Imaginary Kingdoms September 3, 2013

Author: Beach Combing | in : Actualite, Contemporary, Modern , trackbackBeach has often featured forgotten kingdoms on this blog. But what about imaginary kingdoms? There seem, in the lives of some children, to be a moment when the young create a magical world for themselves that takes on a permanent form: perhaps a more (or less?) elaborate version of the invisible friend? These are often shared with brothers or sisters, in fact, close sibling relations seem often to be a factor in the creation of these weird little spaces. Beach himself enjoyed an imaginary world from about the age of 9 to his mid teens: he didn’t share it with his brother because his brother was too busy playing soccer. But he can say that these things are alarmingly potent and sometimes they still intrude into day to day life, almost as memories, decades on. There was a burning cross…

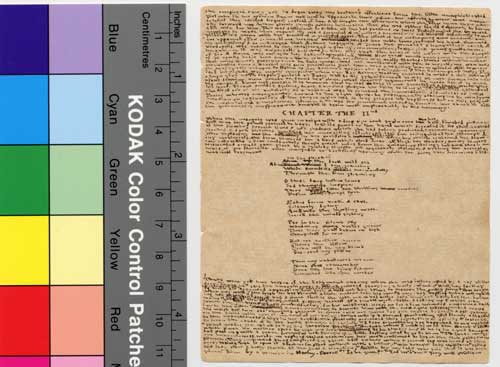

Beach wants to try and work up a list here of famous imaginary kingdoms; that is worlds invented and enjoyed by children who later became famous men and women. Perhaps the most celebrated case of all is Gondal: the world shared by Emily and Anne Bronte. They were both in their late teens when the island of Gondal miraculously appeared in the South Pacific, so we have something that is half way between a child’s game and a literary conceit. But they had form: as children they had shared with their other siblings, the tiresome Charlotte and drunk-to-be Branwell an imagined reality called Angria, which also tipped into their teenage years. There are some Angrian stories that survive and that can only be read with a magnifying glass (image above): apparently Angria was dominated by the Duke of Wellington so at least the rule of law operated there.

Had the West Riding moors sent the Bronte siblings to madness and beyond? Well, very probably, but this is not an isolated case by any means among children who later become writers. C.S.Lewis and his brother used to play in Animal Land: some of CSL Animal Land stories have actually been published. However, Beach’s favourite example is Katharine Briggs, English novelist and folklorist, who shared an imaginary country with her two sisters, employing maps of Holland and Denmark. There Charlie and Earnest, two princes, had various, rather feminine adventures. Their great enemies were the Colour Strips, a group of nihilist terrorists who killed the boys’ guardian King Robert. In the last year of her life, as an elderly lady, KB was asked about ‘the game of Eric’ as she and her sisters had known it and ‘was sparkling and enthusiastic, and … used a child’s language to describe the episodes and developments.’

This longevity is remarkable but not unprecedented. English author, Eleanor Farjeon (obit 1965) inhabited, in her late Victorian childhood, a game world called TAR: ‘I know [wrote EJ] of no case in which the game of two was continued for more than 20 years with increasing richness.’ In fact, dear EF was still writing to to her brother Harry about TAR while at university! It was clearly a way in which they communicated with each other. Another case is the strange Hartley Coleridge, son of Sam, who kept his Ejuxria up and running till the year he passed: did he take leave of the Ejuxurians on his death bed? Then, there is Tolkien’s Middle Earth which apparently began as a kind of philogical wet dream in late puberty. Or what about the extraordinary Henry Darger… Wow.

Reading about these places is a little like peeking into someone’s dream. It is clearly very important to them, but a little strange, and dare Beach say, boring for everyone else. We just can’t makes sense of the hieroglyphs and sometimes, just sometimes, it can also be creepy. Any other of these imaginary worlds? drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com What function do they serve? Are there any pre-nineteenth century examples?

3 Sept 2013: Southern Man is in a censorious mood: ‘Beach, the technical term is parocosm. I refer you and not for the first time to Wikipedia. Also what’s the difference in the end between a child’s imaginary world and a novelist creating a story?’ The Count starts with a similar point: ‘Now there’s a big subject! I shall leave aside the many, many literary examples, since I’m not quite sure what your criteria are supposed to be, and merely mention the unbelievably detailed Ummo Hoax. It has never been conclusively determined who was responsible, or what the point of it all was. One explanation is that, in the same way that writers such as Stanislav Lem got away with being surprisingly satirical of the Soviet Union even though they were writing behind the Iron Curtain by disguising it as science fiction, the more far-out the better, the purpose of the whole affair was to get Spaniards under Franco’s rule talking about wacky made-up aliens who just happened to have a political system which was pretty far to the left. Though if this is really what happened, it’s odd that they never admitted it. And it’s very doubtful whether the one man who has admitted it could have accomplished such a massive task alone and still had time to have any kind of life. The hoax was astonishingly detailed, and included reams of scientific text that was surprisingly erudite (though not superhumanly so), staggering amounts of detail concerning all aspects of life on the planet Ummo, quite good fake photographs of flying saucers marked with the distinctive Ummite logo (a sort of bendy H apparently derived from the astrological symbol for Uranus), and samples of mysterious substances which actually fooled a thoroughly reputable Spanish laboratory into saying that they couldn’t have been manufactured on Earth. In fact, they were obtained from a small firm in America which manufactured tiny quantities of otherwise unobtainable substances for very specific scientific purposes. So as hoaxes go, it was incredibly thorough! It even inspired a low-budget Spanish sci-fi movie called The Man From Ummo that so obviously ripped off The Day The Earth Stood Still that it even starred Michael Rennie. Possibly the best explanation, which is still pretty far-fetched, is that a group of people seriously tried to put the concept proposed in a famous short story by Borges into practice. The similarities are striking, right down to their attempts to manufacture the nearest thing to physically impossible objects that they possibly could. Who knows?’ NN writes: Don’t forget E.R. Eddison! As a child he created the world and characters that ultimately became “The Work Ouroboros,” which Tolkien praised as one of the best fantasy novels of all time.’ Thanks to NN, Southern Man and the Count! Hope we’ve gone one up on Wikipedia here.

4/ Sept 2013: An old friend of this blog, Ray G writes in: Regarding imaginary kingdoms: one that immediately springs to mind is Borovnia, the shared fantasy kingdom of Pauline Parker and Juliet Holme. Then EC Not quite what you’re after as it seems to have had its origin in outright mental illness rather than childish fantasy but the strange case of “Kirk Allen” should be mentioned. He spent years creating a fantasy world in prodigious detail before being cured by a therapist, who later wrote about the case in his book The Fifty-Minute Hour. Jacques Vallee also mentions Kirk Allen in his book Revelations, as evidence that the large quantity of UMMO material was no indication of extraterrestrial origin. But I digress. Thanks to Ray G and EC!