The Truth about Mussolini’s Death? October 19, 2014

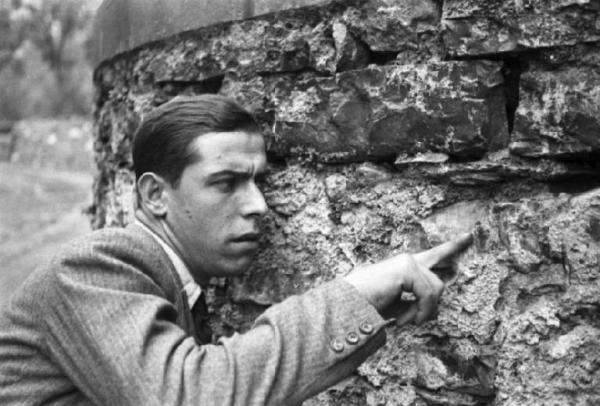

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackbackThere is no more controversial minute in Italian history. The sixty seconds took place around four o’ clock in the afternoon 28 April 1945 at Villa Belmonte (picture shows a man tracing bullet holes there). In those seconds a wrecked man, old before his time, and his much younger lover were shot dead. The man was, of course, Benito Mussolini, once one of the most powerful men in the world and the woman was Clara (Claretta) Petacci, who was then 33, and who had been, for many years, his mistress. The theories and counter theories about who killed Mussolini and his lover (and why) could and, indeed, have filled many books. However, as there has been no decent attempt to write about this in English – there have been very good studies of the history but few studies of the conspiracy theories in that language – we include here the cream of what the Italians call dietrologia. These are listed not to further the cause of knowledge, but more as a tribute to human ingenuity, in much the same way as a list of candidates for Jack the Ripper or locations of Atlantis (Bolivia anyone) are entertaining to the casual reader. Beach then offers the only reliable account, translated for the first time into English.

Three Communists: The conventional version, often sneeringly called the Vulgate by Italians, claims that three communist partisans carried out the execution of both Mussolini and Petacci. The problem is that the three partisans disagree among themselves and also, more worryingly with their own earlier accounts. For example, did Petacci die because she interposed herself between Mussolini and the guns or did she die because she was deliberately targeted? Well, it depends on who you ask and at what date you ask! The main argument is over which of the three pulled the trigger.

The British Did It: This is the James Bond syndrome, the idea that the British have both the will and the power to run the world as if they were playing battleships in 1890. (Would that it were so…) The British in this case had a guilty secret. Churchill had been writing on the hush hush to Mussolini and now the war was over these letters and the witness, Mussolini, would have to be got rid of. Either the Brits did it themselves, then, or they paid off some henchmen to do it. Note that there is satisfactory proof for correspondence between Churchill and Mussolini before the war. There is no evidence for such correspondence once the war had begun.

Blame Longo: Luigi Longo was an important communist ‘commisar’ in northern Italy who would, many years later, become leader of the single most important Communist party outside the Soviet bloc and China, the Italian PC. There have been suggestions that Longo himself shot the Duce, which doubtless he would have gladly done, only, and this is awkward, he was photographed in a parade at Milan at about the same time. A double perhaps? Or the early killing theory (see below). Those tricky reds…

Mussolini Did It: This one is particularly incoherent. Basically Mussolini had secreted a poison capsule under his tooth and had bit this at an opportune moment. He was then shot in a coma with a very much living Petacci. But why cover any of this up?!

Early Killing: The Duce had no food in his stomach (so the mortuary doctor claimed), this would suggest that the Duce had been killed early in the morning. Theories here crowd in on each other, but there is the possibility that Mussolini and Petacci were killed in the house where they had been placed under arrest rather than against the wall of a nearby villa. The shooting did take place at the villa, but that was, so some claim, a pretend shooting of corpses. Were the British or Longo responsible?!

Mussolini Didn’t Die: actually and rather disappointedly no one has suggested that Mussolini escaped to Antarctica, Mars or Argentina. But why not? A gap in the conspiracy market… Or perhaps Muss in the end just wasn’t scary enough to keep for our nightmares.

