Kitchener Survives: Friend of a Friend May 15, 2017

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackbackOne of the great British catastrophes of the Great War was the death of Lord Kitchener on the HMS Hampshire in the North Sea 5 June 1916, not a month before the Battle of the Somme began. Kitchener, famous as British Secretary of War was a ruthless and effective warleader and understandably British public opinion had difficulties coming to terms with his sudden drowning: the Hampshire ran into a German mine and went down with most hands; just twelve men were rescued from over seven hundred. In the wake of this tragedy two forms of conspiracy theory reared up. The first, that need not concern us here, was that it wasn’t a German mine: it was a Boer or an IRA or a German bomb on the vessel that did for the British ship. The second was the much stranger idea that Kitchener’s death had been faked and that the good English Lord survived the wreck. There were various permutations of this theory, but the most common was that the Germans had picked up Kitchener from the water and taken him to prison in Germany where he was being held in secret. By the summer of 1916 Mrs Parker, the sister of Kitchener had come around to believing this. Beach was most interested though by this report from late July 1917 that demonstrates there was a more general tale doing the rounds.

[The conspiracy theory] has usually taken the form of a story of a survivor of the Hampshire, now a prisoner in Germany, who writes home to his friends that Lord Kitchener was also saved, and is in enemy hands. We have repeatedly tried to track down this story, but the chain of evidence has always broken before it reached the persons who actually received the letter. We unhesitatingly affirm our belief that no such letter exists.

Lovers or urban legends will recognize the classic foaf (friend of a friend) trope. Jim told me that he has a mate who had got a letter from a friend of his who is resident in one of the Kaiser’s prisons… In the words of another newspaper (Liv Daily Post):

Most of these take the form of a report that somebody knows somebody who knows somebody whose wife’s sister’s husband wrote to someone else that Lord Kitchener was a prisoner at the camp where he was interned.

It would be interesting to know more about how the legend worked. The Hampshire was lost just off Orkney, not a place that the German navy could safely visit. (One journalist makes the very good point that prisoners from the HMS Hampshire might have got confused with prisoners from the Hampshires, a regiment,Liv DP 28 May 1917) Had a submarine come to the surface at just the right time and pulled a man in a field marshal’s uniform from out of the brine? The story had clearly been enjoyed already by Dec 1916.

A charwoman told her employer that at a house where she worked the lady was always in mourning for a son who went down in Hampshire. One day the charwoman found the lady dressed in white, and the lady told her that had just received letter from her son who was a prisoner Germany, who had been saved from the wreck, ‘and you would be much surprised to hear who is with me here.’ Inquiries were made and the charwoman admitted that there was no such lady, but that the story came from some third party who could not be traced. She had added some of the circumstances herself. (Derby 15 Dec 1916)

Wonder if she lost her job.

A business was told by the manageress of a factory connected with his business that one of the girls of the factory had had a letter from her brother, who had been on the Hampshire, to say that he was a prisoner in Germany, and Lord Kitchener was with him. The girl, she said, had taken the letter to the War Office. Again it was found that the origin [of this story] was that one girl had heard some such story from the untraceable relative of married sister. (Derby 15 Dec 1916)

And was their possibly a real letter that started all this: the Star 2 Jun.

This sister of an officer admittedly a prisoner has received a postcard from him, in which he observes: ‘I wish I could tell you who is a prisoner in the next room to me.’ Examined under a magnifying glass, the card in one corner has a minute K.

