Arab Embassy to Dark Age Scandinavia July 19, 2016

Author: Beach Combing | in : Medieval , trackback

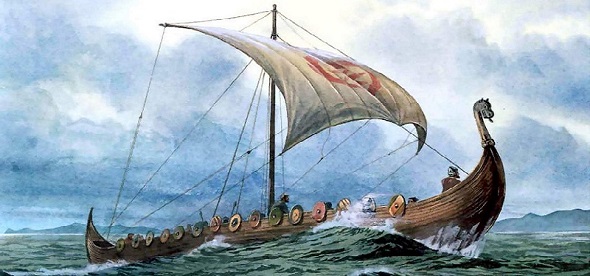

The Vikings were attacking everyone in the ninth-century and this included the Arabs of southern Spain. After their most famous raid, in 844, when Seville was memorably captured by those northern psychos, the Emirate of Seville did something quite extraordinary. He decided to send an embassy to the Viking homelands to buy them off. This was misguided for all kinds of reasons: not least because he was simply advertising the two things that most interested the Vikings, wealth and weakness. But an account of the voyage of the Arab ambassador survives (Ibn Dihyah). If it is genuine, and it first appears in the thirteenth century, then it is a remarkable memory of a Muslim in Dark Age Scandinavia. The ambassador sent north was one Yahya al-Ghazal, a poet, who had spent part of his life in Iraq:

When they came opposite the great promontory which enters the sea, the boundary of Spain in the extreme west, i.e. the mountain known as Aluwiyah [Finis Terrae in Galicia?], the sea swelled up against them and a violent storm descended upon them.’ Yahya al-Ghazal recited verses appropriate to their situation. [verses about fury of the storm] After the storm abated, they reached their goal, the land of the Norsemen.

This jump from Corunna [?] to the land of the Norsemen has been taken to suggest that the ‘king of the Norsemen’, a fairly meaningless phrase in the anarchic Viking age, was based in Ireland. It is true though that the meeting between Yahya al-Ghazal and the Viking king takes place on an ‘island’. The Vikings in question were allegedly Christian which is surprising at this date, anywhere. Here is an anecdote from the visit.

After two days the king summoned them before him, and Yahya al-Ghazal explained that he would not be made to kneel to him and that he and his companions would not do anything contrary to their ways. The king agreed. However, when they visited him, he sat before them in magnificent guise, and had an entrance, through which he was, perforce, approached, so low that one could only enter kneeling. When al-Ghazal came to the entrance, he sat down, stretched his legs, and dragged himself through on his bottom. And when he had come through the doorway, he stood up.

Yahya al-Ghazal then invokes Allah: exciting to think of a Viking getting banged over the head with a Saudi Arabian sky god in the 800s. Yahya afterwards, developed a particularly intense relationship with the Viking queen, Nud, and actually declaims a line of poetry: ‘I am in love with a Viking woman.’

This is all extraordinary, but again is it actually a genuine record of a genuine trip? Yahya al-Ghazal was a ‘character’ and a series of anecdotes have been written about him, not all of which sound true. Most worryingly, there is a record of an embassy to Constantinople in which the Emperor tries to trick Yahya al-Ghazal into bowing by presenting him with a low entrance and then includes a flirtation with the Empress…. Sound familiar?

Other long distance embassies in antiquity or the Middle Ages: drbeachcombing at yahoo dot com

Bruce T, 31 July 2016: ‘Al Ghazal and the tales around him seem more like Mahgrebi Sinbad stories than they do anything else. His time occurs just after the always strange, Abulafia, “The Mad Arab” who supposedly literally fell apart in the streets of Tunis after dabbling in the dark arts. I think they just liked wild tales out on the edge of the Muslim world.

Ashley, 31 July 2016: Quite right as I understand it. Christian vikings c 844 is a bit much to believe. The tale is surely commingled/conflated with something closer to the date of the 13th c retelling when Jesus had been official for 200 years and the viking kings had come and gone Harald to Harald.

Cheese writes, 31 July 2016, ‘I had never heard of this source. Must be where Michael Crichton got the idea for his book, “Eaters of the Dead”? I read that when I was much younger, and was embarrassingly taken in by the impressive-looking footnotes until I got a surprising way through the book. If you haven’t read this, you might want to take a peek (disregard the movie based on same, which was not a bad movie as movies go, but of course, nothing like the book).’