Gaelic-Speaking Russians in 1914 September 9, 2016

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackback

One of the most interesting myths to come out of First World War Britain was the tall tale of the Russian soldiers with ‘snow on their boots’. The story, which emerged as the war began in Aug and Sep 1914, was that thousands of Russian soldiers had been rushed to the UK. They were there to get at the Germans from the west. These Russians were typically spotted on trains – though there was one landowner who claimed to have watched 150,000 Cossacks riding across his estate. They were recognized by their inability to speak English and their strange foreign ways. Questions were asked in the House of Commons. Reports were written for British intelligence. And rumours, of course, did the rounds in the newspapers. The story itself is quite well known, but where on earth did it come from?

Well, urban legends don’t need seeds. They can grow from nothing. Certainly they all too often to return to nothing. There was a need. The British needed hope as the war began and before archers fantastically appeared at Mons. The Russians were eastern promise (the most potent direction in the European imagination) and there was the widely held belief that the war between Russia and Germany would take some time to get going because of poor transport infrastructure in what is today Poland. The Germans’ Schlieffen plan was based around this very notion. But was there a more proximate cause for the legend?

There has long been an interesting minority opinion that the Russian soldiers were actually Scots soldiers coming south. This seems to have first been suggested in February 1915. By 1978 it has become simple fact: though is it not just an urban legend within an urban legend?

This started the rumour that a force of Russians had landed in the north of Scotland, and were on their way south. The fantastic story, which spread like wildfire, had some foundation, for it fitted in remarkably well with the movements of the Highland Brigade. More than a dozen troop trains had passed through Newcastle and York, travelling in succession during the hours of darkness. Many of the men on board were reported to speak a foreign language, wear curious headgear, and be uncommunicative and shy in manner. When asked from whence they came by benevolent ladies staffing a canteen on York platform, they could only murmur, ‘Roscha’ (Ross-shire) [in Scotland].

So there… Beach always presumed that this was nonsense. It is true that some members of the Highland Brigade will have spoken Gaelic and a small number will have spoken Gaelic as their first language: though presumably all understood English. However, he now feels like rowing back a little. He ran across this passage in Defending Albion by Mitchinson (57):

The Highland Division, part of the Central Force’s First Army, assembled at Perth, Dublane and Inverness before moving to its war station at Bedford. The arrival of Gaelic-speakers caused the local residents not only language difficulties, but also wreaked havoc with the town’s sewage disposal system.

There is actually a good deal of material on the 12,000 Highlanders who made Bedford their home from 4 August 1914, including on this excellent website. The author confirms that Gaelic was spoken.

A large number of the soldiers, particularly those of the Cameron Highlanders, spoke Gaelic as their first language. It is probably not too surprising that the Highlanders were perceived as being somewhat wild and uncouth by some of the more genteel members of local society.

Again it is surely a tall order to believe that even mother-tongue Gaelic speakers did not know English by 1914. But Beach has come across Gaelic speakers from Ireland who had no English between the wars so he will reserve judgment. The isolation of some of the Highlanders is also demonstrated by the fact that 49 died of a measles’ epidemic in barracks at Bedford and several hundred became ill. Perhaps not Gaelic but thick accents were the cause of the confusion with ‘Russians’? Thick southern English accents and thick Scottish accents could have led to all kinds of misunderstandings when mixed together in conversation.

So what about it. Should the Highlanders be credited with starting the Russian rumour? Drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

The best account known to Beach of the Russians in Britain in 1914 is that wonderful book, Hayward, Myths and Legends of the First World War.

9 Sep 2016 Lewis writes: ‘Donald MacAulay’s book, ‘The Celtic Languages’, would suggest that in 1911 there were around 8400 monoglot speakers of Gaelic in Scotland. This figure rises by 1921 while the number of bilinguals falls. Perhaps men were more likely to be bilingual? This would explain the steep decline in bilinguals during that time. The last generation of monoglot Gaels appears to have passed away in the 1970s. What is easy to forget is that, while they would have received an English language education, many of these men would have been much more comfortable speaking Gaelic. Not only would they have heard this language in the cradle, but they would have spoken it at home, sung in it, chatted to their friends in it and related to the landscape through it. That would explain any “shy” behaviour when addressed in English. I rather doubt that men with no English would have been recruited, but how much English did the Indians fighting on the Western Front know? How good was the German of the Czech ploughmen and Hungarian shepherds in Franz-Joseph’s army?’

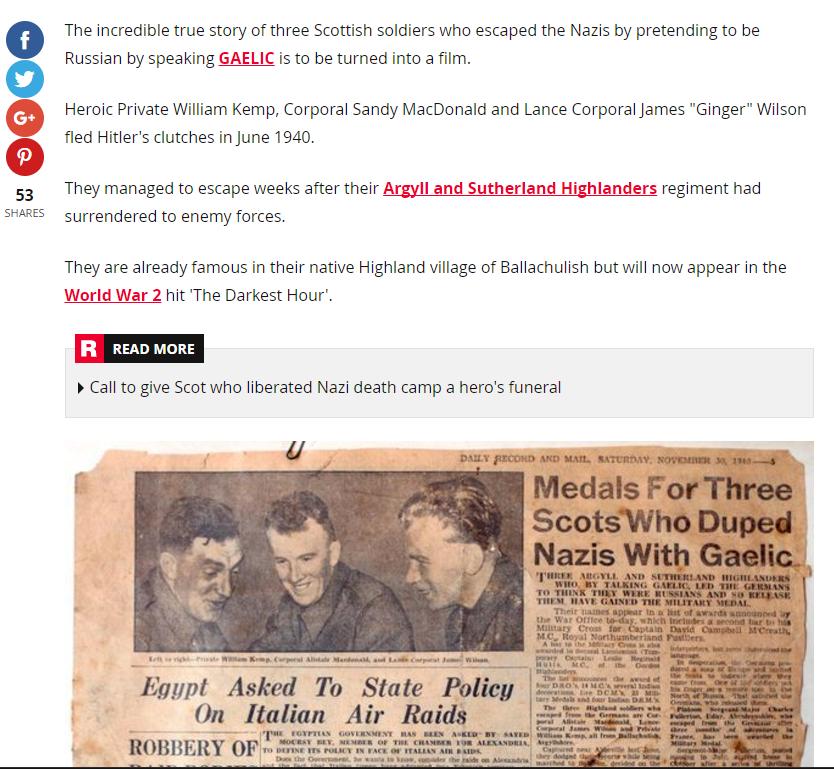

18 Jun 2017: RVU sends in this article ‘New film to tell true story of how Scottish soldiers escaped Nazis by speaking Gaelic and pretending they were Russian. William Kemp, Sandy MacDonald and James “Ginger” Wilson escaped in 1940 after convincing their captors they were from the Soviet Union.’