Phoenician Sun God in Eighteenth-Century Ireland? March 2, 2017

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient, Modern , trackbackIt is the most extraordinary inscription. This mill-stone rock, which once stood on the top of Tory Hill in County Kilkenny in Ireland, has been taken as proof of Carthaginian contact and settlement or at least trade with Ireland in antiquity. The words clearly read (give or take some distorted letters) Beli Dinose, a reference to the Carthaginian god Bel or Baal Dionysus. Just think that Phoenicians, in the early centuries B.C. brought their nasty child-killing faith to the green hills of Ireland! Only of course they didn’t… At least not on this evidence. The stone celebrating ‘the lordly one’ actually has a rather different origin.

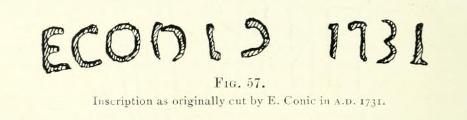

In 1731 one Edmond Conic, a mason, found himself on top of Tory Hill as he had been sent to prepare a mill stone there. His work colleagues did not turn up and because he was bored he began to carve his name into a large rock. They must have been very late because he managed to finish ‘E. Conic 1731’ before giving up and going home. You may notice that the final ‘c’ was reversed. E. Conic was not, something quite normal in Ireland at this date, fully literate.

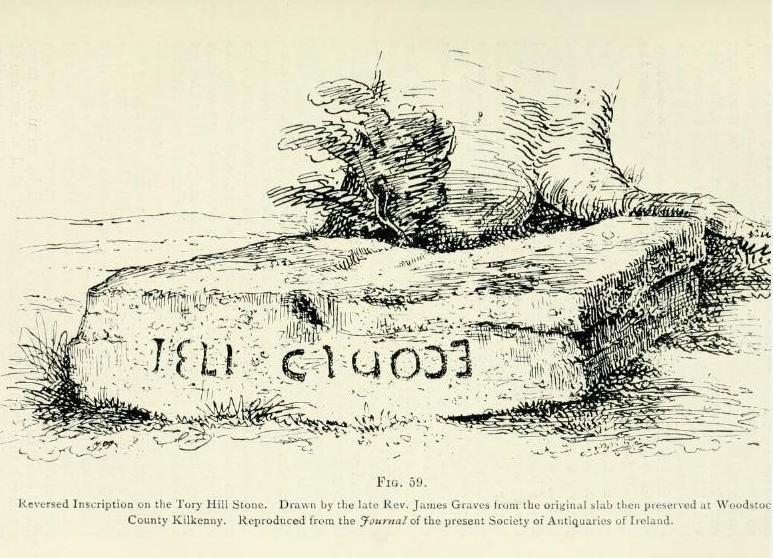

Some years later a group of boys went up the hill and decided to have some fun with a jumping competition: entertainment was evidently lacking in the area. They took the long stone that E. Conic had used and lifted it up and tried to jump over it, making an improvised hurdle. Crucially, they (i) put the stone on top of some other rocks unintentionally creating an ‘altar’; (ii) put it the wrong way up; and (iii) left it there when it was time to go home. This ‘altar’ was first noticed in a publication in 1800, William Tighe’s Statistical Observations relative to the County Kilkenny (622-633). Tighe, in fact, was so impressed by this evidence of contacts with the Mediterranean he took the stone with him when he left. This is his expert analysis.

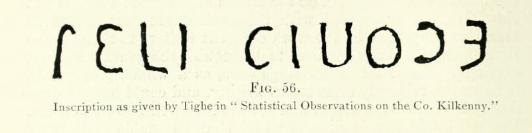

On the summit of Tory hill, called in Irish Sleigh Grian or the hill of the Sun, is a circular space covered with stones; the larger ones have been taken out and rolled down the hill for the use of the country people; there is still one large one near the centre; and there is an appearance of smaller ones, having stood in a circle, at a little distance from the heap, which is above sixty-five yards in circumference: within which, on the east side, is a stone raised on two or three unequal ones, with this inscription, facing the west and the centre of the heap [image of inscription given]

The letters are deeply and well cut, on a hard block of siliceous breccia; they are two inches high, between each is a space of about one inch, and a distance between the words of three inches: in Roman-letters, they would be, BELI DIUOSE. The first letter is one of the most simple forms of the Pelasgic B, in cutting upon a hard stone, the fine strokes may have been omitted: the others are well known. That the Divinity was worshipped in this country under the name of BEL, needs no proof; that the Divinity, was worshipped in the British isles under the name of DIONUSOS, is also recorded: that worship is beautifully described by Dionysius, the Geographer, V. 570, who says, that in the western islands, the wives of the illustrious Ammonians… from the opposite coast, celebrated the worship of DIONUSOS with as great fervor as the Thracians. The stone on which this inscription is cut, is 5 feet 1 inch long, in front; at the back 6 feet 5 inches ; it is 5 feet broad, and 1 foot 4 inches thick. In front appears to have been a sunk place, flagged, the sides diverging; but it is imperfect. The common people pay some respect to this relic.

Beach particularly likes that last sentence and has italicized it in memory of what complete idiots we can be.

Tighe was influential and his theory went through the learned journals and Irish tea-rooms like clap. It was not until 1851 that a scholar James Graves broke the dreadful truth in the Transactions of the Kilkenny Archaeological Society:

But the strangest part of the story remains to be told; when the sketch was reversed it unmistakeably exhibited, not an inscription in honour of any Pelasgian god, but the prosaic words ‘E.CONIC, 1731’ words which however mysterious in appearance, commemorate not a pagan deity, but an humble hewer-out of mill stones.

The reconstruction above is based on a letter from one Dr Donovan (published by Graves) whose grandfather had known Conic well: ‘Ned, the Pelasgian, died about 1745, and little dreamed of his future celebrity’! As one of the locals put it – the entire local population were well aware of the origins of the stone and doubtless enjoyed being paid by Tighe to carry Ned’s rock down the hill – ‘it is astonishing how larned [sic] men can make such fools of themselves!’

Quite.

Other stories about misinterpreted archaeological data or inscriptions: drbeachcombing At yahoo DOT com Beach remembered this classic:

Floodmouse, 31 Mar 2017: There is an 1895 novel by Arthur Machen called “The Three Impostors” with a subplot involving a mysterious black stone discovered in rural England, covered with cryptic engravings of a magical nature. (See the chapter, “Novel of the Black Seal.”) Now that I come to read your blog, it seems clear this was inspired by Tighe’s “discovery,” which had already been outed by Graves in 1851. What I love about the byways of history, is discovering context for the plots of old books and movies that are otherwise inexplicable.