farms that had been their livelihood. The park is bookended by the town an ancestor of mine founded (Gatlinburg, TN) and the Eastern Cherokee Capitol of Cherokee North Carolina (it isn’t a reservation, the Cherokee bought, and are still buying up land in the area.)’ The irrepressible KR writes in with these accounts taking us deep into the nineteenth century: One of my great great grandfathers was a blacksmith/businessman, and a farmer/ landowner well-respected in his community. One of his sons lived nearby, and often borrowed his tools but rarely returned them. One day the older man, needing one of his missing tools, sent a message to his wayward son. “Every tool that you ever have borrowed had better be returned by sundown, or I will come after them, and take the rent for them from your hide!” My aunt said she was told that uncle’s entire family, who lived on the next farm, worked all day at top speed to return the tools. “They said,” says aunt, “you should’a seen them all, running down hill and back all day! Uncle had a wife and seven children, all running, all day. Grandpa took the day off to sit on the porch to watch, and some of his other children did too. Uncle brought the last tool just before sunset. Grandpa said, ‘If that’s the last of ’em, then all of you come on in to eat, ’cause you surely worked up a good appetite.’ So they did. Uncle never failed to return a borrowed tool after that, but he never lived down the laughter of that day either.” “One morning GGgrandpa woke up and found his overalls had fallen off the footboard onto the floor. He slipped into his overalls, as usual, only to discover that one of his children’s pets, a cat, had pooped in them. Oh Lordy! He chased that cat around the house and right out the door in his longjohns with his pitchfork! Nearly wrecked the whole house! Woke up the household and scared the children half to death! Don’t know if he caught that cat, but I would bet that he did! He didn’t give up on anything easy.” This GGgrandpa lived from 1826 to 1906. I can’t give dates for the actual events, but it’s stories like these that have life and that last: because of laughter, they are retold. Another GG grandfather was a POW after the civil war. The story goes like this: GGgrandpa fought at Gettysburg and was wounded, and would have died there, but a man on the opposing side who had been an acquaintance before the war, recognized him, and picked him up and propped him against a tree. GGfather regained consciousness and they talked a bit. The man said, “I know you. I know your homeplace, I met your wife and I saw your children. I remember your horses.” GGfather said “I remember you, too.” Then both got tears in their eyes. The man kept him safe from bayonets until officers came to take him as a prisoner of war. After the war, GGgrandpa had to walk back home, already near starvation from his imprisonment hundreds of miles away. “The children were frightened by the skeletal figure coming up the drive to the house. They didn’t know their own daddy.” This latter story, told me by my aunt, was written in a local newspaper some years after the war. War records also confirm the tale. One more, told to me by my grandfather in the late 1950’s: “The folks had to fight some Indians to get to this land. But some were friendly. A few friendly Indians are buried ‘cross the road there, with your grandma’s folks, in the old graveyard. That’s what her granddaddy used to say.” The old private graveyard is still extant, though most of the stones, pioneer-carved, are no longer legible. This graveyard I once reverently visited is on land granted my ancestors in 1787, who moved there from another grant in another colony, whose parents had land in early Virginia and Maryland. The earliest definitive ancestor of my grandma’s birthname in the colonies came over from Wales and was born in 1695. This grandfather’s earliest known-for-sure ancestor can be traced to Maryland colony in 1700. Let’s see, 2012~1787 is 229 years, so I guess the story is about that old, or older, so far. I don’t know if my grandchildren will be interested to listen, or able to remember. They live far away, prefer computer games, and probably won’t ever visit that old graveyard themselves because my father’s generation sold that land when I was a teen. Recalling walking there myself, seeing and touching those old stones, keeps my grandfather’s words in place in my mind. What might anchor the stories mentally for future generations I cannot say. Keeping the land helps keep the memories, the ancestor stories, from being lost to future generations sometimes.’ Kate J writes in with this: On the handing down of family tales, I can add a bit. My late step-father was born in 1911. He told me often about one of his earliest, most vivid memories- the whole small town in upstate New York being awakened in the middle of the night with news of the Armistice. Church bells and fireworks in the middle of the night. He remembers dragging a tin can on a string down the main street and some older boys letting him shoot some fireworks. He also remembered seeing some of the early veterans’ parades. Many of the younger, shell shocked vets were quiet and pale but the old ones, dressed in blue uniforms were spry, cheerful and had long beards…. Now for Mum’s side. Just yesterday, she mentioned that her maternal grandfather was killed in the Boer War- I’m not sure which one, but I believe the first. I remember my grandmother(his daughter) talking about how he had fought the Zulus when he was a young man.The medals he received are in the care of another relative. Apparently the widow was an ill-tempered woman and the excuse made for her behavior was that she never recovered from her husband’s death. According to my mother, in this same grandmother’s home was a painting of my grandmother’s grandfather in full uniform, just before he went off to fight Napoleon. It was destroyed in the Blitz, along with the lovely home whose photos and painting I have in my dining room.Thanks KR, EM and Kiki. Beach should add something of his own here. He wrote above that his family didn’t come from Ireland. In fact they did on one side. He had thought they did not based on a conversation with his mother who actually said that she was surprised to learn her mother’s family hadn’t come from Ireland. She thought this because of a misunderstanding when she was younger. This kind of double confusion is probably more typical than the remarkable memories above.

12 Jan 2013: This great entry in the family memory catalogue comes from Terry. My family hails from Bohemia by way of Bavaria. Family lore has it that the original Stybls (what was supposedly the spelling back in the day) was a cavalry mercenary in the service of the Holy Roman Empire during the Thirty Year’s War, serving under either Tilly or Wallenstein (which is like saying that your grandfather served under Patton, if you will). There were no real winners or losers of the Thirty Year’s War, but the original Stybl came out on the bottom end, being driven from a Lutheran principality over to then-largely Catholic Bavaria. (There is legend that his under-cuirass doublet was still in the family as late as 1918 – no photos of it, however.) Once there, family memory gets a bit hazy until the early 1800s, when the by–then von Stybls were part of Bavaria’s efforts on both sides during the Revolutionary/Napoleonic Wars. It was at this point that there is the first “certain” mention of my ancestors’ cavalry pretensions – I think that the cavalry allusion during the Thirty Year’s War might have been a bit of extrapolation by distant relatives. Fast forward through the German consolidation (with a relative, another horse soldier, was commended by Kaiser Friederich III (he of the Ninety-Nine Day Rule), according to family lore – he commanded the Bavarian troops during the Franco-Prussian conflict), and on to World War I. By that point, the name was von Stibal, and my grandfather was a field grade officer commanding the engineering troops in the division in which young Adolph Hitler was serving as a lance corporal. (Grandpa Wilhelm had started with the cavalry, but moved over to engineering for some reason that remains unknown to this day.) Grandpa made it out of the Great War with a minor shell splinter wound (he spent most of his time well behind the front) and one light dose of gas. (Ironically, this was the same wound history suffered by Hitler, although Hitler’s splinter wound is widely believed to have crushed one of his testicles. Not so for Grandpa Will – his was in the back of his hand.) He and my paternal grandmother (who was quite the looker in her day, although I never saw a photo of the young her until she was quite old and dowdy) escaped from post-war Germany in the nick of time, arriving here in 1919 with some money and his musical instruments. He worked as a fireman and musician in the Midwest until his death the year before I was born. (My mother’s side came out of Kaiser Bill’s navy, where Grandpa Fred (a Prussian, through and through) was a junior (captain) engineering officer, first on the big ships but later with the end of the war U boats. Despite this resume, he was never once under fire by the enemy, missing both the early war surface actions and any operational U boat deployment. (He did see Kaiser Bill once, or so I am told.) They made it over in 1922 or so, with literally nothing but the clothes on their back. He started working as a masonry foreman in a steel