Other duce theories: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

And the truth? As noted above there are great uncertainties about the Vulgate version. However, there is also a general underlying consistency. The communist partisan who spoke most about the killing, over the years, was Audisio, a compulsive liar: a fact helped along by the PCI’s own use of tall stories. However, one of the three had, instead, the makings, of an outstanding witness. This was Aldo Lampredi. Lampredi, in fact, refused to speak to the press (always a good sign), but he spontaneously wrote a memo for the Communist party in 1972 (the year before his death) as a secret historical record, which was preserved in the PC’s archives until in 1996 Unità (Italy’s communist newspaper) published said memo for its readers: it might be noted that Unità had done more than any other part of the media to obscure the truth about what had happened to Mussolini so the 1996 publications might stand as a kind of penance. Lampredi’s words have been attacked by some: for example, he gets details of local geography wrong. But as a private document by a witness, given to the PCI with no thought of publication, it recommends itself to posterity. It also, horrible phrase, ‘rings true’. Mussolini’s catatonic state, Petacci’s hysterical courage, and the Duce’s final gesture with his coat. There are many apparently irrelevant details here, often where Lampredi is trying to clear up ambiguities and lies alleged by other witnesses. To the best of Beach’s knowledge this is the first time this central passage has been translated into English: it has often though been summarised. Here you see the last ten minutes of Mussolini’s life.

After the meeting of the twenty-second command, while Pedro got the fascist leaders outside Dongo brought there [so they could be executed], we sorted out how we would shoot Mussolini and Petacci. We left, Audisio, I and Moretti, with a car and a driver requisitioned on the spot. We got to the house of De Maria [where Mussolini and Petacci were being held], we went up the stairs and in front of the bedroom door we found two partisan guards, Lino and Sandrino. We went in and I remember vividly how Mussolini stood to the right, close to the door, while Petacci was stretched out on the bed. I must say that at that moment, all my senses and my eyes were concentrated on Mussolini. I was greatly struck by just how miserable he looked. Perhaps I was still influenced by the strong image of Fascist propaganda and I had expected to find a vigorous, energetic man. Instead, before was an old man with white hair, short, with a forelorn look. He kept his forearms lifted upwards and in each hand he had a glass case which we took. I don’t even know why we took the glass cases (we gave them later to the Central Command). My attention was fixed on Mussolini, and I didn’t take in what was happening round about. I remember the question of the knickers of Petacci [Petacci didn’t have time to put them on], but I didn’t hear the words that Audisio claimed to have said to Mussolini and his response. On the other hand, I didn’t see that there was any need to calm Mussolini, who, as far as I could see, was as good as finished there, likewise I couldn’t see what offers [?] he could make in those conditions in which he found himself. We went down to the car and told the prisoners to get in, and I sat next to the driver. Audisio put himself on the back mudguard and perhaps Moretti went on the other. The trip was brief and quickly we arrived at the gate of Villa Belmonete where we had decided to execute Mussolin. I bent towards him and said some words the sense of which were ‘whoever would have guessed when you persecuted communists that one day they would make you pay for what you did.’ Mussolini said nothing, Petacci gave me a questioning look for which she must have found no consolation in my eyes. Mussolini and Petacci were made to get out and put against the wall, close to the gate. She was to the right of Mussolini. Audisio did not read any sentence, perhaps he said some words, but I can’t be sure. He aimed the machine gun, but the gun didn’t work. I was on the right and I took a pistol that I had on in the pocket of my jacket, and I pulled the trigger but nothing happened, it had blocked. Then we called Moretti on our left, towards the piazza with the washing place. Audisio took his machine gun and shot at both. All this happened in an incredibly short time: one or two minutes in which Mussolini remained still, stunned, while Petacci shouted that we could not shoot him and she went up to him as if she wanted to protect him with her body. It was perhaps her behaviour that forced Mussolini into a reaction and standing straight and opening his eyes wide and pulling his anorak apart he shouted ‘aim at my heart!’