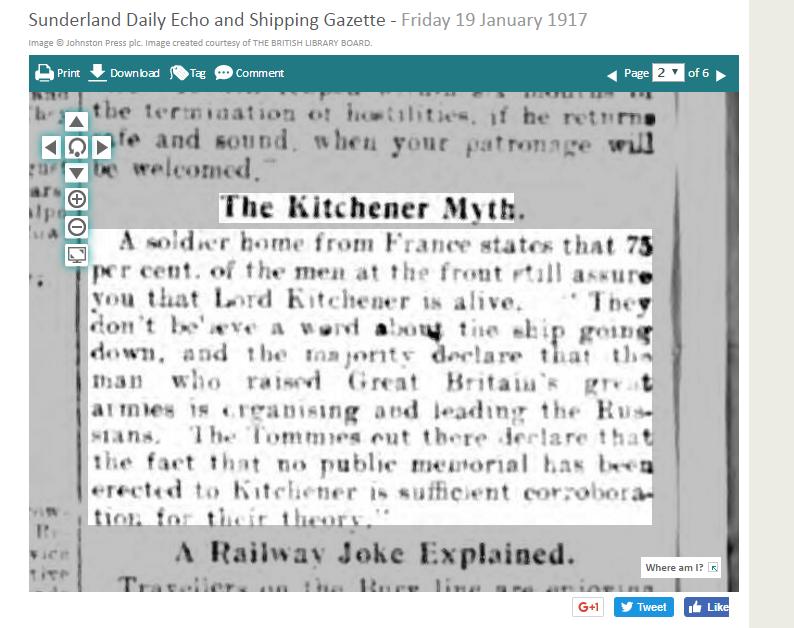

Note that another version was popular on the front by Jan 1917.

The Star 2 Jun also gives another rumour namely: ‘that the survivors of the H.M.S. Hampshire have never been allowed to return to their families, but are interned in Scotland.’

One other theory, which is rather more credible (all is relative) is that Kitchener was picked up by a neutral boat and taken to the other side of the world. Beach’s fave though is from a lady gifted with second sight. She claimed that Kitchener had turned up in Russia but had been kidnapped by the Tsarina, a notorious Germany sympathiser. Liv DP 28 May 1917

Other Kitchener survival stories: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

These years added together from left to right give the following numbers:

1896-24-6. Opening of Egyptian campaign.

1897-25-7. Atbara and Omdurman.

1898-26-8. Rest from Labour–Honoured by Nation.

19I4-15-6. Opening of the Great War.

19I5-16-7. Creation of Britain’s Army of 4,000,000.

1916-17-8. Rest from Labour and death–Honoured by Nation.

“Tell me what you like,” he said, that morning of July 21st, 1894, “as long as the end is some distance off.” And yet, when I pointed out to him that the 6 and 7 and the 8 were the most important numbers of his life, as quickly as the late King Edward worked out from my figures that 69 was likely to be the end of his life, and joked with me and others about it afterwards–so Kitchener, with perhaps the same mysterious flash of intuition, ran his pencil down the figures I had just worked out to the date of 1916 which was indicated as ” Rest from Labour.” “That then is perhaps ‘The End,’ ” he said. “Strange, isn’t it?” he laughed. “But is there any indication of the kind of death it is likely to be?”

“Yes,” I said. “There are certainly indications, but not at all perhaps the kind of ‘ end ‘ that one would be likely to imagine would happen to you.”

I then showed him in as few words as possible, that having been born on June 16th, 1850, he was in the First House of Air, in the Sign of Gemini, entering into the First House of Water, the Sign of Cancer, also House of the Moon and detriment of Saturn. Taking these indications, together with the kabalistic interpretation of the numbers governing his life, the fatal year would be his 66th year, about June, and the death would be by water, probably caused by storm (Air) or disaster at sea (Water), with the attendant chance of some form of capture by an enemy and an exile from which he would never recover. “Thanks,” he laughed. “I prefer the first proposition.”

“Yet,” he added, I must admit that what you tell me about danger at sea makes a serious impression on my mind and I want you to note down among your queer theories, but do not say anything about it unless if some day you hear of my being drowned–that I made myself a good swimmer and I believe I am a fairly good one–for no other reason but that when I first visited you as quite an unknown man many years ago, you told me that water would be my greatest danger. You have now confirmed what you told me then and have even given me the likely date of the danger.

“Good-bye,” he said, “I won’t forget, and as of course you believe in thought transference and that sort of thing, who knows if I won’t send you some sign, if it should happen that water claims me at the last.”

Confessions: Memoirs of a Modern Seer, Cheiro 98-99

Cheiro believed he had gotten a sign the night of the disaster when a shield painted with the British coat of arms that hung in his house fell and broke in half. He also says that he received a letter from a Boer woman who said that she and her family had been burned out by Kitchener’s troops and imprisoned in a concentration camp. She swore revenge and claimed that her son, who worked loading ships at Scapa Flow, had placed an infernal machine on the Hampshire in the disguise of stores. The son had since died of consumption and she, gloating over her revenge, was on her way back to South Africa.