foundry, but soon left to become a mason contractor, making money hand over fist during the boom 1920s. He died in the 1960s, still hating the German royal family, the Irish, and the regular officers in the Kaiser’s fleet.) My mother met my father in the mid 1930s, shortly before Father went into the US Army, where he served as a non-horse cavalryman in the divisional recon unit with an infantry division assigned to mop up on Guadalcanal. He never saw a live Japanese soldier or sailor. Later on, he was yanked from his unit and sent stateside to be retrained as a Eagle radar operator for the late war B29 units. He flew a few missions, but (again) never saw any opposition of any kind. Fast forward to the 1960s, when I was the only non-draft dodging male in the family. I managed to get an assignment (through a warrant officer in personnel who was an old family friend) to my division’s armored cavalry squadron. No horses, but the same amount of mounted fun (and maintenance headaches – horses were easy to feed and care for compared to our 1950s vintage tanks). Anyway, the only reason that I knew of all of this was that one of my aged aunts (they all seemed to be named Louise Something Or Other: Louise Ann, Louise Marie, and so forth – my father had two brothers and eight sisters) told me at a family wake for my father that he was proud that I had carried on the “family tradition” of being in the cavalry. It was only then that I learned of his early World War II escapades (I thought that he had just been in the USAAF), and of the horse background of my earlier ancestors. So, my family’s cavalry associations extended back as far as the Napoleonic era, and quite possible a century and a half or more beyond that. Not thousands of years, but give us some time… Thanks Terry!

24 Sept 2014: SKunts writes ‘After reading your post on this, I’ve decided to tell you some of the family stories I’ve been able to capture from grandparents and great-uncles. The oldest glimpse of a story comes from Ireland…several of my families emigrated during the Potato Famine, around 1849 or 1850, and the story goes that my family (McCarrick) wasn’t starving, but left because everyone around them was getting sick and they were afraid of catching something. Also, I found the town where the McCarricks came from in County Sligo, and my cousin went there and found a living relative. That relative didn’t know much about the family, but when my cousin talked to some of the older people in the area, they remembered the name McCarrick and said that they had left for England. Now, it’s true…the McCarricks went to England, some of them stayed there, and others continued on to America. They wouldn’t have known that, and my cousin didn’t even know that at the time, I only confirmed that by finding old records. Also, this ancestor (Patrick McCarrick) supposedly was a school teacher in Ireland. I don’t know if this is true or not, but the story would be from the 1840s. I had another great great grandfather, Daniel Danahy, who had six kids and was in his mid 30’s when the Civil War came around. I wondered how he avoided fighting, and an old aunt of mine told me ‘That’s because he put fly plaster on his leg and pretended it was lame!’ It turns out (from finding records) that he was drafted, but never served…so the story may be true. Also in the McCarrick family, I had a great great uncle William who left New York and went west in the 1870s. I always wondered why he did that…then, in 2005, I discovered that a 105 year old cousin of my grandmother was still alive. I travelled to California to see her, and she told me many stories that she remembered from the early 1900s, when she was a little girl. I asked her about William McCarrick and why he left home in the 1870s, and she said it was because he was dating a Protestant girl and his father Patrick didn’t like that, and they got into a fight. It was really neat getting a story from the 1870s directly from someone who knew the participants! Another great great grandfather, Paul Kuntz, came from Germany, where my grandfather told me that he was in the army, working on fortifications along the French border in 1883. His buddy told him, ‘Look at all this stuff we’re building…another war is coming soon!’ (They had just fought the French a decade earlier). So they deserted, and stowed away on a cattle boat and came to America. It turns out that Bavaria did have mandatory military service at that time, and he was of the age where he would have served when he immigrated, so he must have deserted. The story must be true. I have many other stories preserved from the late 1800s and early 1900s, but these are the earliest. It seems that it is important in my family to preserve these stories.’ Thanks!!!