The Good Friday Agreement, Teletext and an Anonymous Phone-Caller October 21, 2013

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackbackThe Good Friday Agreement – and we’ll come back to that name in a minute – was signed 10 April 1998. It was the single most important step in the winding down of the low grade civil war that had marred the province since the late 1960s and that cost over three thousand lives in the north, in the south, in Britain and on the Continent. It depended on a British premier, Tony Blair, at the height of his power, with political capital to spend, a receptive Irish administration and heroic amounts of good will and patience on the part of Northern Ireland’s two most important constitutional parties, the Ulster Unionists and the SDLP. (Beach can’t trust himself to write about the Republicans, the “Loyalists” and their wretched kalashnikovs.) Six weeks later the agreement was approved in a simultaneous vote in the six counties and to the south in the Republic, both referenda backing the agreement decisively. A new dawn beckoned. No birds sang, it rained and there was dog shit was all over the pavement but there is no question that Northern Ireland has been a more peaceful place since. Has it been a better place? Well, the jury is still out on that one, but the political framework gave both the Unionist and Nationalist communities the guarantees they needed to work together in a new and more constructive spirit. Crudely speaking the Catholic minority was given political rights and the pro-British Unionist majority had their right to self determination underwritten.

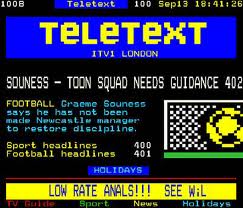

How did the Good Friday Agreement get its name? Well, d’oh, it was finalised on Good Friday. Go figure! But actually the naming process was chancy and arbitrary. The original name of the negotiations had been the Stormont Agreement, named after the part of Belfast in which the negotiations were taking place. It is, there is no question, a very Ulster name: all granite and gale force winds. But it is not exactly the stuff that terrorists kissing is made of. So who made the change? Was it Tony Blair, always a PR savvy politician? Was it one of his lieutenants, perhaps the Prince of Darkness, Peter Mandelson or Blair’s terrifying hatchet man Alastair Campbell? Or perhaps one of the Republic’s negotiator’s or one of Ulster’s more peacefully-minded politicians? Not a bit of it. It was a joint effort between an anonymous telephone caller to Britain’s teletext service and a word wizard working there. Teletext is “a means of sending text and diagrams to a properly equipped television screen by use of one of the vertical blanking interval lines that together form the dark band dividing pictures horizontally on the television screen”. Basically in pre-internet times and while the internet was gaining traction teletext was news and information pages that you could read on the television screen: see image above. A man telephoned the Teletext newsroom pointing out that ‘the Stormont Agreement’ was just not going to fit the bill: then, Judy Rees, (follow link for Judy’s version) a teletext worker, who writes on language use and metaphors listened. It was Good Friday and in a country (north and south) where religion was taken far more seriously than in the rest of the west and with that dangling ‘good’ it was such an obvious decision. Teletext ran, shortly after, an opinion poll asking ‘Do you back the Good Friday Agreement?’ The first use of the phrase. ‘Good Friday’ was, then, picked up the British and subsequently by the international media and the rest is history. Unfortunately we cannot set up parallel universes in which both the Stormont and the Good Friday agreement are put to a vote: but the chances are that Stormont would have had a rougher ride; luckily though in our version of the world Nixon shaved. Other language stories: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com