Dopo la riunione col Comando della 52ma Brigata, mentre Pedro provvedeva a trasportare a Dongo i gerarchi che erano altrove, stabilimmo di procedere alla fucilazione di Mussolini e della Petacci. Partimmo, Audisio io e Moretti, con una macchina e l’autista requisiti sul posto. Arrivammo alla casa De Maria, salimmo le scale e davanti alla porta della stanza dove stavano Mussolini e la Petacci trovammo di guardia i due partigiani Lino e Sandrino.Entrammo e ricordo con grande vivezza che alla mia destra, vicino alla porta, in piedi, stava Mussolini mentre la Petacci era distesa sul letto. Debbo dire che da quel momento, i miei occhi, tutte le mie facoltà, furono concentrate su Mussolini. Rimasi profondamente colpito dall’aspetto miserevole che egli presentava. Forse ero ancora influenzato dall’immagine apologetica fattane dalla propaganda fascista e mi aspettavo di trovare un uomo vigoroso, energico, invece avevo davanti a me un vecchietto bianco di capelli, basso di statura, con un’aria svanita. Teneva gli avambracci leggermente alzati e in ciascuna mano aveva un ascuccio di occhiali che immediatamente gli presi: non so nemmeno perchè, (li consegnai poi al Comando Generale). La mia attenzione concentrata su di lui, non mi ha consentito di seguire tutto quello che accadeva d’intorno. Ricordo il riferimento alle mutandine della Petacci, ma non ho sentito le parole che Audisio dice di aver detto a Mussolini e la risposta di Lui. D’altra parte non vedo che bisogno c’era di tranquillizzare Mussolini che, in ogni evenienza, poteva esser finito sul posto; come pure non vedo quali promesse egli poteva fare nelle condizioni in cui si trovava. Scendemmo a piedi fino alla macchina, vi facemmo salire i prigionieri, ed io presi posto vicino all’autista. Audisio si pose sul parafango anteriore e forse, Moretti sull’altro. Il tragitto era breve e presto arrivammo al cancello della Villa Belmonte dove avevamo stabilito di procedere all’esecuzione. Mentre Audisio si accertava che non ci fossero persone in vista e forse, aspettando l’arrivo di Lino e Sandrino, che invece arrivarono dopo la fucilazione, io mi avvicinai alla portiera dalla parte dove sedeva Mussolini, mi chinai verso di lui e gli dissi alcune frasi il cui senso era questo: ‘chi avrebbe detto che tu, tanto hai perseguitato i comunisti, avresti dovuto regolare i conti con loro?’ Mussolini non disse nulla, la Petacci mi rivolse un lungo sguardo interrogativo al quale essa deve aver trovato fredda risposta nei miei occhi. Mussolini e la Petacci furono fatti scendere dalla macchina e fatti mettere al muro, vicino al cancello. Lei alla destra di lui. Audisio non lesse alcuna sentenza, forse disse qualche parola, ma non ne sono sicuro. Puntò il mitra, ma l’arma non funzionò. Io che stavo alla sua destra, presi la pistola che avevo nella tasca del soprabito, premetti il grilletto, ma inutilmente: la pistola si era inceppata. Allora chiamammo Moretti, che si trovava alla nostra sinistra, verso la piazza col lavatoio, Audisio prese il suo mitra e sparò ad ambedue. Tutto questo avvenne in brevissimo tempo: uno due minuti durante i quali Mussolini restò immobile, inebetito, mentre la Petacci gridava che non potevamo fucilarlo e si agitava vicino a lui quasi volesse proteggerlo con la sua persona. Fu forse il comportamento della donna, così in contrasto con il proprio, che all’ultimo momento spinse Mussolini ad avere un sussulto, a raddrizzarsi, e sgranando gli occhi ed aprendo il bavero del pastrano, ad esclamare:’Mirate al cuore!’. (Mi sembrano pìù vere queste parole che quelle riferite dall’autista Geninazza ‘Sparami al petto’)