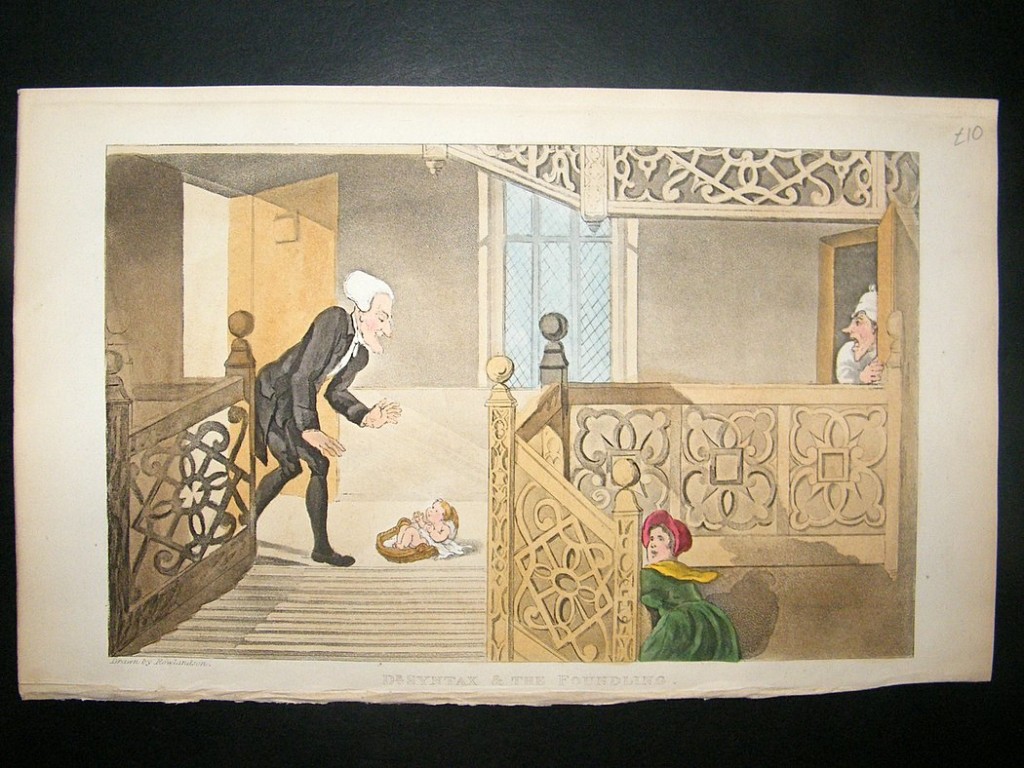

Foundling Names August 8, 2015

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary, Modern , trackbackWe recently offered a post on the names given to bastard children. Here is a related and far nicer post on the names given to foundlings, who seem to have been treated, perhaps strangely, with rather more respect by society. Today, if an anonymous individual turns up, he is, in the US, referred to as John (or for a woman Jane) Doe. In Britain, at least in the seventeenth century, there was the tradition of using the place in which a baby was found for the surname: the Christian name was usually taken from a godparent. These few examples give some flavor and appeared in the London Parish of All-Hallows, Barking in London and are taken from Bardsey (1897):

‘A child, out of Priest’s Alley, christened Thomas Barkin.’

‘Christened a child out of Seething Lane, named Charles Parish.’

And the lovely:

‘A child found in Mark Lane, and christened Mark Lane.’

In another London parish names were also given with attention to locality. So we have:

‘1611, May 11. Harbotles Harte, a poor childe found at Hart’s dore in Fewter Lane, bapt.’ Foundlings were sometimes left at their father’s door. Perhaps Hart was, indeed, the father?

‘1618, Jan 18. Mary Porch, a foundling, baptised.’ Presumably Mary was left in the [church?] porch?

A particularly moving example comes from the early seventeenth century.

Sept. 1, 1611. Job-rakt-out-of-the-asshes, being borne the last of August in the lane going to Sir John Spencer’s back-gate, and there laide in a heape of seacole asshes, was baptized the first day of September following, and dyed the next day after.

The reference to this bizarre name is explained by Job 2/8 where the prophet sits among the ashes.

Another boy was called surnamed Outecaste, a name that needs no explanation and was beautifully combined with the Christian name Moses (Bletchindon Parish Register).

This tradition carried on late into the nineteenth century: for example in 1894, ‘William Euston, a child found in a box in a railway carriage at Euston Station [in London].’

However, this sensible rule did not always operate. In 1861 at Cashel a baby left at a workhouse was named not Cashel but Kettledrum. After, er, the winner of the Derby!

In America places were generally used too for foundlings, though sometimes alternatives were enjoyed here too. For example, one child rescued from a shipwreck off the coast of New Jersey was taken in by a man called Fish who called the baby Preserved. At least this is the story that the normally reliable Bardsey gives, though Beach has his suspicions.

The naming tradition for foundlings carried on, with rather more seriousness, into the twentieth century (and perhaps still subsides as a principle in English law to this day?):

One newspaper from 1935 describes a baby boy with a Roman Catholic symbol and a pound note pinned to his front found at St Anthony’s Home, Aldershot. He was given the name Anthony, of course, rather more inexplicably Bradbury: and the local council (in the English Protestant heartlands) insisted that he be brought up a Catholic.

Other foundling naming traditions: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com